Findings Call Into Question the Push for More Outside Veteran Care

Click To Enlarge:

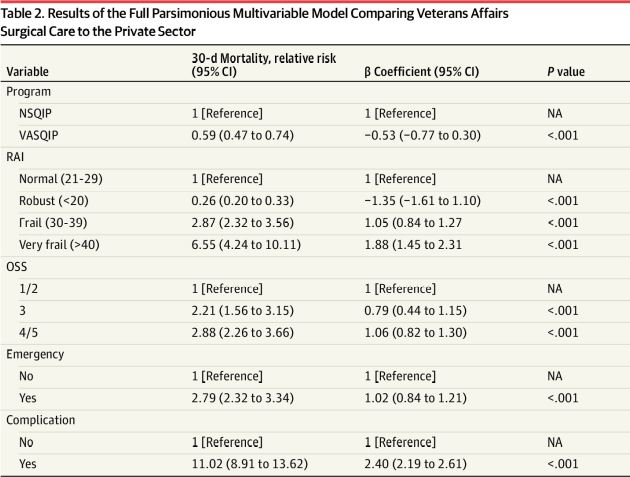

Abbreviations: NA – Not Applicable; NSQIP – National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; OSS – Operative Stress Score; RAI – Risk Analysis Index; VASQIP – Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program

MENLO PARK, CA — Perioperative outcomes at the VHA are consistently better than those in private sector hospitals, according to a new study.

The report in JAMA Surgery pointed out that the national cohort study looking at more than four million surgical procedures found that surgical care provided in the VA healthcare system was associated with lower perioperative mortality and decreased failure to rescue.1

Researchers led by Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, CA, and the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System in Menlo Park, CA, didn’t shy from addressing the elephant in the room whenever VHA care is found superior to that provided in the community. “In light of recent legislation facilitating veterans’ ability to receive non-VA surgical care and given the unique needs and composition of the veteran population, health policy decisions and budgetary appropriations should consider the association between care setting and perioperative outcomes for veterans receiving care within the Veterans Health Administration,” the authors advised.

The article noted that the VA Mission Act, signed into law in 2018, facilitates veterans’ ability to receive surgical care outside of the VHA. “However, contemporary data comparing the quality and safety of VA and non-VA surgical care are lacking,” the study team wrote. That’s why they sought to compare perioperative outcomes among veterans treated in VA hospitals with patients treated in private-sector hospitals.

The cohort study involved eight noncardiac specialties in the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP) and American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) from Jan. 1, 2015, through Dec. 31, 2018. VA vs. private sector care settings and 30-day mortality were evaluated using modeling. Defined as the primary outcome was 30-day postoperative mortality, with the secondary outcome being failure to rescue, defined as a postoperative death after a complication.

Of the 3.9 million surgeries—3.2 million from VASQIP and 736,477 from NSQIP—92.1% patients in VASQIP were male compared to 47.2% in NSQIP (mean difference, -0.449 [95% CI, -0.450 to -0.448]; P <0.001). Another difference was that 60.0% of the participants in VASQIP were frail or very frail vs. 21.3% in NSQIP (mean difference, -0.387 [95% CI, -0.388 to -0.386]; P < .001).

Results indicated that, overall, rates of 30-day mortality, complications, and failure to rescue were 0.8%, 9.5% and 4.7%, respectively, in NSQIP and 1.1%, 17.1% and 6.7%, respectively, in VASQIP (differences in proportions, -0.003 [95% CI, -0.003 to -0.002]; -0.076 [95% CI, -0.077 to -0.075]; 0.020 [95% CI, 0.018-0.021], respectively; P < 0.001).

“Compared with private sector care, VA surgical care was associated with a lower risk of perioperative death (adjusted relative risk, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.47-0.75]; P < 0.001),” the researchers explained. “This finding was robust in multiple sensitivity analyses performed, including among patients who were frail and nonfrail, with or without complications and undergoing low and high physiologic stress procedures. These findings also were consistent when year was included as a covariate and in nonparsimonious modeling for patient-level factors. Compared with private sector care, VA surgical care was also associated with a lower risk of failure to rescue (adjusted relative risk, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.44-0.68]). An unmeasured confounder (present disproportionately in NSQIP data) would require a relative risk of 2.78 [95% CI, 2.04-3.68] to obviate the main finding.”

The authors emphasized that lower perioperative mortality and decreased failure to rescue occurred with VA surgical procedures, even though veterans had higher-risk characteristics. “Given the unique needs and composition of the veteran population, health policy decisions and budgetary appropriations should reflect these important differences,” they asserted.

Also participating in the study were researchers from VAMCs in Houston, Pittsburgh, Omaha, NE, and San Antonio.

In a linked commentary, authors from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School emphasized that legislation grew out of concerns about access to care at the VA but pointed out, “better access to health care does not necessarily result in improved outcomes. By showing that veterans have lower 30-day postoperative mortality in VA hospitals compared with private sector hospitals, [the authors] demonstrate the important distinction between quality of care and timeliness of access.”2

Background information in the report described how, over the past decade, eligibility for veterans to receive nonurgent care outside the VA system has been loosened. At the same time, according the article, “numerous studies comparing the quality of preventive services, primary care, mental health care, oncology, posttransplant care, and surgical specialties suggest VHA performs better, comparable with, or less variably relative to the private sector. Because surgical care is both high risk and costly, understanding the most appropriate surgical care setting for veterans is critical for informing current and future health policy decisions and budget appropriations.”

Best Equipped to Care for Veterans

Researchers pointed to two key conclusions from their study: That VA surgical care is associated with a lower risk of perioperative death—“a finding that was robust to varying assumptions about the data”—and that the results were consistent among patients who experienced complications, as shown by the lower failure to rescue data. “Taken together, this suggests VA hospitals may be best equipped to care for the unique perioperative needs and risk profiles of veterans,” they argued.

Part of the reason for the good surgical quality of care at the VHA is that VASQIP has been credited with substantial reductions in postoperative morbidity and mortality across VA hospitals and was used as a model for NSQIP in the private sector, according to the authors.

Despite limitations of the study—primarily that only certain Americans can quality for VA care—the authors said their findings have crucial implications on where surgical care is best provided. “Nonetheless, our current work can help address a relevant policy question central to the MISSION Act: to what extent should nonurgent veteran specialty care occur in the private sector?” they wrote. “We believe an absolute risk reduction of 0.46% is clinically significant given the trajectory of quality improvement in 30-day mortality. The mortality event rate in surgery is intentionally low, and thus small differences reflect real changes in quality.”

The study added that, since the initiation of VASQIP data collection in 1991, the 30-day mortality of major surgery in the VA decreased from 3.1% in 1991 to 2.3% in 2000 to 1.0% now, “taking almost 4 decades of quality improvement efforts to make incremental yet imperative improvements in surgical outcomes.”

The authors also pointed out that veterans in the cohort were older and more frail than patients in NSQIP, which usually is associated with a greater perioperative risk. In fact, they added, “The VHA has long been considered a safety net because, as a group, veterans have unique psychological and economic needs along with a high burden of comorbid conditions. In our adjusted analysis, VA surgical care was associated with a decreased risk of perioperative death compared with the private sector—a consistent finding across different contexts in our sensitivity analyses. The significantly lower risk of death for frail and very frail veterans suggests VA hospitals may have developed strategies to mitigate the increased perioperative risk.”

Researchers also described how effective VA surgical care has been in complication rescue. Part of the reason, they explained, was the introduction of intraoperative team training in more than 100 facilities.

“This is an adaptation of the aviation industry’s crew resource management theory that encourages working as a team in the operating room, psychological safety, and the use of preoperative and postoperative briefing checklists,” the article noted. “Facilities where training was implemented demonstrated a dose-response relationship between decreased surgical mortality and the amount of team training received with a near 50% decrease in annual mortality compared with facilities without training.”

Also widely implemented at the VHA has been clinical decision support systems able to identify critical events quickly and, in some cases, predict them, according to the study.

Researchers pointed to another factor that might be playing an outsized role in favorable surgical outcomes, explaining, “In addition to focusing on the specific delivery of surgical and perioperative care, the VA recognizes how surgical treatment is complicated by mental health, addiction treatment, transportation, and lodging considerations, and has thus consistently invested in programs to provide more holistic care to veterans across the continuum of care in ways that are likely either inadequately integrated or difficult to recapitulate in private sector settings.”

- George EL, Massarweh NN, Youk A, et al. Comparing Veterans Affairs and Private Sector Perioperative Outcomes After Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA Surg. Published online December 29, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6488

- Altan D, Leya GA, Chang DC. Untangling Access and Quality in the VA Health Care System: Measuring Black Holes in Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. Published online December 29, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6548