David Clark, ScD, a researcher at the Brain Rehabilitation Research Center at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, FL

GAINESVILLE, FL — When people want to describe themselves as uncoordinated, they might say they have trouble walking and chewing gum at the same time. However, the act of walking—one of the most basic human skills—is not nearly as simple as that phrase makes it sound.

David Clark, ScD, a researcher at the Brain Rehabilitation Research Center at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, FL, stresses that walking is not a single task but rather a complex series of neurological events that can become more difficult as a person ages.

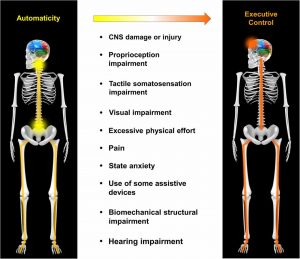

“If you think about your legs, there are several joints that can move in many different directions. There are dozens of muscles. And your nervous system doesn’t have to think about which muscle to contract and what joint to move. All of these complex motions are done automatically,” Clark explained. “We have circuits in our nervous system that take care of that complexity. They produce those patterns of muscle activation for us, so we don’t have to think about it. What happens when people get older or when people have a neurological injury, like a stroke—that automaticity of movement is impaired.”

With a background in exercise physiology and a doctorate in rehabilitation sciences, Clark has devoted his career to understanding how the nervous system adapts to rehabilitation and how therapy can be improved so that walking-impaired veterans can lead safer, healthier lives.

Cognitive Task

“I don’t think people realize that walking becomes a cognitive task as people get older. It becomes taxing on your brain to think about how to control your movement, and it makes people more susceptible to falling. That’s why we care about it. We don’t want people to fall and get hurt,” Clark explained.

Like in many research endeavors, the first challenge has been figuring out how to measure impairment and improvement.

“One of the main things is understanding how to measure restoring control. How do we measure whether someone has more automatic control or whether walking is more cognitively demanding?” Clark asked.

The answer he and his fellow BRRC researchers have hit upon is functional near-infrared spectroscopy. By measuring changes in near-infrared light, it allows them to monitor blood flow to the front part of the brain. “It’s sort of a headband we have people wear that has technology in it that lets us measure how active their brain is while they’re walking,” Clark explained.

Continue Reading: