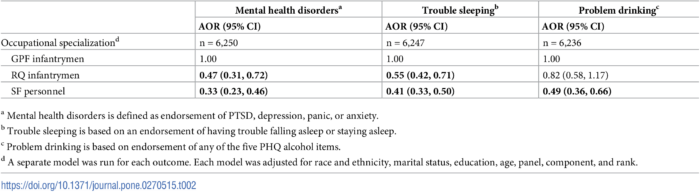

Click to Enlarge: Adjusted odds ratios for screening positive for mental health disorders, trouble sleeping, and problem drinking by occupational specialization. Source: PLoS One

SAN DIEGO — Experiencing combat during deployment has been associated with adverse health outcomes including mental health problems, sleep problems and alcohol misuse. The majority of studies have defined combat broadly and have focused on conventional forces, however, and the effects of specific exposures—particularly among specialized soldiers who are selected into and complete arduous training courses—are not as well understood.

“It is important to identify unique risk factors and whether the impact of various types of combat exposures differ by occupational specialization in order to appropriately tailor intervention strategies,” explained Anna Rivera, MPH, an epidemiologist with the Navy Health Research Center in San Diego. Rivera led a new study to examine the association between different types of combat exposures and behavioral outcomes, and whether these associations are different by Army occupational specialization.

The study, which was published in PLoS One, leveraged existing data from the Millennium Cohort Study, the military’s largest prospective cohort study designed to investigate the effects of military service on health over time, said Rivera.

The study sample was restricted to U.S. Army personnel who served in one of the three occupational specializations: General Purpose Forces (GPF) infantrymen, RQ infantrymen and SF personnel who had completed at least one deployment in support of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. SF personnel included weapons, engineer, communications, intelligence and medical sergeants who passed a selection course and completed a 12- to 18-month Special Forces Qualification Course; RQ infantrymen included those who had completed Ranger School and were awarded the Ranger Tab; and GPF infantrymen included only non-RQ infantrymen. 1

Participants’ responses to survey questions on combat and health experiences were used to define the types of combat exposures and health outcomes examined.

Types of combat exposures included:

- Fighting (being attacked or ambushed, receiving small arms fire, or clearing/searching buildings),

- Killing (being directly responsible for the death of an enemy combatant or being directly responsible for the death of a noncombatant),

- Threat to oneself (having an improvised explosive device explode near you or being wounded or injured),

- Death/injury of others (seeing dead bodies, handling human remains, knowing someone injured/killed, seeing Americans injured/killed or having a unit member injured/killed),

- Type of killing (enemy combatant vs. noncombatant, and

- Severity (measured by the number of these individual situations the soldiers endured).

Outcomes included mental health disorders, trouble sleeping and problem drinking. Statistical methods were implemented to determine the associations between each type of combat exposure and each outcome of interest. Additional analyses were conducted to determine if these associations differed by occupational specialization.

Types of Combat Exposures

Rivera cited two main findings: “One, various types of combat exposures—for example, combat severity, fighting, threat to oneself and killing noncombatants—were consistently associated with mental health disorders, trouble sleeping and problem drinking, regardless of occupational specialization”, she told U.S. Medicine. “Two, in general, RQ infantrymen and SF personnel had lower prevalence of these adverse health outcomes compared with GPF infantrymen”.

Results indicated that those who were responsible for the death of either an enemy combatant or noncombatant had the most consistently elevated odds of all three health outcomes examined, regardless of occupational specialization, she said, adding. “Furthermore, when we distinguished between types of killing, results indicated those who were responsible for the death of a noncombatant were more likely to experience adverse outcomes compared with those who were responsible for the death of an enemy combatant only.”

The authors suggested that being directly responsible for the death of a noncombatant may go against the servicemember’s moral code, whereas killing an enemy combatant may eliminate a potential threat, serve as a marker of operational success and be regarded as consistent with the warrior ethos, they wrote. “Events that challenge the moral and ethical foundation of service members can influence all aspects of their lives, contributing to mental and physical health problems. Thus, killing a noncombatant may have a distinct, negative effect on service member well-being,” according to the study.

The authors posited that training incorporating frank dialogue about handling these kinds of experiences and moral reasoning might enable servicemembers to better prepare for difficult decisions that may arise during combat, noting, “Those experiencing moral distress after combat may benefit from interventions that emphasize meaning making as well as acknowledging and accepting the moral conflict they may have encountered,” they wrote.

“Units and team leaders can also work together to support service members in the wake of such experiences,” the authors continued. “These recommendations are relevant to GPF infantrymen, RQ infantrymen, and SF personnel, all of whom receive extensive training for combat with the expectation they may engage in killing combatants as part of their operational role.”

This training and other interventions may need to be tailored to specific occupational groups, they concluded.

- Rivera AC, Leard Mann CA, Rull RP, Cooper A, Warner S, Faix D, Deagle E, Neff R, Caserta R, Adler AB; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Combat exposure and behavioral health in U.S. Army Special Forces. PLoS One. 2022 Jun 28;17(6):e0270515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270515. PMID: 35763535; PMCID: PMC9239470.