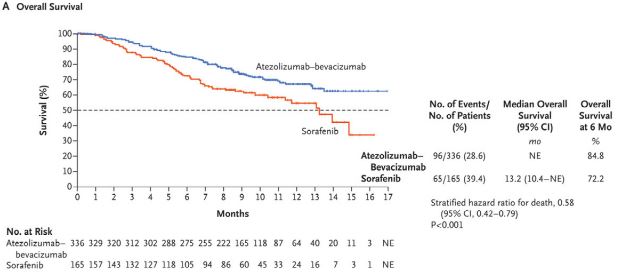

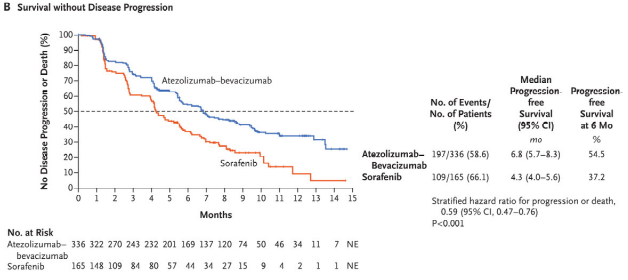

Kaplan–Meier Analysis of Overall and Progression-free Survival. |

KANSAS CITY, MO — Without treatment, even patients diagnosed with early stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have a median survival of just over a year. Patients with advanced stage disease at diagnosis will likely see just one change of season.

Fortunately, treatments are available. If HCC is caught early enough, patients have a chance at curative treatment—either surgical resection or transplantation. Resection is suitable for patients without cirrhosis or portal hypertension, but two-thirds of resected patients will experience recurrence within five years. Transplantation has better long-term results, with a four-year survival rate north of 80%.

Unfortunately, the curative treatments are not available to most people who develop HCC, largely because their cancer is not caught early enough. In the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines version 2.2021 for hepatobiliary cancers, locoregional therapies such as transarterial embolization or radiotherapy, which can slow growth of unresectable tumors, are preferred for patients ineligible for surgery with liver-confined diseases.

Other locoregional options for unresectable HCC and patients unable to tolerate surgery include external beam radiation therapy, 3D conformal radiation therapy, and intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) “can be considered as an alternative to ablation/embolization techniques or when these therapies have failed or are contraindicated,” according to the NCCN. SBRT is recommended for one to three tumors and “could be considered for larger lesions or more extensive disease, if there is sufficient uninvolved liver and liver radiation tolerance can be respected,” the guidelines noted. Clinical trials and certain systemic therapies are also options. TARGETE

Classic cytotoxic chemotherapies used for other cancers provide limited benefit in HCC. “Hepatocellular carcinoma or primary liver cancer is not really sensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy—the nausea, vomiting, lose-your-hair kind of chemo therapies,” said January Fields-Meehan, MD, an attending physician in the department of hematology and medical oncology at the Kansas City VAMC in Missouri. “We don’t know why; it could be the cells divide too slowly or they’re not in their cell cycle stages long enough. It would make sense that they would be sensitive because they’re highly vascular,” Fields told U.S. Medicine, but “there’s something different about those tumors.”

The high degree of vascularization, however, increases the effectiveness of therapies that target the vascular endothelial growth. A number of targeted therapies and immunotherapies gained U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for advanced and metastatic HCC in the last four years. They joined sorafenib, the first drug approved for liver cancer, which provided the only systemic treatment from 2005 until 2017.

The new therapies fall into two classes. Those targeting tyrosine kinase receptors include regorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab. The immunotherapies—nivolumab, ipilumumab, and pembrolizumab—aim to reverse T-cell exhaustion and keep tumor cells from spreading.

Combinations Are the Future

In the last year, “there’s been a new frontline regimen that’s been FDA approved and that is atezolizumab plus bevacizumab,” Fields explained. “That is a combination of immune therapy along with a targeted therapy that is delivered by IV.” NCCN lists atezolizumab-bevacizumab as the preferred regimen for patients who are Child-Pugh class A with no esophageal varices because of the associated bleeding risk.

Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab is the first regimen to demonstrate improved overall survival compared to sorafenib. The combination employs two monoclonal antibodies with complementary mechanisms of action to deliver a one-two punch against HCC. Atezolizumab, an anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) therapy, targets a protein produced by cancer cells that makes them undetectable to the immune system’s T-cells, while the anti-VEGF therapy bevacizumab slows the growth of blood vessels that support tumors.

The FDA approved the combination based on the results of the phase 3 IMbrave 150 trial, which demonstrated a 42% reduction in the risk of death and a 41% reduction in the risk of progression compared to sorafenib. Objective response rates were 27.3% for atezolizumab-bevacizumab and 11.9% for sorafenib, while 18 patients had complete response to the combination. No patient in the sorafenib arm demonstrated complete response.

Overall survival at 12 months was 67.2% among patients receiving the new combination, vs. 54.6% for those receiving sorafenib. Progression free survival also improved, from 4.3 months for sorafenib to 6.8 months for atezolizumab-bevacizumab. The trial enrolled 501 treatment-naïve patients with locally advanced, metastatic, or unresectable HCC.1

Updated results with an additional 12 months of follow-up presented at the 2021 Digital Liver Cancer Summit showed even better outcomes, with median overall survival of 19.2 months for atezolizumab-bevacizumab vs. 13.4 months for sorafenib. Progression free survival rose to 24% for the combo vs. 12% for sorafenib. Response increased over time as well. Thirty percent of those receiving the combination experienced an objective response compared to 11% for sorafenib and 7.7% in the combo arm had a complete response compared to less than 1% of those on sorafenib. The updated findings showed benefit even in patients with high-risk disease.

Four other drug combinations are in phase 3 trials, with results expected shortly. “A combination of an immunotherapy and a targeted therapy, is basically the future of oncology right now,” Fields said. “We’re looking at how best to use these agents together.”

- Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915745