SEATTLE — The treatment options for prostate cancer are rapidly evolving, in no small part as a result of the VA’s expanded commitment to clinical trials and precision medicine.

Two developments have driven dramatic changes in the past two years—and promise to bring more in the coming months. The first involves the use and timing of androgen receptor targeting therapies; the second, the discovery of high rates of DNA repair defects in prostate cancer tumors.

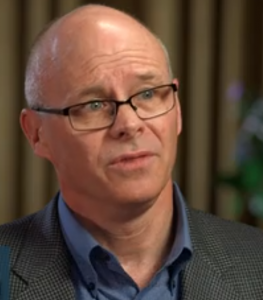

“We’ve seen a number of new approvals and clinical study results which have been quite compelling, all targeting androgen receptors,” said Bruce Montgomery, MD, co-leader of the Prostate Cancer Foundation-VA precision medicine initiative, medical oncologist at the VA Puget Sound and clinical director of genitourinary medical oncology at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“We knew it was important, but all these being positive reemphasizes the importance of androgen receptor inhibitors even early in the disease, when they can be used with radiation, through to castration resistant prostate cancer,” he told U.S. Medicine.

For decades androgen deprivation therapy, or hormone therapy, has formed the standard first-line treatment for men with newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer. Depending on the drug used, ADT suppresses testosterone production or blocks activation of the androgen receptor. While 90% of patients initially respond to the therapy, within a few years nearly all will develop castration-resistant prostate cancer and experience disease progression despite continued testosterone suppression.

The discovery by Montgomery and colleagues that prostate cancer tumors continue to produce androgens even during active hormonal therapy led to the development and ultimate approval of two drugs that closed this back door: the nonsteroidal anti-androgen abiraterone administered with prednisone and the androgen receptor inhibitor enzalutamide.

Until recently, however, they have not been used before ADT failed.

“Historically, we’ve used androgen deprivation until the cancer became resistant, then moved onto other drugs,” Montgomery explained. “Now the studies show a survival advantage for hormone therapy plus androgen-receptor drugs” at earlier stages.

“The most compelling data is for men with high-risk metastatic hormone-responsive prostate cancer. Using either chemotherapy (docetaxel) or abiraterone early, when metastasis first develops, along with androgen suppression provided a survival advantage of 20 to 24 months. Usually, we’re talking about a difference of a couple of months with new therapies,” Montgomery noted.

The LATITUDE study demonstrated abiraterone with prednisone plus ADT reduced the risk of death 33% in men with newly diagnosed metastatic hormone-response prostate cancer after more than 51 months of follow-up.1 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration expanded abiraterone’s approval to include this indication in February.

“The two most recent studies show that enzalutamide and apalutamide showed very similar survival advantages for new metastatic hormone-responsive prostate cancer. Both are very likely to be approved in this setting,” Montgomery added.

Several of drugs that act on the androgen receptor pathway gained FDA approval in another setting in recent months.

Three studies published in rapid succession last year in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated that adding an androgen-receptor inhibitor to ADT substantially extended metastasis-free survival compared to ADT alone in patients with non-metastatic CRPC whose prostate-specific antigen was doubling in less than 10 months.

The first study, co-authored by Julie N. Graff, MD, of the VA Portland Health Care System and Knight Cancer Institute at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, OR., found that patients with nonmetastatic CRPC who received apalutamide plus ADT had median metastasis-free survival of 40.5 months compared with 16.2 months in those who received placebo plus ADT.2 The other two studies showed a similar benefit: 36.6 months for enzalutamide vs. 14.7 months for placebo and 40.4 months for darolutamide vs. 18.4 months for placebo.3,4

Apalutamide gained U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for this indication in February 2018, while the FDA expanded enzalutamide’s approval to include nonmetastatic CRPC in July 2018. Darolutamide was approved in July of this year for the same indication.

Nonmetastatic may be a bit of a misnomer in these cases, Montgomery noted. “These are not cases necessarily of cancer that has not spread; it may be that the volume is just not large enough to be seen yet.”

Over a 10-year period, about 27,000 veterans receiving care through the VA fell into the nonmetastatic CRPC category at some point, according to a study presented at the American Urological Association 2019 Annual Meeting.5

While the three new drugs extend time to development of metastases, the studies have not yet demonstrated that they provide a survival benefit to patients with nonmetastatic CRPC, Montgomery noted.

In that context, in particular, “we need to talk about financial toxicity. It’s about $10,000 per month out of pocket outside the VA. While the VA’s cost is not quite that high, it’s still quite expensive, given that we are treating a very large number of patients. How do we sustain our ability to do that and treat patients with every other malignancy, as well?”

The cost equation may be a little easier for patients with metastatic CRPC as docetaxel has long been off patent and abiraterone is now available in a lower-cost formulation from Sun Pharmaceutical. A generic version produced by Argentum Pharmaceuticals is expected on the market by 2021.

Continue Reading: