Not all casualties of the COVID-19 pandemic occurred because of infection with the virus. One group on which it had disastrous effects were patients with opioid use disorder. In fact, nationwide, the pandemic and related restrictions increased their number to record levels. In response, the VA put a variety of initiatives in place, including making sure that veterans on medication-assisted treatment were able to continue despite shutdowns.

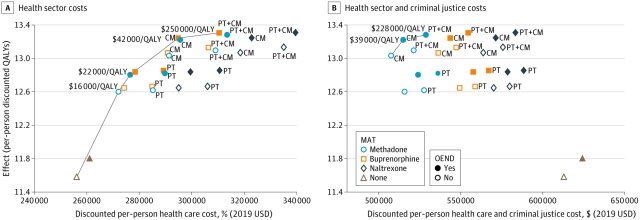

Cost-effectiveness Analysis for US Population with Opioid Use Disorder Results are presented for health sector costs (A) and for health sector and criminal justice costs (B). Currency is reported in 2019 values. CM indicates contingency management; OEND, overdose education and naloxone distribution; MAT, medication-assisted treatment; PT, psychotherapy; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

DALLAS — Drug overdose deaths rocketed to previously unseen levels as the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the United States through 2020, and veterans weren’t spared.

Many factors played a role in the spike, including increased substance use, anxiety and depression exacerbated by the pandemic, economic shock, extended social isolation, erratic supply of illicit drugs and disruption of treatment programs. For veterans battling addiction, the combination made staying sober—and alive—even harder.

Nationally drug overdose deaths rose from 70,630 in 2019 to a projected 90,000 in 2020, setting a record for annual deaths and posting the largest single-year increase in the past two decades, according to the Commonwealth Fund. Of the deaths in 2019, 70% were attributable to opioids.

COVID-19 “also has increased the number of people with opioid use disorder (OUD) that do not receive any form of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), with methadone, buprenorphine, or extended-release naltrexone—or overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND),” researchers with the VA’s Health Services Research & Development group found in a study published in JAMA Psychiatry.1

Even among individuals who had begun treatment prior to March 2020, “[t]he pandemic caused some persons with opioid use disorder to experience disruptions in treatment and recovery services as well as potential loss of informal social support,” a recent article in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report noted.2

A reduced number of veterans initiating medication-assisted treatment and disruption in therapy among those who had previously begun treatment arose from the closure of clinics, postponement of non-COVID-19-related services and a switch to telemedicine for the provision of most care through the VA.

Most Vulnerable

For those at greatest risk of both COVID-19 and negative consequences of substance use, such as homeless veterans and veterans in assessment and recovery centers, quarantine centers and alternate care sites, the VA recently released “A Clinical Resource Guide for Community Care Centers During the COVID-19 Pandemic” that reflects their needs and lays out recommendations for care. Developed under the supervision of Dina Hooshyar, MD, MPH, director of the VA’s National Center on Homelessness among Veterans, based in Dallas, and Barbara DiPietro, PhD, senior director of policy for the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, headquartered in Nashville, TN, the guide aims to reduce the risks posed by the pandemic to individuals “who are experiencing homelessness or have complex medical and social service needs.”

The guide encourages treatment of veterans and others with substance use disorder and is clear about the best options for treatment in the current environment of a continuing pandemic. “While a substance use disorder is a chronic disease, it is treatable. Like other medical concerns, individuals respond differently when beginning treatment.”

For alcohol use disorder, the guide encourages considering medications as part of a comprehensive treatment approach as they reduce cravings and prevent relapse. Medications recommended include oral and extended-release injectable naltrexone, acamprosate, topiramate and disulfiram, though a nationwide shortage of disulfiram makes one of the other drugs a better choice currently.

Veterans seeking care or housing at a center during the pandemic who have an opioid use disorder “may be using at higher rates or may return to use after a period of abstinence and as a result be an increased risk for an accidental overdose,” according to the guide. Consequently, centers are advised to engage residents in opioid use disorder treatment as part of a long-term strategy to prevent future overdoses.

“Medications exist to reduce the risk of overdose and all-cause mortality. They are strongly recommended as first-line treatments,” the guide notes. The medications for opioid use disorder include buprenorphine/naloxone, long-acting injectable form of buprenorphine, extended-release injectable naltrexone, and methadone. Because of the challenges created by the pandemic, “at the current time, it is recommended that providers consider office-based outpatient treatment using buprenorphine/naloxone or extended-release injectable naltrexone in lieu of referral to an opioid treatment program for methadone,” the authors said.

Veterans who cannot regularly receive medications in an office or outpatient setting or would be more successful in recovery if they didn’t need to take a pill every day may have long-acting naltrexone administered at retail pharmacies at major grocery stores, including Albertsons, Acme, Jewel-Osco, Pavilions, Randalls, Safeway, Tom Thumb, Shaw’s, Star Markets and Vons. The long-acting injectable aripiprazole lauroxil can also be obtained through these outlets for individuals on therapy for schizophrenia, a mental health disorder that occurs more often among this population.

The VA’s HSR&D study on medication-assisted therapy found that treatment with methadone reduced overdoses an estimated 10.7%, while treatment with buprenorphine or naltrexone cut the risk 22%. Overdose deaths declined 6% with methadone, 13.9% with buprenorphine or naltrexone. Healthcare and criminal justice costs were reduced by $25,000 to $105,000 in lifetime costs per person with medication, with similar results seen in VHA patients as in the wider U.S. population of individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD).

In a comment on the JAMA Psychiatry study, Noah Capurso, MD, MHS, of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System and Yale University School of Medicine’s department of psychiatry, argued that the effectiveness of the medications used in opioid use disorder is such that the phrase “medication-assisted treatment” should be banished. These medications “do not assist any more than insulin assists the treatment of Type 1 diabetes. Both of these conditions may benefit from ancillary interventions, … but there is no ambiguity that insulin is the primary treatment for Type 1 diabetes, and there should not be ambiguity in the case of medications for OUD either.”

- Fairley M, Humphreys K, Joyce V, Bounthavong M, Trafton J, Combs A, Oliva E, Goldhaber-Fiebert J, Asch S, Brandeau M, and Owens D. Cost-Effectiveness of Treatments for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. March 31, 2021; online ahead of print.

- Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, Post LA, Feinglass JM. Notes from the Field: Opioid Overdose Deaths Before, During, and After an 11-Week COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:362–363. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3