Is the Answer Specific Drugs, Not Tight Glycemic Control?

At one point, intensive glycemic control was seen as a magic bullet to keep Type 2 diabetes patients from developing cardiovascular disease. That approach faded, however, when VA research cautioned that any benefits of intensive therapy must be weighed against adverse effects such as hypoglycemia and weight gain. Now the focus has shifted to better medication selection, with guidelines suggesting that, for Type 2 diabetes patients who have cardiovascular disease or are at high risk for it, therapy including an SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 RA should be considered as optimal treatment.

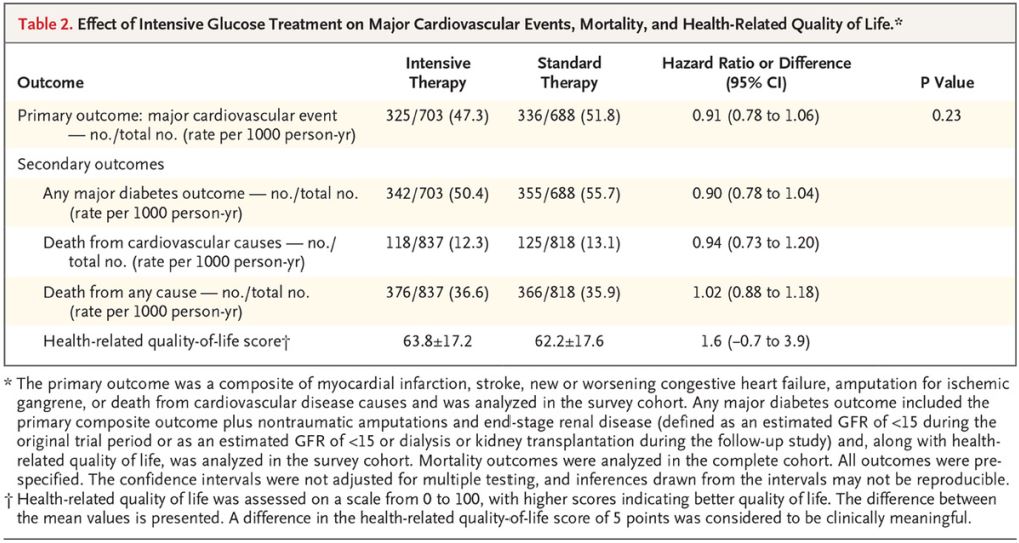

Effect of Intensive Glucose Treatment on Major Cardiovascular Events, Mortality, and Health-Related Quality of Life.* Click to Enlarge

PHOENIX, Arizona — The VA’s battle to protect veterans with Type 2 diabetes from cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality has gone on for decades.

Its landmark VA Diabetes Trial, which began in 2000, was a randomized trial of intensive glycemic control in veterans with advanced Type 2 diabetes. The 1,791 participants from 20 VAMCs were at relatively high risk for cardiovascular disease, including heart attack and stroke, with many of them already having been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease.

VA researchers sought to determine whether intensive glycemic control would reduce those risks and found the long-term effects to be limited. Now, it looks like as if the focus is less on glycemic control and more on specific agents that appear to improve cardiovascular outcomes, especially glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

The issue is especially critical at the VA, where nearly one-fourth of the patients have diabetes, primarily Type 2. Those veterans also are estimated to have two to four times the risk of heart disease.

A 15-year VADT follow-up published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine noted that “trials involving patients with advanced Type 2 diabetes (such as ACCORD [Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes], ADVANCE [Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation], and our own VADT [Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial]) showed that improved glucose control over a median of 3 to 6 years provided modest and nonsignificant reductions in the incidence of cardiovascular events and did not reduce cardiovascular disease–related mortality or total mortality.”

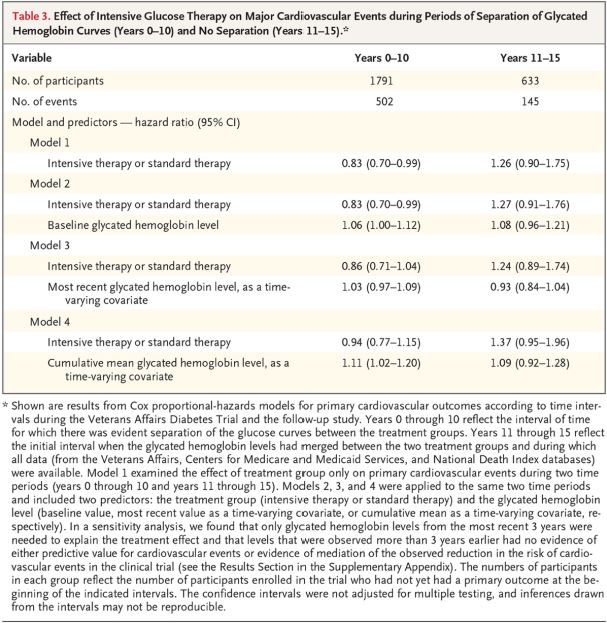

Effect of Intensive Glucose Therapy on Major Cardiovascular Events during Periods of Separation of Glycated Hemoglobin Curves (Years 0–10) and No Separation (Years 11–15).* Click to Enlarge

While the 10-year follow-up of the VADT showed an emerging benefit for CVD reduction from the original intensive glucose-lowering, the longer-term follow-up indicated no significant drop, on average, in heart attacks or stroke.

In 15-year findings from VADT, researchers found that nearly six years of aggressive lowering of blood sugar levels resulted in a non-significant 12% decline in cardiovascular events—a composite of heart attack, stroke, cardiovascular death, congestive heart failure and amputation from gangrene—when compared with standard therapy. In addition, no differences in all-cause death were documented, and a long-term trend for reduced renal events was insignificant.1

“This points out how difficult it sometimes is to maintain tight glycemic control,” Nicholas Emanuele, MD, of the Edward Hines Jr. VAMC in Hines, IL, one of the three lead investigators on the VADT follow-up. “Outside the rigors of a precise protocol like the VADT, it’s easy for patients to let glucose control slip. It’s a tough disease in many ways.

“Remember, there was a significant cardiovascular benefit of good sugar control at 10 years,” he pointed out. “So, one interpretation of this is that good glycemic control is beneficial. But it must be sustained, or the benefit is lost.”

The study also cautioned that any benefits of intensive therapy must be weighed against adverse effects such as hypoglycemia and weight gain.

Looking at the alternative approach, the authors explained, “Studies showing major reductions in the risk of cardiovascular outcomes with diabetes agents, such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, that only achieve modest improvements in glycemic control highlight the importance of also considering nonglycemic approaches to reducing the risks of cardiovascular events and death among high-risk patients with Type 2 diabetes.”

Indeed, that appears to be the new direction in 2020 guidelines from the American Diabetes Association. The document recommended that, for Type 2 diabetes patients who have cardiovascular disease or are at high risk for it, an SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 RA should be considered as optimal treatment—and that the decision should be made independent of hemoglobin A1c levels.

In the past, the ADA generally hadn’t weighed in much of what medication should be added to metformin as a second agent in patients with Type 2 diabetes.

That stance generally continued in the 2020 Standards of Medical Care, published in Diabetes Care, with authors advising, “The choice of medication added to metformin is based on the clinical characteristics of the patient and their preferences.” 2

For the first time, however, the ADA made a strong recommendation for what drugs should be used in diabetes patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or at high risk for it. The panel urge strong consideration for the use of sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

“For patients with established ASCVD or indicators of high ASCVD risk (such as patients ≥55 years of age with coronary, carotid, or lower-extremity artery stenosis >50% or left ventricular hypertrophy), established kidney disease, or heart failure, an SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 RA with demonstrated CVD benefit is recommended as part of the glucose-lowering regimen independent of A1c and in consideration of patient-specific factors,” the ADA wrote in the revised statement.

The standards pointed out that, despite numerous trials comparing dual therapy with metformin alone, there is little evidence to support one combination over another for patients without ASCVD or significant risk factors.

“A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis suggests that each new class of noninsulin agents added to initial therapy with metformin generally lowers A1C approximately 0.7–1.0%,” according to the document. “if the A1c target is not achieved after approximately three months, metformin can be combined with any one of the preferred six treatment options: sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 RA, or basal insulin; the choice of which agent to add is based on drug-specific effects and patient factors.”

The 2020 ADA guidance went on to state, “Although most patients prefer oral medications to drugs that need to be injected, the eventual need for the greater potency of injectable medications is common, particularly in people with a longer duration of diabetes. The addition of basal insulin, either human NPH or one of the long-acting insulin analogs, to oral agent regimens is a well-established approach that is effective for many patients. In addition, recent evidence supports the utility of GLP-1 RAs in patients not reaching glycemic targets with use of non-GLP-1 RA oral agent regimens.”

It pointed out that new options are available, however. “While most GLP-1 RA products are injectable, an oral formulation of semaglutide is now commercially available. In trials comparing the addition of an injectable GLP-1 RAs or insulin in patients needing further glucose lowering, the efficacy of the two treatments was similar. However, GLP-1 RAs in these trials had a lower risk of hypoglycemia and beneficial effects on body weight compared with insulin, albeit with greater gastrointestinal side effects. Thus, trial results support injectable GLP-1 RAs as the preferred option for patients requiring the potency of an injectable therapy for glucose control. However, high costs and tolerability issues are important barriers to the use of GLP-1 RAs.”

In September 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced its approval of semaglutide oral tables, marketed as Rybelsus, to improve control of blood sugar in adult patients with Type 2 diabetes, along with diet and exercise. Rybelsus was the first GLP-1 receptor protein treatment approved for use in the United States that does not need to be injected.

“Patients want effective treatment options for diabetes that are as minimally intrusive on their lives as possible, and the FDA welcomes the advancement of new therapeutic options that can make it easier for patients to control their condition,” explained Lisa Yanoff, MD, acting director of the Division of Metabolism and Endocrinology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Before this approval, patients did not have an oral GLP1 option to treat their Type 2 diabetes, and now patients will have a new option for treating Type 2 diabetes without injections.”

A review from authors at the Richmond, VA, VAMC and Virginia Commonwealth University Health System recently pointed out that “pathophysiological and clinical associations between diabetes and cardiovascular disease have been the subject of multiple studies, most recently culminating in large trials of several new anti-glycemic agents being found to confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction.”

In an article in Expert Reviews of Cardiovascular Therapy, the authors emphasized that better understanding cardiovascular benefits of anti-glycemic medications could potentially reduce the morbidity and mortality of both diseases at once.3

“The treatment of patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease is rapidly advancing. In particular, the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have demonstrated cardiovascular benefit by reducing major adverse cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality,” according to the report. “Future directions of the treatment of Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease will focus on targeting and preventing diabetic cardiomyopathy and further defining the role of SGLT2 inhibitors and of GLP-1 receptor agonists in additional patient populations.”

- Reaven PD, Emanuele NV, Wiitala WL, et al. Intensive Glucose Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes—15-Year Follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(23):2215‐2224. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806802

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S14‐S31. doi:10.2337/dc20-S002

- Choxi R, Roy S, Stamatouli A, Mayer SB, Jovin IS. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: focus on the effect of antihyperglycemic treatments on cardiovascular outcomes [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 24]. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2020;1‐13. doi:10.1080/14779072.2020.1756778