FORSAN, TX — By rolling out the Whole Health System, the VA expects to transform care for veterans and could establish the agency as the national leader in a fundamentally different, truly integrated approach to healthcare.

The Whole Health program asks alternative questions of patients. “Traditional care with its disease focus asks, ‘What’s the matter?’ We start from a different place and ask veterans, ‘What matters to you?’” said Lauri Phillips, Associate Director Whole Health System Development, Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation.

That makes a huge difference in the topics discussed, recommendations made, and—perhaps most significantly—in veteran engagement in their healthcare and overall wellbeing, she told U.S. Medicine.

“While a clinician may have a goal of improving a patient’s blood sugar of blood pressure or fill in the blank, improving a particular problem may not resonate with a specific person,” Phillips noted. For many veterans, changing the numbers on lab results are the physician’s priorities, not theirs.

“For example, we had a woman with a variety of issues—weight, blood pressure, blood sugar,” Phillips said. “What she wanted was to be able to bend over to tie her shoes without struggling. Once we focused on that, the other issues naturally resolved.”

Each veteran has different goals and priorities. To really address the whole person, the VA has learned providers and others need to look less at the medical issues themselves and more at how those impact the veteran’s life. “It’s a matter of asking, ‘What do you want health for?’” Phillips said.

Self-exploration

Shifting the conversation requires changing veteran’s expectations and understanding of their healthcare as much as training providers to take a different approach. “The process starts with self-exploration,” Phillips noted. “We found the best way to empower them is to take them through a personal health inventory that looks at what different areas in their lives would they want to engage in improving.”

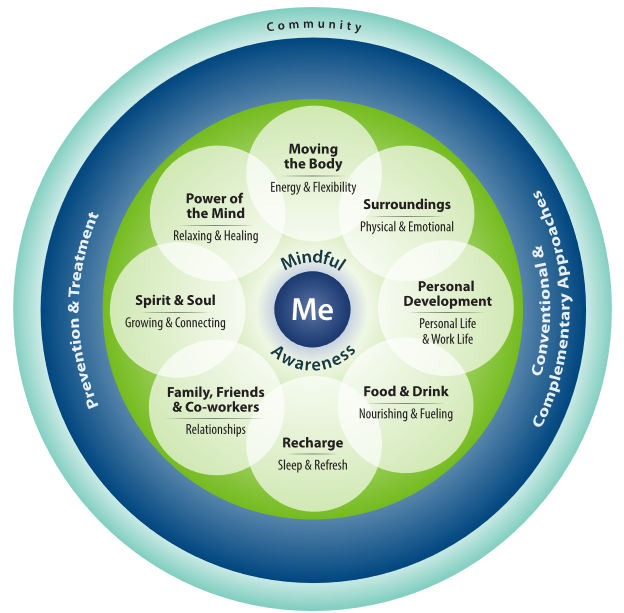

Those discussions walk veterans through the “Circle of Health,” a visual tool that literally puts the patient in the center of the image surrounded by eight intertwined areas of self-care that all impact wellbeing. Those include nutrition, movement, rest, relationships, spirituality, mindfulness, surroundings, and personal development.

“Out from there, are the things we can do as clinicians. That’s a smaller piece than the self-care area, because we all have so much ability to affect our own health,” Phillips added. Walking through the circle helps veterans determine what they want to be able to do and how their wellbeing affects that. Once they gain awareness of the connection between their health and their life priorities, they have motivation to take steps to improve all the dimensions of their overall wellbeing.

“We can connect them with a plethora of resources for self-care, such as chaplains, nutrition professionals, and other providers, but until you engage with them and help them determine what they want health for, they may not see a purpose in accessing all the wonderful information and services that are out there,” explained Phillips.

Peer Facilitators

The VA has trained veterans as Whole Health peer facilitators to help other veterans through this process. “We have found that veteran peers are oftentimes more effective in having conversations about health than clinicians,” said Phillips. “Sometimes it’s good to get the clinical perspective out of the way and have a peer-to-peer conversation. Veterans have a strong community and shared experiences. They can connect quickly and deeply with veteran peers. That’s not to say that clinicians don’t have those conversations, but they may not have the time to explore as deeply and veterans may not feel as comfortable as with another peer in some cases.”

Once a veteran has gained an understanding of their goals and how their health and behaviors affect what they want to accomplish, they can move on to work with a health coach if they want. “Veteran peers are not trained to help veterans reach their goals,” just to identify them, Phillips noted. “Health coaches can work in a deeper way to reach goals and we’re seeing a lot of anecdotal effectiveness with both veterans and clinicians appreciating the help.”

Health coaches may work with groups or one-on-one with a veteran or veterans may choose to work on specific issues with a provider. The VA has also leveraged its telehealth system to make Whole Health groups available to veterans who cannot easily get to a facility for workshops or coaching sessions, but still can benefit from both the trained facilitation and the motivation that comes from establishing a personal connection with others on the same journey or a coach who is cheering them on.

The VA has started to present the Whole Health program to transitioning service members to begin the conversation about goals and health. As they transition into veteran status, the VA offers an introduction to Whole Health session and also provides information through its website.

Once veterans develop a plan through the Whole Health discussion, “they can take the plan with them as they engage with clinicians, primary care providers, nutritionist, physical therapist. Each of those providers can see what the veteran’s goals are and how they want to achieve them. We hope that the plan is an integrator to help them achieve their goal,” Phillips said.

The VA is still adapting systems and reporting measures to capture Whole Health encounters and achievements. “It’s all new,” Phillips noted. “It’s not something anyone has done in the private sector, so we’re trying to figure out how to document it all in the medical record, but it’s been really encouraging anecdotally.”