Agency Not Sure How Many Veterans Are Using the Program

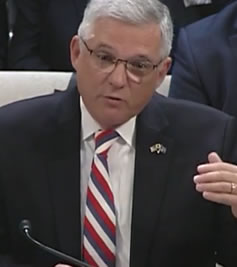

VHA Executive in Charge Richard Stone, MD, said recently he was concerned that MISSION Act could be over budget. The photo shows him testifying before Congress last year. VAntage Point photo

WASHINGTON—Nine months after the MISSION Act went live, VA is still unsure how many veterans are taking advantage of the revamped community care system and how much it will cost the department in its first year, VA leaders told members of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs.

The admission last month came on the heels of a VA Inspector General report that suggests wait times for appointments could worsen under the new system. Compounding legislators’ worries about the program are difficulties in finding enough community network providers to care for veterans in rural areas, as well as reports from community providers about delays in receiving payment from VA.

Legislators voiced concerns that the MISSION Act could go the way of previous community care initiatives, with the program failing to provide what it promised or forcing VA to come to Congress for more funding.

Prior to the MISSION Act going into effect, VA predicted demand could increase from 648,000 veterans receiving appointments from non-VA providers each year to 3.7 million. From the June launch through the end of January, VA had placed more than 3.6 million referrals to community care providers. But the number of those referrals that are translating into actual visits by veterans to non-VA providers is still unknown.

“In 2017, Congress stepped in three times to provide additional funding for the department so it would not exhaust the CHOICE program funding,” noted Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT), referring to the community care program that the MISSION Act is replacing. “I’m concerned we’re heading down that path again. Are you concerned that VA may be over budget with this program?”

“That’s the question that keeps me up at night,” responded VHA Executive in Charge Richard Stone, MD. “The appointing and authorizations have not turned into bills coming back in. We have better criteria in our regulations now as to how long a vendor has to bill us. We’re using the Medicare standard—a 180-day deadline to bill. And we’re still waiting for bills to come in.”

Once VA has processed payments, it will have a better idea of how many veterans are actually using community care under the new program and how much it will cost overall.

“It appears that authorizations are beginning to drop,” Stone added. “We predicted that there would be some kicking of the tires for community care and then it would drop off.”

Payment Delays

Several senators noted, however, that the delays are not always on the providers’ end. One senator mentioned large providers who have millions of outstanding bills for VA patients, while a smaller one has more thanr $20,000 in outstanding bills.

“We’re not where we should be,” Stone admitted. “We’re changing antiquated systems. And this problem is not our third-party administrators. This is internal to VA. Our processes do overwhelming oversight to every bill and it slows the process down.”

Kameron Matthews, MD, JD, Assistant Under Secretary for Health for Community Care, explained to the committee that VA audits every claim prior to payment to avoid the fraud and waste of overpayment. “It’s a significant amount of work that, unfortunately, is quite manual,” she said.

Senators also voiced their concern that the access standards built into the MISSION Act limiting drive times and wait times for veterans seeking care are not being included in several of the new regional community network contracts.

Matthews explained that, in some areas of the country, the scarcity of providers makes adding those standards to the contract untenable. “We’re recognizing that, contractually, there’s no way we could hold the network accountable to a level of accuracy that just doesn’t exist in the industry.”

Stone added that, even after a network of community care providers goes live, VA and the third-party network administrators will work to add providers and fill in gaps. “I think we can resolve this,” he said. “I just don’t think the American commercial healthcare systems are prepared to comply in the manners we’d like to.”

Stone also spoke to VA’s internal hiring difficulties, coming back to a topic he’s testified on before—the hiring caps that limit VA’s effectiveness in attracting providers.

“One of our biggest problems is that very high-cost specialists exceed the pay caps that we have,” he declared. “A gastroenterologist can finish their residency and come out and command a $375,000 salary. We’re capped at $400,0000. So we have trouble recruiting in certain high-cost specialties. And that’s something we’re going to have to deal with. I’ve got over 300 specialists who are at their pay caps today.”

This inability to fill high-cost specialist roles has a trickle-down effect on other jobs, he explained. “There’s no use hiring a neurosurgery nurse if I can’t hire the neurosurgeon. In California alone, one of the really high-cost markets for us, I’ve got over 400 nursing openings because we can’t compete. UCLA, just across the highway [from our LA] campus is picking off huge numbers of our nurses because we just can’t compete because of the pay caps.”

Even if the VA and its partners are able to stand up a series of community care networks that meet the standards contained in the MISSION Act, there remains the challenge of helping veterans decide whether community care is right for them.

Adrian Atizado, deputy national legislative director for the Disabled American Veterans, questioned whether VA is situated to provide that kind of nuanced decision-making assistance.

“If we’re talking about a healthy veteran, empowering them to make a choice would be a relatively easy lift,” Atizado explained. “But if we’re talking about [an] older, aging [veteran] with lifelong conditions, the kind of information they’re looking for is more meaningful. For example, if you’re suffering from multiple sclerosis, you’re looking at information that would be able to tell you as a patient [whether] you would want to have a lifelong relationship with this doctor. Can I drive to them if they were far? If they were of that value to me in my life and would effect my ability to be an active member of society?”