Mortality Reduced more than 44% During Iraq, Afghanistan Conflicts

SAN ANTONIO—The ability of military medicine to constantly innovate in saving the lives of wounded warriors reduced mortality 44.2% during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, according to a new study.

Credited with increasing survival rates were increased use of tourniquets, blood transfusions and reduced time to surgical treatment (i.e., within an hour). In fact, the study led by researchers from the DoD Joint Trauma System at Joint Base San Antonio–Fort Sam Houston and the University of Texas at San Antonio found that, from October 2001 through December 2017, survival increased threefold among the most critically injured. That was the case even though many had severe multiple-trauma injuries, most of which included head, chest and extremity injuries caused by explosive mechanisms.

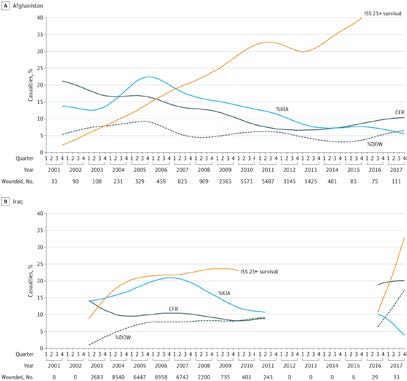

By the end of 2017, the overall case-fatality rate in Afghanistan was 8.6%, down from 20.0% in October 2001; in Iraq, it was 10.1%, down from 20.4% in March 2003, according to the report in JAMA Surgery.1

During the same period, survival with an Injury Severity Score of 25 to 75 (critical) increased from 8.9% to 32.9% in Iraq and from 2.2% to 39.9% in Afghanistan. Study authors pointed out that critically injured casualties accounted for 16.2% of casualties and 90.1% of deaths overall in Afghanistan and 16.4% of casualties and 90.5% of deaths in Iraq.

“The Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts have the lowest case-fatality rates in U.S. history, but the purpose of this study was to provide the most comprehensive assessment of the trauma system by compiling the most complete data on the conflicts and analyzing multiple interventions and policy changes simultaneously,” explained lead author Jeffrey Howard, PhD. “We used novel analytical methods to simulate what mortality would have been without key interventions.”

Source: JAMA Surg. Published online March 27, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0151

Data for combat casualties were compiled from four DoD databases: the Defense Manpower Data Center Defense Casualty Analysis System, the Joint Trauma System Department of Defense Trauma Registry, the Armed Forces Medical Examiner Tracking System and the U.S. Central Command Commander’s Daily Secretary of Defense Casualty Reports. Researchers compared casualty status—alive, killed in action or died of wounds, the case-fatality rate and the contribution of different interventions—to changes in the CFR.

Their results underscored that survival wasn’t improved because the injuries were less severe but because emergency response was better.

Here are some of the key findings:

- Injuries caused by explosives increased 26 % in Afghanistan and 14% in Iraq.

- Head injuries increased 96% in Afghanistan and 150% in Iraq.

- Yet, survival for critically injured casualties increased from 2.2% to 39.9% in Afghanistan and from 8.9% to 32.9% in Iraq.

The three key interventions— increased use of tourniquets, increased use of blood transfusion, and more rapid hospital transport times—were credited with about 44% of the reduction in mortality, especially in Afghanistan.

“Given that the primary cause of death in combat trauma is hemorrhage,38 these findings are not surprising,” study authors wrote. “The key lesson from 16 years of conflict is that military trauma system advancements may be associated with increased survival, echoing historical themes of continued improvements to hemorrhage control and blood replacement and reducing time to treatment.”

Researchers suggested those efforts saved more than 1,600 lives. Without the innovations in intervention and policy, on the other hand, an estimated 3,600 additional deaths would have occurred between 2001 and 2017, they posited.

Explosive Devices

The study pointed out that the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq were noted for the increased use of explosive devices as primary mechanisms of injury. Explosive injuries were associated with a 34.1% increase in odds of KIA death in Afghanistan and a 114% increase in odds of KIA death, as well as a 72% increase in odds of DOW death in Iraq “The shift to a predominantly explosive injury mechanism was accompanied by a commensurate shift in wounding pattern and toward complex multiple-trauma injuries involving more than one body region,” researchers explained.

The report also discussed how the military trauma system responded to changes in MOI and injury patterns by introducing new or improved devices to control bleeding. Greater use of tourniquets appeared to lower death rates from traumatic extremity amputation or vascular injury. The study authors noted that, early in the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts, traumatic amputation was more life-threatening, because tourniquets were rarely used and bleeding control was not rapid enough.

“Although the tourniquet concept is centuries old, improvements in tourniquet effectiveness, ease of use, and increased availability at the point of injury developed during current conflicts helped to propagate their use and improve casualty survival.,” they recounted.

Increased use of blood transfusion was another important factor leading to mortality reduction, more so in Afghanistan than Iraq., the study added, pointing out, “Research conducted from 2003 to 2008 led to advances in component therapy and safer use of fresh whole blood. In turn, this advance benefited more casualties in Afghanistan as fighting continued and intensified there, whereas it diminished in Iraq.”

Interestingly, the article described how pre-hospital transport times were consistently more rapid in Iraq, where more than two-thirds of all casualties and three-fourths of critical casualties were transported from the point of injury to surgical capability within 60 minutes, than in Afghanistan. That changed in June 2009 when Secretary of Defense Robert Gates mandated pre-hospital transport times be reduced to 60 minutes or less. Before that, percentages of casualties transported within 60 minutes ranged from 17.5% to 42.7%, but, afterward, the percentage of casualties meeting the 60-minute target increased rapidly to levels comparable to those in Iraq.

“Our findings suggest that, similar to previous reports, more rapid transport was associated with reduced odds of KIA death in Afghanistan. The data also suggest that more rapid transport may have been associated with a small increase in odds of DOW death in Afghanistan but was offset by reductions in KIA and reduction in odds of DOW from tourniquet and blood transfusion practices,” the authors explained.

In an accompanying editorial, Brian Gavitt, MD, MPH, of the Center for Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills–Cincinnati, US Air Force School for Aerospace Medicine, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, in Dayton, OH, and Timothy A. Pritts, MD, PhD, a surgeon at the University of Cincinnati, said the Joint Trauma System “has proven extraordinarily effective at continually implementing changes to improve both prehospital and in-hospital care for wounded warriors.”2

Gavitt and Pritts, added, “We can honor those who serve in our armed forces by working to eliminate potentially preventable battlefield deaths and sustaining a military trauma system worthy of those it treats. The authors of the present study should be congratulated for their work. The knowledge gained about the contributions of this critical combination of lifesaving interventions should be implemented in civilian and military trauma care so that hard-earned lessons learned will not soon become lessons forgotten.”

Howard agreed, adding, “Many of the lessons from the current war had actually been learned before in prior wars. My colleagues and I are trying to propagate these lessons throughout the scientific and medical literature to inform military trauma care policies for the future.”

1. Howard JT, Kotwal RS, Turner CA, Janak JC, Mazuchowski EL, Butler FK, Stockinger ZT, Holcomb BR, Bono RC, Smith DJ. Use of Combat Casualty Care Data to Assess the US Military Trauma System During the Afghanistan and Iraq Conflicts, 2001-2017. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0151. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30916730.

2. Gavitt B, Pritts TA. Hard-Earned Lifesaving Lessons From the Combat Zone. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0152. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30916739.