ANN ARBOR, MI—Precautionary practices to prevent infectious agent transmission in hospitals often fail, according to a study looking at 325 patient rooms, including some at a VAMC.

The report in JAMA Internal Medicine pointed out that hospital personnel were beset by “violations, mistakes and slips” when it came to abiding by those protocols.1

The study team, led by researchers from the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the University of Michigan, sought to determine what circumstances led to active failures in transmission-based precautions.

To do that, Sarah L. Krein, PhD, RN, of the VA Center for Clinical Management Research, and colleagues conducted a qualitative study of the patient rooms with precaution signage. They were looking at how effectively healthcare personnel followed protocols, including personal protective equipment (PPE) use, to avoid self-contamination or transmission of pathogens.

“Understanding the types of failures and the context in which failures occur is essential for effectively mitigating the risk of pathogen transmission,” the researchers wrote. “The objective of this study was to identify and characterize failures in transmission-based precautions, including PPE use, by healthcare personnel that could result in self-contamination and transmission during routine hospital care.

Direct observation inside and outside patient rooms on clinical units occurred from March 1, 2016, to Nov. 30, 2016, in the medical and/or surgical units and intensive care units at an academic medical center and the VA hospital, as well as the emergency department of the university hospital.

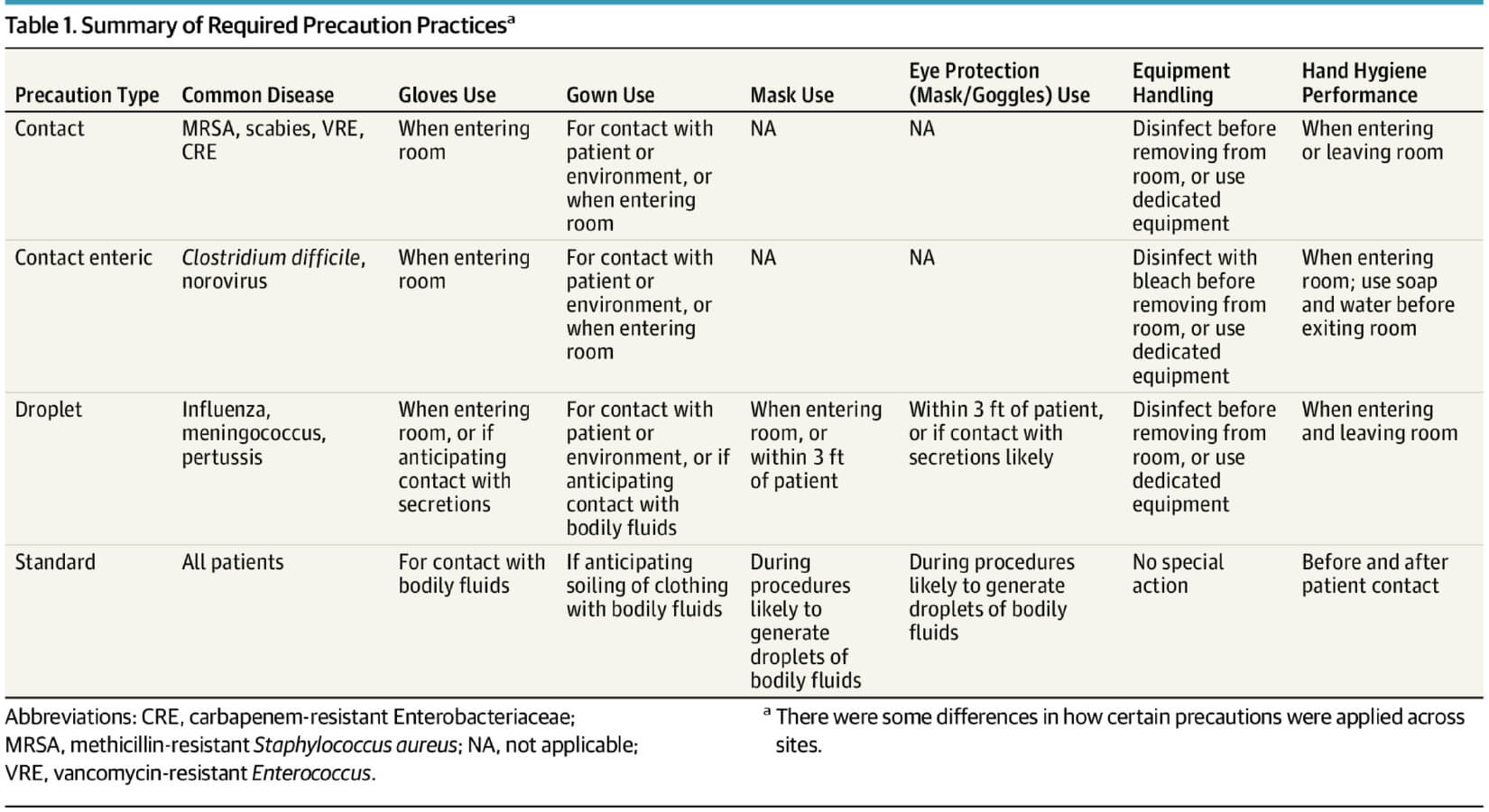

Extensive field notes by trained observers were analyzed on how personnel provided care for patients using precautions for a pathogen transmitted through contact—such as Clostridium difficile or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—or respiratory droplet, such as influenza.

Direct content analysis was used to identify specific occurrences involving potential personnel self-contamination and then further categorized as active failures, such as violations, mistakes or slips, according to the study.

At the first site, 280 observations were completed—196 in medical/surgical units, 64 in intensive care units and 20 in emergency department. At the second site, 45 observations occurred—36 in medical/surgical units and nine in the intensive care unit. Most of the observations, 79.7%, occurred outside patient rooms, with 20.3% occurring inside.

The report documented 283 failures. Those were categorized as the following:

- 102 violations, defined as deviations from safe operating practices or procedures;

- 144 process or procedural mistakes, defined as failures of intention; and

- 37 slips, defined as failure of execution.

Protective Equipment

Violations included entering rooms without some or all recommended PPE, the researchers noted, adding that mistakes frequently occurred during removal of the protective equipment, as well as with challenging logistical situations when suited-up, such as badge-enforced computer logins.

Here are some scenarios actually recorded by the observers:

- In an example of violations without intention of patient contact, a nurse entered a room without using hand hygiene gel or donning PPE and placed water on the patient’s tray table. The nurse then picked up the patient’s call light and turned the light off, exited and foamed hands. (Contact precautions, site 1, emergency department)

- Violations also can occur when patient contact is intended, such as when a physician sanitized hands using the dispenser, then entered the room without donning gloves or gown and touched a patient’s stomach over a gown. The physician then rested an arm on bedside, pulled records out of a white coat pocket, reviewed them, then placed the records back in the pocket before exiting the room and sanitizing hands. (Contact precautions, site 1, non-ICU)

- In other cases, such as a medical emergency, the reasons are more understandable, according to the researchers, such as when a nurse put on gloves, then a mask and grabbed a gown from the stack. When a patient began coughing heavily, the nurse hurried into the room while carrying the gown, put the gown under underarm and completed a patient-related task. With gown under the underarm, gloves and mask on, nurse quickly hurried out of the room. (Droplet precautions, site 2, non-ICU)

- Mistakes, meanwhile, were frequently observed during use of PPE. One example cited was a physician who shook a patient’s hand to conclude a visit. Then, standing in the center of the room, the physician used gloved hands to lift the gown over the head. (Contact enteric precautions, site 2, non-ICU). The physician finally employed a circling motion in the air to twist the gown and gloves into a bundle and put the bundle into the trash. (Contact precautions, site 1, ICU)

- In an example of a slip, a nutritionist stood and leaned on the overbed table with gloved hands. During the conversation, the nutritionist used a gloved hand to push hair behind the ear, then placed a hand back on the table, then used a gloved hand to push eyeglasses higher up on the face. (Contact precautions, site 2, non-ICU)

- Another instance was where a social worker answered a cellphone, pulling it from the back pocket, holding it close to the face and then putting it back into a pocket.

“Slips included touching one’s face or clean areas with contaminated gloves or gowns,” study authors explained. “Each of these active failures has a substantial likelihood of resulting in self-contamination. The circumstances surrounding failures in precaution practices, however, varied not only across but within the different failure types.”

Pointing out that failing short of recommended cautions “commonly occurred,” the study team added, “The factors that contributed to these failures varied widely, suggesting the need for a range of strategies to reduce potential transmission risk during routine hospital care.

“Given the broad array of circumstances contributing to active failures in precaution practices that were identified and categorized, behavioral, organizational, and environmental strategies may be needed to reduce the risk of infection transmission and self-contamination,” they wrote.

The issue has become especially critical with the rise of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia or even emerging drug-resistant organisms. The answer includes precautions such as hand hygiene and the use of PPE, the study noted, but also decried poor compliance with PPE use.

“Our findings are consistent with the issues involving appropriate PPE use identified by other studies. Similarly, our results suggest that previously identified factors, including knowledge and risk perceptions, likely contribute to the observed failures,” study authors concluded. “Improving the use of PPE often requires skills training and correcting knowledge deficits, but our in-depth assessment broadens existing knowledge, including potential targets, contributing factors and strategies for intervention and improvement.”

They called for several possible solutions, including PPE gown redesign to improve functionality; “environmental cues to prompt appropriate actions, such as proper doffing sequence; changes to the built environment to ensure sufficient space and access to supplies during care delivery; and identifying more effective strategies for dealing with specific challenges, such as in-room computer log-ins and cognitive load issues.”

1. Krein SL, Mayer J, Harrod M, et al. Identification and Characterization of Failures in Infectious Agent Transmission Precaution Practices in Hospitals; A Qualitative Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1051–1057. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1898