Study Found Science to Confirm Relationships Lags

Master Sgt. Darryl Sterling, 332nd Expeditionary Logistics Readiness Squadron equipment manager, tossed unserviceable uniform items into a burn pit in March 2008 in Balad, Iraq. Now, a new report discusses symptoms and illnesses that could be related to the fumes. Photo by Senior Airman Julianne Showalter.

WASHINGTON — Are burn pits becoming the new Agent Orange for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan? This is one of the issues worrying legislators and veterans’ advocates, who see parallels not just in the myriad symptoms linked to burn pits, but also in the too-slow scientific progress understanding their relationship.

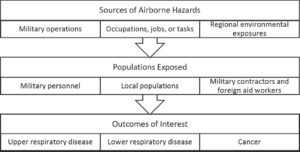

Those concerns have been fed by a recent National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report which linked particular symptoms to burn pits but found that the science currently does not exist to be able to determine the relationship to specific illnesses.

Military bases throughout Iraq and Afghanistan regularly used open-air burn pits to dispose of waste. Reports have found that the pits were used to burn anything and everything a base needed to dispose of, including human waste, medical waste, plastic, metal, electronics, unused ordinance and various chemicals. Burn pits used jet fuel as an accelerant, creating giant black plumes of smoke that could be seen for miles and released a variety of toxins into the air.

While the toxins released by burn pits have been linked to cancers, autoimmune disorders and more, the majority of complaints by veterans have centered on respiratory problems such as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, sleep apnea, bronchitis and sinusitis.

“The evidence for respiratory symptoms—which included chronic persistent cough, shortness of breath, and wheezing—met the criteria for limited or suggestive evidence of an association for both veterans who served in the 1990-1991 Persian Gulf War and those who served in the military operations after Sept. 11, 2001 attacks,” Mark Utell, MD, chair of the NAS committee that wrote the report, said in a statement.

Addressing the lack of conclusive evidence linking burn pits to specific diseases, he added, “New approaches are needed to better answer whether respiratory health issues are associated with deployment. The current uncertainty should not be interpreted that there is no association. Rather, the issue is that the available data are of insufficient quality to draw definitive conclusions.”

At a House VA subcommittee on disability assistance hearing last month, legislators asked representatives from NAS and VA what would be required to go from limited or suggestive evidence to firm conclusions.

The biggest problem NAS found was the lack of documentation while servicemembers were in-country, explained Sverre Vedal, MD, MPH, a pulmonologist and professor of environmental science at the University of Washington.

“Information was often lacking on who was exposed, what they were exposed to, where and when and over what time period and frequency,” Vedal, who worked on the NAS committee, testified. “We were well aware of testimonials reporting conditions related to service. We were expecting, I think, to see some associations based on the literature, particularly for asthma and sinusitis. But we were disappointed.”

Emerging Technology

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Respiratory health effects of airborne hazards exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25837.

He noted that technological advances would allow scientists to better understand what toxins were released in what areas is now emerging.

“The current science for exposure assessment is often pretty crude. Often, it’s whether a servicemember was deployed versus nondeployed,” Vedal explained. “One of the most exciting technologies is using remote sensing from satellites to estimate previous historical exposure in theatre. NASA information on burn in theatre can be used for that purpose to historically estimate exposures.”

The NAS report also recommends that VA commit to more, better studies on respiratory disease mortality in southwest Asia theater veterans and that VA and DoD plan for better tracking of exposure in the future.

VA has taken some steps to track the health of veterans exposed to burn pits, most notably with its Airborne Hazard and Open Burn Pit Registry, which has documented more than 213,000 veterans exposed while in service.

“The registry has been very helpful to data-mine it for trends and to be able to create cohorts for studies,” explained Patricia Hastings, DO, VA’s deputy chief consultant for post-deployment health services. “Unfortunately, it’s an opt-in system … If it was an opt-out system, that would make it easier for us to track them.”

In the meantime, legislators are wondering what can be done to help veterans suffering from illnesses that might be caused by burn pit exposure to get VA benefits and healthcare.

“I understand that it’s difficult to create a one-size-fits-all solution to toxic exposure when science is lagging behind. But what we cannot do is continue to delay and deny while veterans suffer with service-related diseases,” declared Rep. Elaine Luria (D-VA).

From June 2007 through July 2020, 12,582 veterans sought benefits for conditions related to burn pit exposure. Of those, VBA approved 2,828 for one or more conditions. VBA officials assured the subcommittee that minimal information is required to confirm exposure to burn pits and that, when there is doubt, the benefit goes to the veteran.

Asked why VA shouldn’t create a presumptive service connection, such as what the department eventually did with Agent Orange, VA physicians said it might do more harm than good.

“If I cut off the science right now and said everyone gets benefits for burn pits and I don’t care about the science anymore, some people will be harmed,” Hastings explained. “There are some people who have respiratory symptoms that are not referable to burn pits. Some people with PTSD, with blast injury have respiratory symptoms. We really do want to get to the right diagnosis, right treatment and right care for that veteran.”

Hastings also told the subcommittee that understanding the impact of burn pits will not take as long as it did with Agent Orange.

“Agent Orange is what we learned a lot from. We didn’t know about the dangers at the time,” she explained. “We’ve learned that we continuously need to look at what are the concerns from veterans. What are we seeing in the registry. Yes, it’s self-reported data, but it can give us an idea of what we need to look at. We are actively researching constantly.”