Exact Reasons Why Remain Mysterious

MIAMI—Since 2008, approximately 6,000 veterans have died from suicide every year. In 2017, that averaged out to just under 17 suicides among previously activated former service members each day.*

“Suicide is a national public health problem that disproportionately affects those who served our nation,” said VA Executive in Charge Richard A. Stone, MD. “Preventing suicide among veterans is VA’s top clinical priority.”

While the aggregate numbers are shocking, the individual deaths are tragic. Each ends one life too soon and negatively impacts an estimated 135 survivors, according to the VA.

Overall trends affecting veterans and the general population, which saw a 43% increase in suicides between 2005 and 2017, provide valuable information; broad outreach programs have shown success in addressing some of the issues underlying those.

Ultimately, though, every suicide arises from its own unique set of circumstances. The VA has increasingly drilled down into the data surrounding each death and each attempted suicide to better understand and mitigate the contributing factors.

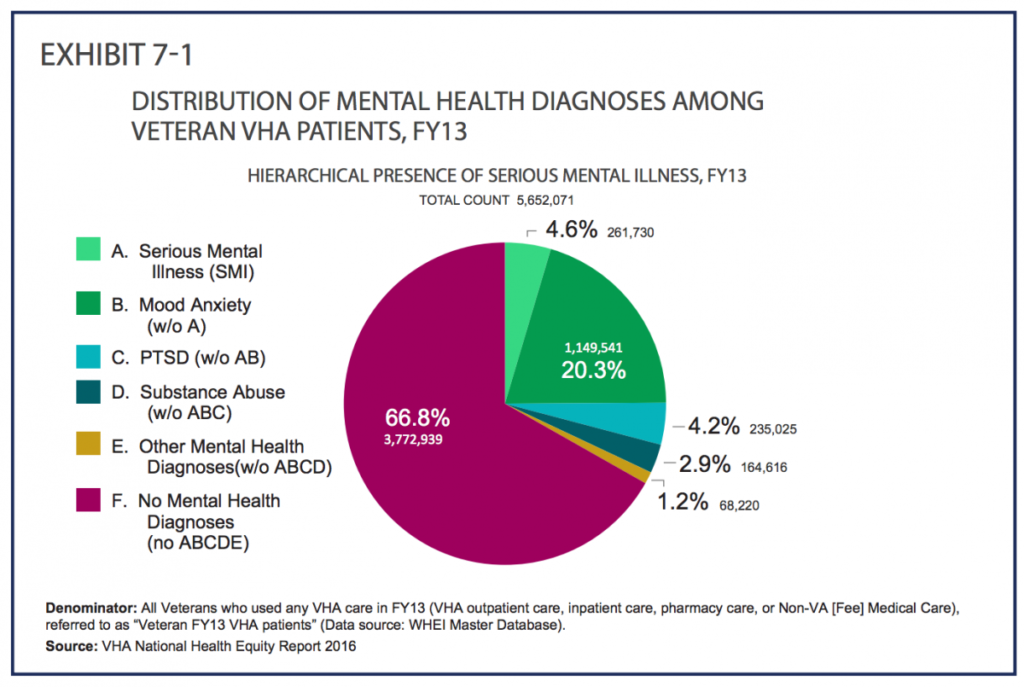

That’s driven researchers to look at more narrowly defined groups of veterans who have increased risk of suicide. A recent study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders compared suicidal thoughts, behavior, and death in male and female veterans with severe mental illness, defined for the study as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, with some surprising results.1

Notably, while female veterans with severe mental illness (SMI) had a much higher risk of attempting suicide, their overall mortality rate was 47% lower than large sample of veterans participating in the Million Veteran Program. Having more than one psychiatric illness was associated with 56% lower risk of death from any cause. About 90% of participants in the Million Veteran Program are male.

“Psychiatric comorbidities appear to be associated paradoxically with reduced risk,” the authors said. Exactly why isn’t clear.

“As we speculated in the paper, it is likely that female veterans with SMI are more likely to seek out and accept care than male veterans with the same diagnosis,” said corresponding author Philip D. Harvey, PhD, director of the Division of Psychology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; senior health scientist at the Bruce W. Carter VAMC in Miami; and editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. “That is the best thing we could think of.”

One other possible explanation put forth by the authors for the association between psychiatric comorbidities and reduced risk in female veterans included possible differences in reporting of symptoms between females and males.

The sample size for death by suicide was too small to draw conclusions and cause of death data was incomplete, but the lower overall mortality rate in females, 5.9%, compared to males, 14.3%, suggested that females in the study were less likely to die by suicide than males in the follow up period, the authors said.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from 8,049 male and 1,290 female veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder type 1, all of whom completed questionnaires and participated in in-person evaluations between 2011 and 2014. The researchers also collected genomic information on the participants. Follow up ranged from four to seven years after enrollment.

“To the best of our knowledge, this group represents the largest study population of veterans, and especially of female veterans, with confirmed SMI studied in person,” according to the authors.

The size of the study and the number of females who participated enabled deeper analysis and provided new insights.

Continue Reading this Article: Suicide Rates