A shipment of Herbicide Orange in 208-liter drums. The lid (top) of each drum specified the content (Herbicide Butyl Esters of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T), the Federal Specification Number (FSN), US Port of Embarkation (Mobile, Alabama), destination (ARVN 511th Ordinance Storage Depot, Da Nang, Vietnam), procurement information (including date, 8/67), and net weight. Each of the 11 different companies that manufactured military herbicides packed them in new 208-liter 18 gauge steel drums for shipment to Southeast Asia. Each herbicide drum was also marked with a 7.6 -centimeter color-coded band around the center to identify the specific military herbicide (Photograph courtesy of A. L. Young).

WASHINGTON, DC ― VA claims processors have consistently failed to understand the department’s own regulations when it comes to Vietnam veterans presenting with certain Agent Orange-related conditions, prematurely denying benefits for thousands, according to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.

For decades, VA has denied most disability claims by Vietnam veterans for peripheral neuropathy, chloracne, and porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) ― a disorder characterized by the thinning and blistering of the skin in sun-exposed areas. Between 2003 and 2021, only 11,000 out of the estimated 130,000 veterans presenting with those conditions (about 8%) were granted benefits.

Unlike other presumptive conditions associated with Agent Orange, VA requires that these have manifested within one year of returning from service in order for a veteran to be eligible for benefits. If a veteran cannot prove it manifested within that time, they must otherwise demonstrate a direct service connection.

During interviews with VA claims processors, GAO investigators regularly heard inaccurate statements about when that one-year manifestation requirement applies and what evidence can be used to support service connection.

“Claims processors we interviewed at two of three selected VBA regional offices stated that they cannot grant Vietnam veterans’ claims for [these conditions] unless they have medical documentation of the condition from during military service or within one year of exposure to Agent Orange,” the report states. “For example, they said that they could not use a positive VA medical opinion linking the veteran’s condition to Agent Orange to support a decision to grant benefits if they did not also have medical documentation of the condition within one year of exposure. However, according to VA’s claims processing procedures, citing a positive medical opinion is one way claims processors can support a decision for direct service connection, regardless of when the condition was diagnosed or when symptoms first occurred.”

‘At Least as Likely as Not’

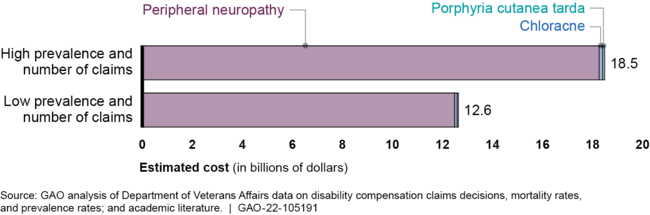

Click to Enlarge: Estimated 10-Year Cost of Disability Payments from Removing 1-Year Requirement for Three Selected Conditions, with High and Low Assumptions for Disease Prevalence and Number of Claims Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office

In four out of the 50 randomly selected claims decisions, VBA denied benefits after VA medical examiners had provided positive medical opinions stating that the patients’ conditions were “at least as likely as not” caused by exposure to Agent Orange.

While the investigators admitted this is not proof the benefits were incorrectly denied, it suggests that claims processors were focused on the one-year manifestation period and did not understand that veterans could still attempt to prove direct service connection.

Of those four cases, three would later be overturned by VA’s Board of Appeals, based in part on those positive medical opinions. In two of the cases, claims processors did not mention the medical opinions at all, and in the third it was mentioned, but the process did not explain why it was not considered sufficient evidence to grant benefits.

In one of the three cases, the judge wrote that VBA’s decision “was clearly and unmistakably erroneous” and that the processor misunderstood a provision of federal regulation related to evaluating service connection.

Claims processors also failed to understand how lay evidence could be used to support a veteran’s claim. During interviews, processors told GAO that they could not use personal statements from veterans or family members about when they first noticed symptoms in order to address the one-year manifestation period, saying the only acceptable evidence would be medical documentation during military service or the one-year following exposure.

However, due to the 50 years that have passed, lay evidence and recent medical evaluations may be all that a veteran can access. Also, in speaking with veteran service organizations, GAO investigators learned that many Vietnam veterans did not seek medical treatment immediately following their return, because symptoms were mild at first, or they did not realize they had a serious condition that would not resolve on its own.

VA’s own regulations state that lay evidence, such as a veteran’s ability to describe when and how their condition manifested, can be presented as evidence. Of those 50 selected cases, another three were later overturned because VBA failed to take lay evidence into account.

GAO’s investigation came about due to a provision in the Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020. The bill also asked GAO to evaluate what would happen, should the one-year manifestation period be lifted, and the three conditions treated like other presumptive conditions related to Agent Orange.

According to GAO, this could cost VA $16.7 to $25.8 billion over 10 years, granting new benefits in the first year, following the rule change to between 130,000 and 217,000 veterans.