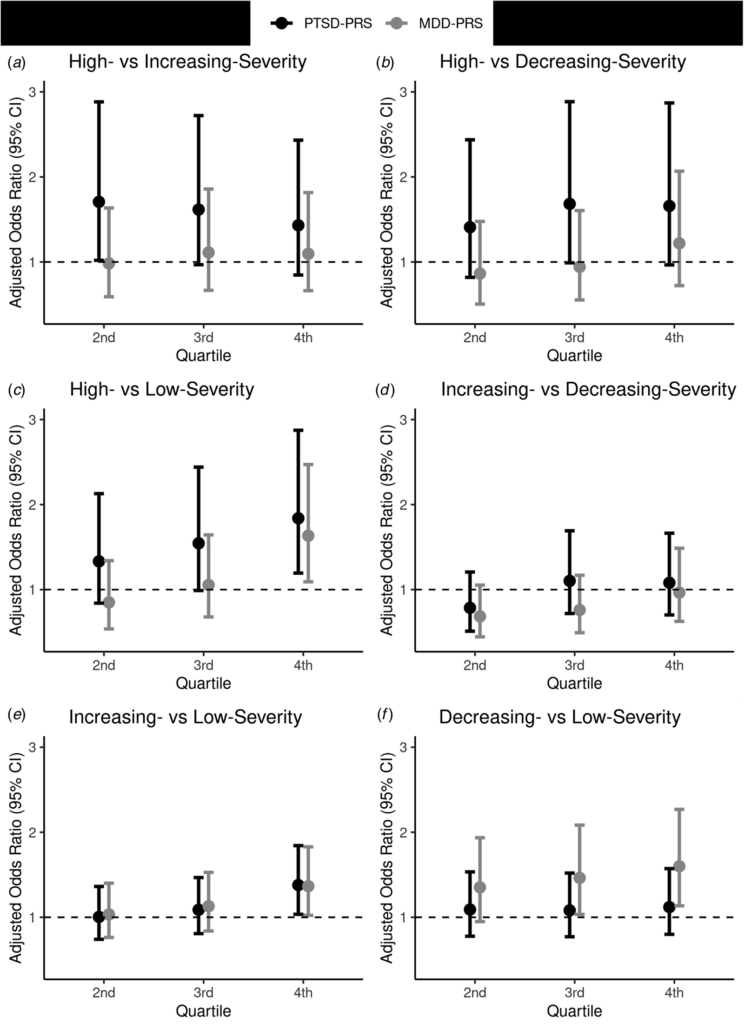

Click to Enlarge: Plot of AORs for each PRS quartile relative to the first quartile. Source: Cambridge Core

SAN DIEGO — The risk for specific soldiers to have severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appears to far predate their deployment. In fact, some military personnel are born with it, according to a new study.

At least some of the risk factors are genetic, according to a new study led by the VA San Diego Healthcare System, the University of California San Diego and colleagues.

The report in the journal Psychological Medicine suggested that Identification of genetic risk factors could help in the prevention and treatment of PTSD. A study evaluated the associations of polygenic risk scores (PRS) with patterns of PTSD following combat deployment.

Genomic data and ratings of PTSD were provided by U.S. Army soldiers of European ancestry before and after deployment to Afghanistan in 2012. Researchers modeled PTSD trajectories among 4,353 participants who provided complete post-deployment data.

The investigative team used models to test for independent associations between PTSD course major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia, neuroticism, alcohol-use disorder and suicide attempt. The study was controlled for age, sex, ancestry and exposure to potentially traumatic events; it also was weighted to account for uncertainty in trajectory classification and missing data.

Researchers classified participants as having PTSD trajectories of:

- low-severity (77.2%),

- increasing-severity (10.5%),

- decreasing-severity (8.0%), and

- high-severity (4.3%).

“Standardized PTSD-PRS and MDD-PRS were associated with greater odds of membership in the high-severity vs. low-severity trajectory [adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals, 1.23 (1.06-1.43) and 1.18 (1.02-1.37), respectively] and the increasing-severity vs. low-severity trajectory [1.12 (1.01-1.25) and 1.16 (1.04-1.28), respectively],” they determined. “Additionally, MDD-PRS was associated with greater odds of membership in the decreasing-severity vs. low-severity trajectory [1.16 (1.03-1.31)]. No other associations were statistically significant.”

The study concluded that higher polygenic risk for PTSD or MDD is associated with more severe PTSD trajectories following combat deployment. “PRS may help stratify at-risk individuals, enabling more precise targeting of treatment and prevention programs,” the authors advised.

Background information in the article noted that traumatic events affect most adults during their lifetimes, though responses can vary greatly. “The modal response to trauma is resilience, wherein only minimal or transient symptoms emerge following the stressful event,” the authors pointed out. “On the other end of the severity spectrum is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition characterized by re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition or mood, and hypervigilance that persists for 3 months or more.”

The researchers noted that “about 5-10% of trauma-exposed individuals develop PTSD, with many others suffering from acute stress reactions lasting less than 3 months, or from clinically significant symptoms that fail to meet full PTSD diagnostic criteria.”

The study explained that evidence from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) suggests multiple risk loci in the etiology of PTSD, and that the effects can be described as polygenic risk scores (PRS).

Disproportionately Impacted

“Early suggestions that PRS hold promise as a risk stratification tool are encouraging but require replication and extension to other populations and settings,” the authors wrote. “Military personnel are disproportionately impacted by PTSD, due in part to the nature and frequency of trauma exposure within this population. The Pre- / Post-Deployment Study (PPDS) of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) provides an opportunity to investigate whether PRS are associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms in combat-deployed military personnel.”

They added that their study included multiple outcome assessments during the period following potential trauma exposure—approximately 1, 3 and 9 months after return from deployment.

“These findings raise important questions beyond the basic issue of whether PRS are associated with more severe post-traumatic stress symptoms or PTSD diagnosis,” the researchers pointed out. “These questions include whether PRS may help identify at-risk individuals who would be difficult to detect using other clinical tools (e.g., those with a delayed onset of symptoms) and whether PRS may help differentiate individuals vulnerable to short-term post-traumatic stress symptoms from those at risk of chronic symptoms. Evidence of either of these capabilities would increase the potential value of PRS for targeted prevention efforts.”

- Campbell-Sills L, Papini S, Norman SB, Choi KW, He F, Sun X, Kessler RC, Ursano RJ, Jain S, Stein MB. Associations of polygenic risk scores with posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories following combat deployment. Psychol Med. 2023 Mar 6:1-10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291723000211. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36876647.