VA research has found that about half of veterans with diagnosed schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder have attempted suicide. Nearly 70% of veterans with schizophrenia and more than 82% of those with bipolar disorder reported suicidal ideation or behavior. That’s why it is so critically important to maintain their medications during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Long-acting injectable drugs has helped the VA do that.

SEATTLE — As the pandemic swept across the U.S. and shuttered hospitals to all but COVID-19 patients, healthcare teams around the country debated the best course of treatment for their patients with severe mental illness. Should patients with schizophrenia continue on long acting injectables? Should they be switched to oral therapies to avoid the need to come into a clinic for injections?

“Ideally, patients should be seen as infrequently as medically prudent during this public health emergency, to limit the possibility of exposure (both patients and healthcare staff),” according to SMI Adviser, an initiative of the American Psychiatric Association and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“LAIs have pharmacokinetics that can be used to achieve this goal. Creative solutions may be needed to actually give the injection,” the advisory continued.

At the VA, teams took a case-by-case approach.

“It comes down to a specific decision about each patient,” said Andrew J. Saxon, MD, director of the Center of Excellence in Substance Addiction Treatment and Education, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, and professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at the University of Washington School of Medicine, both in Seattle. “What are the risks of COVID transmission if the patient comes to the clinic versus what are the risks of relapsing and getting into serious problems if they don’t come to the clinic and get an injection?”

Calculating the risk of coming in for an injection goes beyond that faced by the healthcare professional involved.

“If there are adequate supplies of personal protective equipment, then bringing in someone for an injection, the encounter should not be high risk for transmission,” Saxon told U.S. Medicine. “But how is the patient getting to the clinic? Are we putting others at risk on public transportation? In addition, PPE might vary by site and what they’re able to obtain.”

The risks of not receiving injections are clear for many patients.

“The rates of medication nonadherence are very high, and the consequences are very serious for patients with severe mental illness,” Saxon noted. “A patient who relapses could end up in the hospital and they are at higher risk for suicide.”

VA research has found that about half of veterans with diagnosed schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder have attempted suicide. Nearly 70% of veterans with schizophrenia and more than 82% of those with bipolar disorder reported suicidal ideation or behavior.1

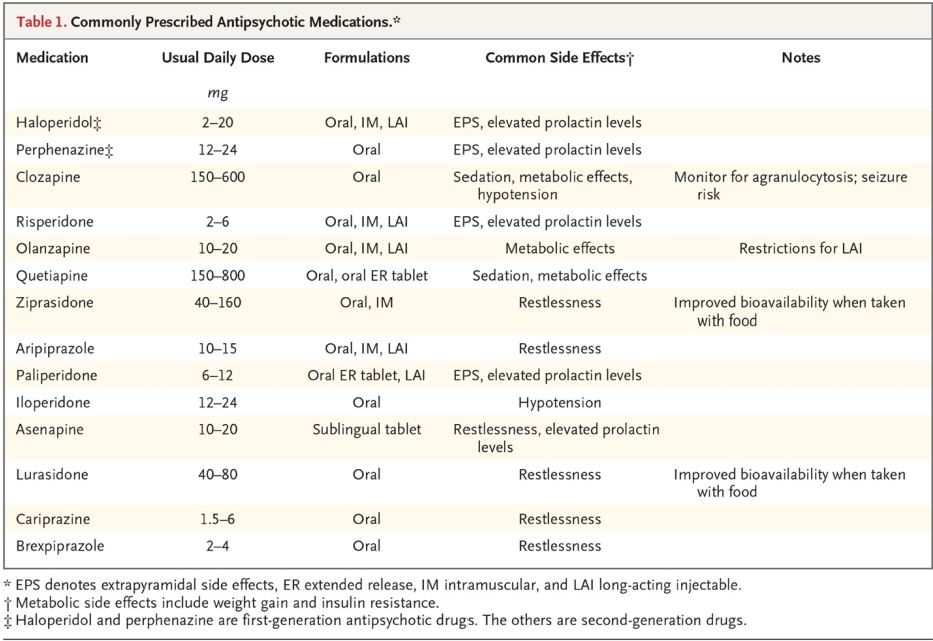

Antipsychotic medications have been delivered by injection for years, and a growing number are available that offer extended coverage.

Underutilized Option

“They’re a very good option for nonadherent patients. Unfortunately, they are underutilized for a variety of patient and provider factors,” Saxon said.

In most settings, providers find it easier to submit an electronic prescription than to order an injection, but that’s less true at the VA.

“In the VA it’s easier, because we have a strong interdisciplinary staff and resources, which makes it easier to arrange injections. For private practitioners, there are more logistics to navigate, including who’s going to give the injection,” Saxon suggested.

Randomized controlled trials may also have contributed to underutilization.

“It’s an interesting situation, because randomized controlled trials comparing injections and oral self-administration have not shown reduction in the end point of rehospitalization of schizophrenia with serious relapse,” Saxon explained.

His experience with patients and observational studies run counter to the findings of the RCTs, however. “Observational studies have showed tremendous advantage to injections,” Saxon noted. Often RCTs get squeaky clean patients with just one disorder that may not reflect a truly randomized patient sample. I believe the observational evidence.”

Adjusting LAIs

The APA and SAMHSA provide a number of suggestions for managing patients on LAIs during the pandemic, including arranging a local injection in a local clinic or pharmacy or providing injections as part of an in-home visit. In some cases, family members with a medical background might be trained to give an injection, although that would not be consistent with their labeling.

While there may be concern about changing medications during a pandemic, the organizations recommended some low-risk changes within the same medication that can increase the time between injections. Those include migrating “Invega Sustenna patients to Trinza, moving from monthly Aristada injections to dosing Aristada every six weeks or every two months.”

Arranging injections every two weeks for Risperdal Consta patients may be too difficult. A “move to Invega Sustenna or Trinza may be reasonable” for these patients, according to the SMI Adviser.

For patients in isolation or quarantine, following the information on missed doses on package guidelines can be helpful. For some medications and patients, giving a higher dose than usual may provide a buffer in case the next injection must be delayed.

While maintaining an injectable is best, staying on an antipsychotic of some form is essential, the SMI Adviser said. “If giving a LAI is not possible, temporarily prescribe oral medications again.”

- Harvey PD, Posner K, Rajeevan N, Yershova KV, Aslan M, Concato J. Suicidal ideation and behavior in US veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:216‐222. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.04.014

This is a good piece of evidence to support use of long acting injectables for veterans with Chronic Mental conditions specifically Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. I hope this research article and its likes will help provide the impetus to make it easier for psychiatric providers and prescribers to access it through our VA Pharmacy nationwide.