WHITE RIVER JUNCTION, VT — For more than a decade, the VA has pushed evidence-based psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatments nationally have slowly and steadily increased.

The question raised in a recent Military Medicine study, however, is how consistent the practice has become, whether there is geographic variation in initiation of EBP and identification of patients and clinic factors associated with its use.1

To accomplish that, White River Junction, VT, VA-led researchers used retrospective electronic medical records data to identify 946,667 VA patients with PTSD who had not received EBP as of January 2016 and whether they had initiated the treatment by December 2017.

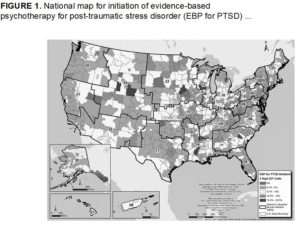

Results indicated that, nationally, 45,895 veterans, 4.8%, began EBP from 2016 to 2017. There was a geographic variation, however, ranging from none to almost 30% at the three-digit ZIP code level, according to the report.

Researchers determined that the strongest patient predictors of EBP initiation were the negative predictor of being older than 65 years (OR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.45-0.49) and the positive predictor of reporting military-related sexual trauma (OR = 1.96; 95% CI, 1.90-2.03). At the same time, they reported, the strongest regional predictors of EBP initiation were the negative predictor of living in the Northeast (OR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.92) and the positive predictor of living in the Midwest (OR = 1.47; 95% CI, 1.44-1.51).

The only nearest VA facility predictor of EBP initiation was the positive predictor of whether the facility was a VAMC with a specialized PTSD clinic (OR = 1.23; 95% CI, 1.20-1.26), according to the study.

“Although less than 5% of VA patients with PTSD initiated EBP, there was regional variation. Patient factors, region of residence, and nearest VA facility characteristics were all associated with whether patients initiated EBP,” the authors concluded.

Targeting Areas

Researchers wrote that the strengths of their study included the use of national longitudinal data, while weaknesses include the potential for misclassification of PTSD diagnoses and potential for misidentification of EBP, adding, “Our work indicates geographic areas where access to EBP for PTSD may be poor and can help target work improving access. Future studies should also assess completion of EBP for PTSD and related symptomatic and functional outcomes across geographic areas.”

Background information in the article pointed out that the VA requires all VAMCs to provide access to one of two evidence-based psychotherapies—prolonged exposure (PE) and cognitive processing therapy (CPT). While requirements for community-based outpatient clinics vary by size, VA documents require access for all veterans either in person or by telehealth, the researchers noted, explaining, “There have been substantial national efforts to implement CPT and PE, resulting in slow but steady increases in use and quality of EBPs in routine practice. However, when followed over time, less than 20% of VA patients with PTSD ever initiate EBPs. The delays to treatment are substantial, with over two-thirds of patients who initiate EBPs doing so more than a year after initial presentation at VA mental health clinics.”

In this study, the authors said their objectives were to: (1) determine whether there is geographic variation in the initiation of EBP among VA patients with PTSD nationally and (2) determine whether EBP initiation is associated with patient, regional (geographic), and/or local VA facility characteristics.

“Given the focus on specialized PTSD treatment settings in prior implementation studies, we hypothesized that patients living closer to VA facilities with these resources would have higher rates of EBP initiation,” they wrote. “This information will indicate whether approaching disparities in EBP use should focus on individual patient or health system factors.”

- Dufort VM, Bernardy N, Maguen S, Hoyt JE, et. Al. Geographic Variation in Initiation of Evidence-based Psychotherapy Among Veterans With PTSD. Mil Med. 2020 Nov 13:usaa389. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa389. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33185663.