What Is the Significance of Young Vs. Late Onset CRC?

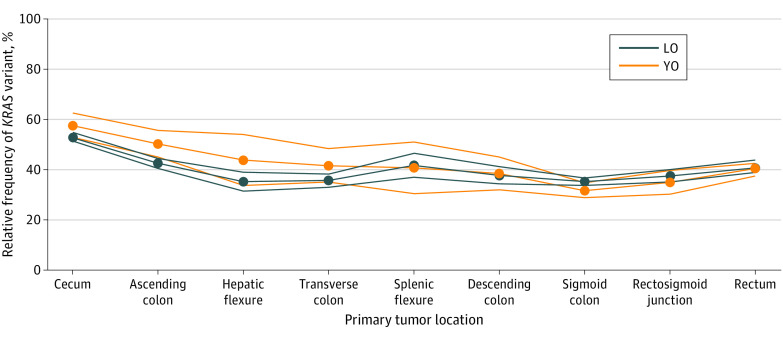

Click to Enlarge: KRAS Variant Distribution by Anatomical Site

LO indicates late onset; YO, young onset. Source: JAMA Network Open

PALO ALTO, CA — Since 2010, KRAS molecular testing has been guideline-recommended in the VA healthcare system. The goal has been to help determine how metastatic cancer is likely to respond to anti-EGFR drug therapy.

Demographic changes in colorectal cancer incidence have prompted researchers to ask further questions, including how the prognostic profile of KRAS sequence variation compares between patients with young-onset and late-onset colorectal cancer.

Albert Y. Lin, MD, MPH, an oncologist at the VA Palo Alto, CA, Medical Center, is the corresponding author on the cross-sectional study of 21,661 patients with colorectal cancer. It found that KRAS sequence variation was associated with worse survival, compared with KRAS wild type in patients with both young- and late-onset cancer. The median cause-specific survival for KRAS variant vs. KRAS wild type was 3.0 and 3.5 years in young-onset and 2.5 vs 3.4 years in late-onset cancer, according to the report in JAMA Network Open.1

“These findings may provide additional clarity into the association between KRAS sequence variants and clinical outcomes and between KRAS status and age of colorectal cancer onset,” the authors wrote, pointing out that the association between KRAS sequence variation status and clinical outcomes in CRC has evolved over time.

The goal was to characterize the association of age at onset, tumor sidedness, and KRAS sequence variation with survival among patients diagnosed with CRC.

Data was extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and included patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum from 2010 through 2015. Participants were classified as having young-onset (YO) cancer, if diagnosed between ages 20 to 49 years, and late-onset (LO) cancer, if diagnosed at age 50 years or older. Data were analyzed from April 2021 through August 2023.

The mean age of the patients with KRAS sequence variation status was 62.50, and 45.2% of them were female. Of those, 3,842 patients had YO CRC, including 1,546 with KRAS variants, and 17,819 patients had LO CRC, including 7,311 with KRAS variants.

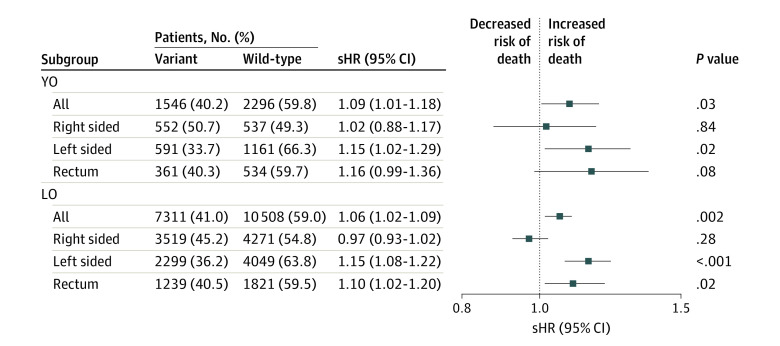

“There was a significant difference in median CSS time between patients with variant vs. wild-type KRAS (YO: 3.0 years [95% CI, 2.8-3.3 years] vs. 3.5 years [95% CI, 3.3-3.9 years]; P = .02; LO: 2.5 years [95% CI, 2.4-2.7 years] vs 3.4 years [95% CI, 3.3-3.6 years]; P < .001),” the researchers pointed out. “Tumors with variant compared with wild-type KRAS were associated with higher risk of CRC-related death (YO: sHR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.01-1.18]; P = .03; LO: sHR, 1.06 [95% CI, 1.02-1.09]; P = .002).

“Among patients with YO cancer, mortality hazards increased by location, from right (sHR, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.88-1.17) to left (sHR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.02-1.29) and rectum (sHR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.99-1.36), but no trend by tumor location was seen for LO cancer.”

They added that, in YO cancer, variant KRAS-associated mortality risk was higher in distal tumors than proximal tumors.

Click to Enlarge: Multivariable Analyses for Colorectal Cancer–Specific Survival Performed Separately by Age of Onset

Competing risk analyses were performed separately by age of onset and also under each age subgroub by tumor location to compare variant vs wild-type KRAS among patients with YO (young-onset; diagnosis at ages 20-49 years) and LO (late-onset; diagnosis at age ≥50 years) cancer. sHR indicates subdistribution hazard ratio. Source: JAMA Network Open

CRC is the third-most-common cancer in the United States, and the second-leading cause of cancer-related death behind lung cancer, according to the article, which advised that overall mortality has declined annually since 1990, partly due to the advent of screening modalities and improvement in treatments.

“In contrast to this overall decline in mortality, there was a recent increase in CRC incidence and deaths among adults diagnosed at younger than age 50 years (young-onset [YO] CRC),” the study team explained. “Moreover, some unique features among patients with YO CRC garnered attention, emphasizing distinct demographic, clinical, histologic, and molecular profiles compared with patients with CRC onset at age 50 years or older (late-onset [LO] CRC) in several notable ways.”

Those include that, clinically and histologically, younger onset CRC patients have a higher risk of poorly differentiated tumors and anaplastic tumors and display mucinous and signet ring cell histology, according to the authors. Disturbingly, they wrote, “These tumors were also more likely to present more distally and at advanced stages. As a consequence of these features, in 2020 the American Cancer Society lowered the recommended age to start screening from 50 to 45 years for individuals at the mean level of risk.”

The underlying cause of the increasing incidence of YO colorectal cancer remains unknown, however.

Previous studies have examined differences in KRAS variants between younger and older patients. “Of common genetic alterations seen in CRC, KRAS variants were of particular interest because of their frequency (approximately 50% incidence in metastatic CRC) and because they carry treatment implications; their presence was associated with resistance to treatment with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor medications, such as panitumumab and cetuximab,” the researchers noted.

The question of whether a KRAS variation was independently associated with prognostic mortality profiles has become more complex and controversial topic with increased testing availability. “Specifically, the presence of KRAS variants in CRC had been theorized to independently associate with adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote. “However, we hypothesize that this association may depend on other variables, such as the specific sequence variation, tumor location, and possibly age of onset.”

KRAS Variants and Clinical Outcomes

The relationship between KRAS variants and clinical outcomes has remained somewhat unclear, they advise, because studies have disagreed on whether all—and which—KRAS sequence variations were associated with inferior survival and/or shorter time to relapse.

Some studies have suggested that KRAS sequence variation was more likely to occur proximally, including a 2015 analysis demonstrating that KRAS variants in tumors occurring distally were independently associated with mortality. The unique association of tumor location, KRAS status, and death was confirmed in a population-based study in 2020.

Because the prevalence of the variations can vary by age of onset. “Therefore, distinctions in KRAS sequence variation rates between YO and LO cancers may carry complex implications for prognosis, treatment strategies, and perhaps even screening recommendations,” according to authors of the current study.

“In this study, our objectives were to assess the interplay among age at CRC onset, tumor location, and KRAS variant status and their collective association with CRC survival time and mortality using a population-based data set,” they clarified, “While previous studies have explored the prevalence of KRAS variants in CRC, to our knowledge, our research was the first to delve into the intersection of age of onset, tumor location, and KRAS sequence variation status.”

In the past, the VA has struggled with increasing uptake of KRAS identification, according to a 2021 study led by the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and the VA-New York Harbor Health Care System, both in New York.

The study published in JCO Precision Oncology determined the underuse of KRAS testing in advanced CRC, especially among older patients and those treated at lower-volume CRC centers.2

“We found high rates of potentially guideline discordant underuse of EGFR mAb in patients with KRAS-WT tumors,” the authors wrote. “Efforts to understand barriers to precision oncology are needed to maximize patient benefit.”

The study pointed out that advances in precision oncology, including RAS testing to predict response to epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies (EGFR mAbs) in CRC, extend patients’ lives.

The investigative team conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with stage IV CRC diagnosed in the VA from 2006-2015. Information came from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and 29 commercial laboratories, and researchers performed multivariable analyses of associations between patient characteristics, KRAS testing, and EGFR mAb treatment.

Their results indicated that, among 5,943 patients diagnosed with stage IV CRC, only 1,053 (17.7%) had KRAS testing. Testing rates increased from 2.3% in 2006 to 28.4% in 2013, however. It is unclear whether the rates have continued to increase.

In multivariable regression, older patients (odds ratio, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.32 for ≥ age 85 vs. < 45 years) and those treated in the Northeast and South regions were less likely, and those treated at high-volume CRC centers were more likely to have KRAS testing (odds ratio, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.48 to 3.63).

“Rates of potentially guideline discordant care were high: 64.3% (321/499) of KRAS wild-type (WT) went untreated with EGFR mAb and 8.8% (401/4,570) with no KRAS testing received EGFR mAb,” the authors advised. “Among KRAS-WT patients, survival was better for patients who received EGFR mAb treatment (29.6 v 18.8 months; P < .001).”

But what about KRAS variations that were not wild-type?

A study published in December in the New England Journal of Medicine explained that KRAS G12C (The Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homologue glycine-to-cysteine mutation at codon 12) is a driver mutation that occurs in approximately 3% to 4% of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and often is associated with poor prognosis.

“In patients with disease that is refractory to initial therapies (fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab), the standard late-line treatments—trifluridine-tipiracil or regorafenib—have shown limited efficacy (objective response, 1 to 2%; median progression-free survival, ≤2.0 months) but at the cost of toxic effects,” wrote the international authors. “Currently, no targeted therapies driven by a positive-selection biomarker are approved specifically for the treatment of patients with KRAS-mutated colorectal cancer.”

The study found, however, that sotorasib “selectively and irreversibly inhibits the KRAS G12C protein to block downstream proliferation and survival signaling. Although single-agent KRAS G12C inhibitors (sotorasib and adagrasib) have shown improved outcomes in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with KRAS G12C mutation, KRAS G12C inhibition alone has shown limited activity in patients with colorectal cancer.”

The study explained that treatment-induced resistance selective to KRAS G12C inhibition “develops primarily through upstream reactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway and is supported by the synergistic activity of concomitant KRAS G12C and EGFR inhibition in preclinical models.”

The authors pointed out that dual KRAS G12C and EGFR blockade was designed to overcome treatment resistance in patients with colorectal cancer with KRAS G12C mutation, which is a cohort in which EGFR inhibitors, such as cetuximab and panitumumab, traditionally do not elicit a response.

More recently, In CodeBreaK 101, a recent single-group phase 1b trial involving patients with chemorefractory colorectal cancer with mutated KRAS G12C, the confirmed response rate was 30% with sotorasib–panitumumab as compared with 9.7% with sotorasib monotherapy, the researchers advised.

“In the past several years, an emphasis has been placed on strategies to better characterize the associations between doses of targeted therapies and the efficacy and safety of such doses in order to inform dose selection and maximize efficacy while minimizing toxic effects,” they added. “Comparisons between the recommended phase 2 dose and lower dose levels are an important part of the dose-selection process. The recommended phase 2 dose of sotorasib is 960 mg once daily. A lower dose, 240 mg once daily, is being tested because of the nonlinear pharmacokinetic properties of sotorasib.”

The study team conducted the international phase 3 CodeBreaK 300 trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of two different doses of sotorasib (960 mg and 240 mg) in combination with panitumumab. That was compared to the investigator’s choice of standard-care therapy (trifluridine-tipiracil or regorafenib) in patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer with KRAS G12C mutation.

The authors concluded that, in the phase 3 trial of a KRAS G12C inhibitor plus an EGFR inhibitor in patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer, “both doses of sotorasib in combination with panitumumab resulted in longer progression-free survival than standard treatment. Toxic effects were as expected for either agent alone and resulted in few discontinuations of treatment.”

- Aljehani MA, Bien J, Lee JSH, Fisher GA, Lin AY. KRAS Sequence Variation as Prognostic Marker in Patients With Young- vs Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2345801. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.45801

- Becker DJ, Lee KM, Lee SY, Lynch KE, Makarov DV, Sherman SE, Morrissey CD, Kelley MJ, Lynch JA. Uptake of KRAS Testing and Anti-EGFR Antibody Use for Colorectal Cancer in the VA. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021 Apr 13;5:PO.20.00359. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00359. PMID: 34250412; PMCID: PMC8232805.

- Fakih MG, Salvatore L, Esaki T, Modest DP, et. Al. Sotorasib plus Panitumumab in Refractory Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. N Engl J Med. 2023 Dec 7;389(23):2125-2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2308795. Epub 2023 Oct 22. PMID: 37870968.