AURORA, CO—VA clinicians should exercise caution with use of sulfonylurea in some patients with co-morbid type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to new research.

Instead, urged a study team from the VA Eastern Colorado Healthcare System, metformin or newer diabetes medications with cardiovascular safety data might be considered as alternatives when individualizing therapy.

The recently published study raised questions about the use of sulfonylureas and increased risk of coronary artery disease in diabetic patients. It added to a significant body of research published in the last year on sulfonylureas, cardiovascular disease and mortality that suggest that one of the original medications for type 2 diabetes might do more harm than good for many patients.1

Sulfonylureas constitute one of six preferred classes of second-line treatment options recommended by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not achieve target glycemic levels with lifestyle changes and metformin alone or for patients who cannot take metformin. Until recently, the ADA did not recommend one class over another in the second line.

The VA’s guidelines continue to take that neutral stance. “The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines do not recommend any single class of medication as second line therapy. Independent practitioners prescribe a medication, using shared decision making taking into account the individual benefits, risks, and side effects of medications, and patient preferences,” according to Leonard Pogach, MD, national program director for Endocrinology and Diabetes at the VA.

In a notable change, however, the 2018 ADA guidelines now advise physicians to select as a second-line therapy a sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist or basal insulin based on drug-specific effects and patient factors in consultation with the patient, except in the case of patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. For those patients, the latest guidelines recommend choosing an agent shown to reduce cardiovascular events and mortality.

“Two new classes of medications appear to have benefit particularly in patients with cardiovascular disease – GLP-1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide and exenatide) and SGLT-2 inhibitors (e.g., empagliflozin and canagliflozin),” said Sridharan Raghavan, MD, PhD, of the Rocky Mountain Regional VAMC and the University of Colorado School of Medicine and lead author of the recent study on sulfonylureas.

Recent cardiovascular outcome trials demonstrated an advantage for two SGLT2 inhibitors—canagliflozin and empagliflozin—and the GLP-1 receptor agonists liraglutide and exenatide. Studies on pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione, indicate a potential benefit in cardiovascular disease (CVD) as well. Canagliflozin and empagliflozin also appear to benefit patients with chronic heart failure.

Conflicting Findings

Noting that studies had conflicting findings on the relative safety of metformin and sulfonylurea and that the known side effects of sulfonylureas might cause particular harm in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), the VA researchers compared the two treatments in 5,352 veterans with both CAD and type 2 diabetes who received treatment between 2005 and 2015.

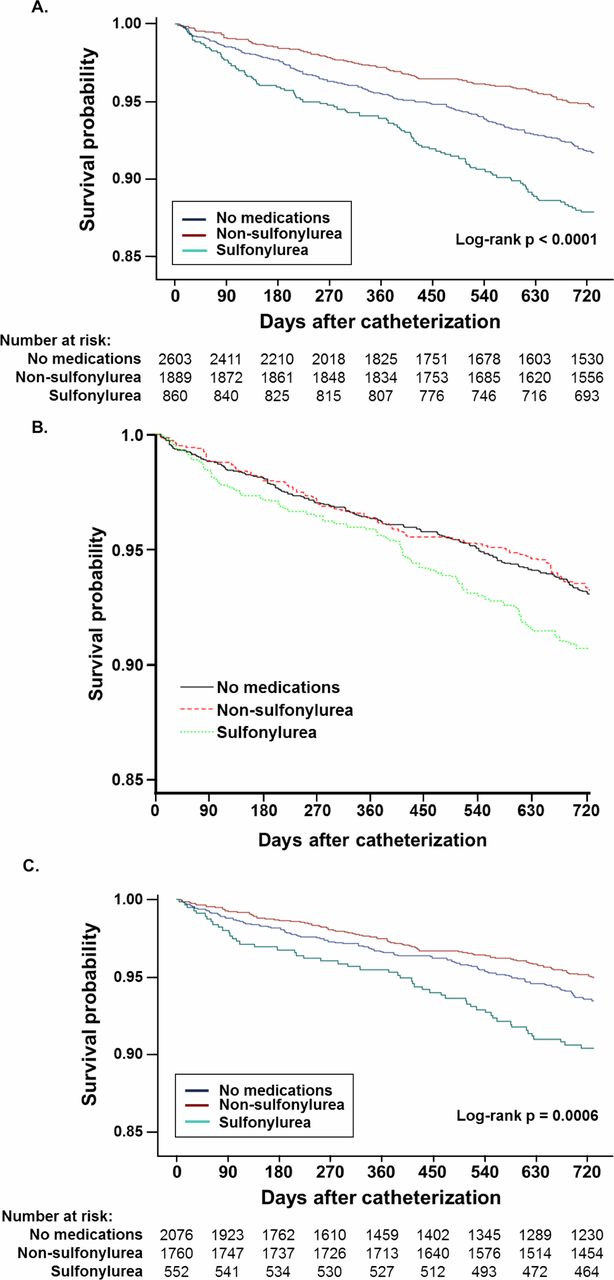

In the study published in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, the researchers accounted for stratification of patients by looking at veterans with well controlled diabetes, defined as having A1c of 7.5% or less at the time of catherization for CAD. Eligible patients took no oral diabetes medication (49%), a non-sulfonylurea, principally metformin (35%) or a sulfonylurea (16%).1

The researchers found that patients who took sulfonylureas had about twice the two-year mortality (11.9%) of those who took a non-sulfonylurea (5.2%) or no medication at all (6.6%). A fully adjusted survival model attenuated the difference, indicating that sulfonylureas might increase the mortality risk (HR 1.38 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.93), p=0.05).

The researchers concluded that in veterans “Sulfonylurea use was common (nearly one-third of those taking medications) and was associated with increased 2-year mortality in individuals with obstructive CAD.”

Raghavan noted that while metformin is the “mainstay of first line diabetes treatment and a reasonable choice” for patients with CAD, in individuals with CAD and well-controlled diabetes, “one of our conclusions was metformin or no medications at all might be suitable alternatives to sulfonylureas in the patient population that we studied.”

That does not mean that sulfonylurea has no place in treatment of these patients, however. “I tend to be very cautious about using sulfonylureas, but there remain scenarios in which they may be the most acceptable drug for diabetes,” Raghavan told U.S. Medicine. In particular, patients without cardiovascular disease who cannot take metformin or strongly oppose using insulin might be appropriate candidates, he said, as would patients outside of the VA system for whom the out-of-pocket cost is a concern.

As an older drug, sulfonylureas are commonly available in generic form. “The cost of the mediations remains an important reason why sulfonylureas are on the WHO’s essential medications list,” he noted.

While the VA research looked at a very specific patient cohort, other recent research published in the BMJ evaluated metformin and sulfonylureas in a larger and more diverse population. That study found that adding sulfonylureas to metformin therapy or switching to sulfonylureas from metformin increased the risk of myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, cardiovascular death, all-cause mortality and severe hypoglycemia.

The study included 77,138 patients in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink who started metformin therapy for type 2 diabetes between April 1998 and March 2013. Of those, 25,699 patients added or switched to sulfonylureas during the study.

The researchers determined that adding or switching to sulfonylureas rather than remaining on metformin monotherapy increased the risk of myocardial infarction 26% and raised the risk of all-cause mortality 28%. Sulfonylureas also increased the risk of severe hypoglycemia more than seven-fold. Switching to sulfonylureas rather than adding them to metformin increased the risk of myocardial infarction 51% and the risk of all-cause mortality 23%.2

An accompanying editorial pointed out that the difference in risk between adding sulfonylureas to metformin vs. switching to sulfonylurea monotherapy “could be driven by the possibility that higher doses of sulfonylureas are needed by those who switched.” Overall, though, they concluded that “continuing metformin alone and accepting higher HbA1c targets is preferable to switching to sulfonylureas when considering both macrovascular outcomes and hypoglycemia.”3

Raghavan shared that cautious approach. “My interpretation of the recent studies describing the risks of sulfonylureas is that their use should come with close surveillance for hypoglycemia and constant re-assessment of whether an alternative medication (or no glycemic medications at all) might be preferable.”

1. Raghavan S, Liu WG, Saxon DR, Grunwald GK, Maddox TM, Reusch JEB, Berkowitz SA, Caplan L. Oral diabetes medication monotherapy and short-term mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2018;6:e000516.

2. Douros A, Dell’Aniello S, Yu OHY, Filion KB, Azoulay L, Suissa S. Sulfonylureas as second line drugs in type 2 diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular and hypoglycaemic events: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2018 Jul 18;362:k2693.

3. McGowan LD, Roumie CL. Sulfonylureas as second line treatment for type 2 diabetes. BMJ. 2018 Jul 18;362:k3041.