Rates More Than Doubled in 15-Year Observation Period

WASHINGTON, DC ― VA recently announced that it has awarded $52 million in grants to 80 community-based organizations to deliver or coordinate suicide prevention programs and services for veterans and their family members. This is in line with statements from department leaders on how suicide prevention efforts can be most effective, if undertaken locally and targeting veterans where they live.

A House Veterans’ Affairs committee hearing last month highlighted some of the local efforts those grants will help support, most notably among Native veterans. It also gave VA leaders an opportunity to push back against independent research from one of the other grantees―the American Warrior Project (AWP)―that suggests VA is undercounting veteran suicides.

The suicide rate for Native Americans has doubled over the past 15 years, with Native veterans considering suicide at a higher rate than any other ethnic group. At the same time, there is both a lack of research targeting Native veterans and the same gaps in care that impact all veterans in rural areas.

“Over the past three years, more than 80% of the veterans served by Cherokee Nation’s Behavioral Health department have had thoughts of suicide. Now, more than ever, it is critical for our veterans to have ready access to mental health care and social services,” explained Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, the country’s largest tribal government.

A study earlier this year found that American Indian and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) veterans appear to be at elevated risk for suicide. Researchers led by VA’s Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for Suicide Prevention in Colorado conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of AI/AN veterans who received healthcare services provided or paid for by VHA between Oct. 1, 2002, and Sept. 30, 2014, and who were alive as of Sept. 30, 2003.

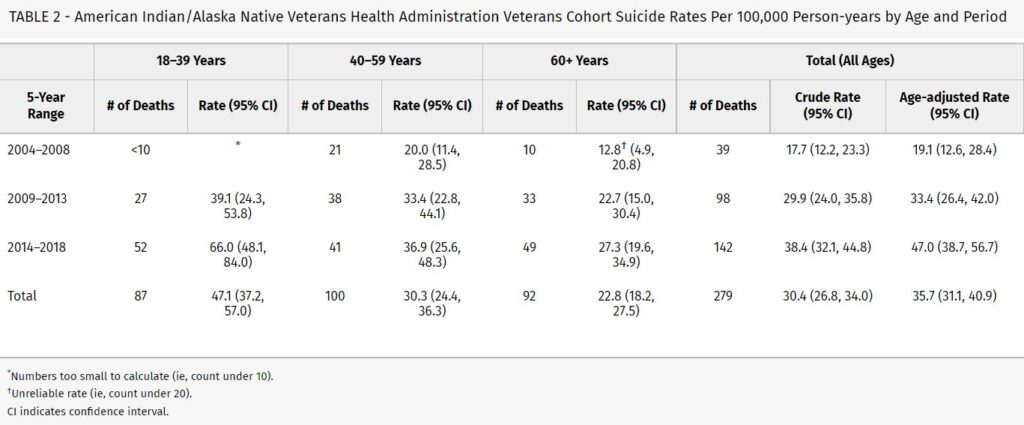

The study, published in the journal Medical Care, found that age-adjusted suicide rates among AI/AN veterans more than doubled (19.1-47.0/100,000 PY) over the 15-year observation period. “In the most recent observation period (2014-2018), the age-adjusted suicide rate was 47.0 per 100,000 PY, with the youngest age group (18–39) exhibiting the highest suicide rate (66.0/100,000 PY). The most frequently used lethal means were firearms (58.8%), followed by suffocation (19.3%), poisoning (17.2%), and other (4.7%),” the authors pointed out.1

The $750,000 grant awarded to the Cherokee Nation by VA will help launch the Cherokee Nation Veteran Suicide Prevention Program (CNVSPP). The program will implement a process for veteran suicide screening; a surveillance system of individuals who screened positive; and a therapeutic framework for addressing suicidal behaviors in veterans and their families.

In the neighboring Choctaw Nation, the grant will be used for something simpler but equally important: the hiring of much-needed staff.

“With this funding, the Nation will hire one counselor and two peer recovery support specialists,” testified Shauna Humphreys, MS, director of behavioral health for the Choctaw Nation. “This will provide jobs to people who are living in recovery and can share their experiences to help and support others in similar situations.”

“One exciting part of this grant is that group services for veterans’ families will be established,”Humphreys added in her written statement. “Many times, family members can save a life if they are educated and informed on what to say and do in serious situations. We want to empower families to help their loved ones and save lives within our community. We believe mental wellness has a ripple effect, if one individual is helped, it leads to a healthier person, to healthier families, healthier communities, and ultimately, a healthier Choctaw Nation.”

One of the biggest challenges in tribal areas, most of which are rural, is staffing. In 2017, the overall vacancy rate for providers in the Indian Health Service (IHS) was 25%, ranging from 13% to 31% depending on the geographic area.

“A great challenge in Indian country and probably for much of the country, certainly rural America, is making sure we have enough professionals staffed and in the pipeline coming up to take on these challenges,” Hoskins said. “It’s heartbreaking to think about veterans we may not reach because we may not have as many professionals on staff to reach them. We have to confront that, though, as a country. We certainly have to confront that as a Cherokee Nation.”

Committee Chairman Rep. Mark Takano (D-CA.) used conversation around the hiring shortage to highlight why relying on community care instead of VA and IHS is untenable.

“I don’t see how we push people into the community if there’s no one in the community to take care of them,” Takano said. “And frankly, I don’t see how we stand up facilities or practitioners in these areas without some sort of federal presence. This debate―internal capability versus care in the community―I think we have to move beyond that debate and ask the real question. How do we get practitioners, professionals, and real staffing into rural America and Indian country?”

Conflict in Suicide Statistics

During the hearing, VA officials were grilled on their recently released veteran suicide numbers, and the difference between the VA statistics and those compiled by AWP’s Operation Deep Dive, which counted 37% more veteran suicides over the same period.

“I would not be sitting in front of you if I didn’t have 100% confidence in the data that we present on an annual basis,” Matthew Miller, VA’s national director of Suicide Prevention, told the committee. “That data I am 100% confident represents the fullest and most accurate information that we have on veteran suicide.”

He disagreed with several aspects of AWP’s methodology and noted that their report lacks specific definitions for who counts as a veteran and what counts as a suicide.

“I think it’s important to understand apples versus oranges and their report offers an apples versus orange comparison [to VA’s data],” Miller said.

AWP President Jim Lorraine testified that the difference in numbers was not Operation Deep Dive’s most profound takeaway.

“Our biggest finding was that county and state officials didn’t have the ability to recognize who served in the military and who didn’t,” he told legislators. “As a veteran, I’m troubled that there are a lot of veterans out there who were buried without military honors. If you don’t get the data right at the local level, it’s not right by the time it gets to the national level.”

One recommendation made by AWP is that VA and DoD provide an online tool, so that coroners and medical examiners can enter a deceased individual’s name and social security number and find out whether they served in the military.

Lorraine also noted that the end goal of Operation Deep Dive is not only compiling statistics, but to use those numbers to better shape outreach efforts at the local level. However, without more cooperation from VA, they were lacking sorely-needed data.

“We have a three-piece puzzle. We already have military service, and we have death,” Lorraine said. “What we don’t have is the middle piece, which is their VA experience, both VBA and VHA. If we had a complete picture of that, then we could add in access to home loans, access to disability benefits, on top of their healthcare experience. We could get a really good longitudinal picture from the time they began their service to the time they died.”

- Mohatt NV, Hoffmire CA, Schneider AL, Goss CW, Shore JH, Spark TL, Kaufman CE. Suicide Among American Indian and Alaska Native Veterans Who Use Veterans Health Administration Care: 2004-2018. Med Care. 2022 Apr 1;60(4):275-278. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001656. PMID: 35271514; PMCID: PMC8923357.