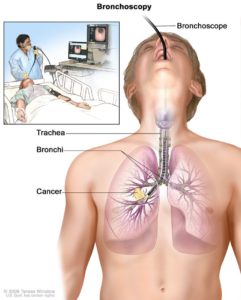

Bronchoscopy. A bronchoscope is inserted through the mouth, trachea, and major bronchi into the lung, to look for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a cutting tool. Tissue samples may be taken to be checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

INDIANAPOLIS — Recognizing the substantially greater risk for lung cancer faced by veterans, the VA has aggressively ramped up its screening program to reach those at-risk wherever they are. A key component of the strategy is the Partnership to Increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS).

Established in 2017 with a $7 million grant from an industry foundation, $3.4 million from the Office of Rural Health, in collaboration with the VA’s Center for Strategic Partnerships and the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program, VA-PALS has since expanded to 17 VAMCs and a growing number of affiliated organizations, including the GO2 Foundation and its more than 700 member screening Centers of Excellence network. Together, the participating institutions have screened more than 19,000 veterans.

The VA continues to add VA-PALS screening locations. Today, they include VAMCs in Atlanta; Baltimore; Birmingham, AL; Chicago; Cleveland; Columbus, OH; Denver; Houston; Indianapolis; Kansas City, MO; Louisville, KY; Milwaukee; Nashville, TN; Philadelphia; Phoenix; Prescott, AZ; St. Louis; and Wichita, KS. Each of the VAMCs in PALS has a physician site director, thoracic radiologist and an advanced practitioner lung screening navigator leading their screening program. All the centers offer advanced diagnostic services and treatment options including minimally invasive thoracic surgery, stereotactic radiotherapy, and medical oncology as well as smoking cessation programs and case management services.

With the GO2 Foundation screening sites, VA-PALS has locations in all 50 states, “but nine of the 12 states with the highest proportions of rural veterans still have three or fewer total [lung cancer screening] facilities,” a study found earlier this year.1

Reaching More Veterans

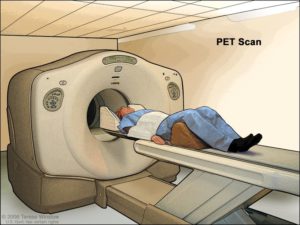

PET (positron emission tomography) scan. The patient lies on a table that slides through the PET machine. The head rest and white strap help the patient lie still. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into the patient’s vein, and a scanner makes a picture of where the glucose is being used in the body. Cancer cells show up brighter in the picture because they take up more glucose than normal cells do.

The VA is determined to correct the geographic mismatch, starting in one of the regions with the highest population of veterans—the Southeast. Funding from the VA Lung Precision Oncology Program is bringing the screening program to smaller VA facilities in more rural areas in the South through a collaboration with the Medical University of South Carolina Hollings Cancer Center. “While the larger VA medical centers can offer screening and access to medical oncologists and precision oncology trials, there are many veterans serviced by smaller VA medical centers who have not had access to screening,” said Nichole Tanner, MD, a pulmonologist and co-director of Hollings’ Lung Cancer Screening Program and co-lead of the expansion project.

In cooperation with the Atlanta and Birmingham VAMCs and their National Cancer Institute affiliates, the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center in Birmingham and the Emory Winship Cancer Institute in Atlanta, Tanner and her colleagues aim to expand access to screening to veterans in Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina.

In South Carolina, the team is training the staff at the Columbia VAMC and its outpatient clinics in best practices for screening. They also are talking with the VA’s Office of Rural Health about testing a mobile lung cancer screening program to reach even more veterans.

“Being in the Southeast, we’re in the tobacco belt, where there’s a high prevalence of lung cancer and lung cancer deaths,” said Tanner. “I’m excited to work with other VA medical centers in our regional network that have great cancer center affiliates in disseminating best practices for lung screening, early detection and opening up lung cancer trials across our three states that stand to benefit and reach more veterans.”

The VA also granted $5 million to the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Massey Cancer Center to implement a lung cancer screening and precision oncology program within the Central Virginia VA Health Care System over the next five years.

“Approximately 40% of veterans are African American, and 60% live in a rural setting; this grant funding fills a critical gap in care for veterans in central Virginia and beyond,” said Bhaumik Patel, MD, co-principal investigator of the program, chief of hematology-oncology at the Richmond VAMC, member of the Developmental Therapeutics research program at Massey and associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at the VCU School of Medicine.

Saving Lives One at a Time

Similar projects are planned or in process across the country. “The project is bringing lifesaving screening to veterans every single day,” said Drew Moghanaki, MD, MPH, a radiation oncologist with the Los Angeles VAMC and professor and chief of Thoracic Oncology at the University of California-Los Angeles Department of Radiation Oncology. “Our goal is to ensure that every veteran who is eligible for lung screening has the opportunity for this lifesaving test, regardless of where they live.”

For many of those veterans, the program has proved lifesaving. Veteran Bobby Richardson was one of the more than 1,900 veterans screened at the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC in Indianapolis since 2019. While finding out he had Stage 1 lung cancer wasn’t the screening outcome he wanted, Richardson is more than happy with the result of finding his cancer early when treatment can cure the disease. The screening allowed Richardson to avoid the outcome of many of his family members—several aunts had died of cancer, and his brother died of lung cancer shortly before Richardson received his diagnosis.

“My brother didn’t have any symptoms up until the last year before he found out he had lung cancer,” Richardson said. Once he did experience symptoms, he had difficulty getting a diagnosis. “He kept complaining that something was wrong.” After another doctor told Richardson’s brother he was developing emphysema, he went to the VA where he was diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer.

“My experience was pretty positive, because my doctors cured me,” Richardson said. “The thing of it was, I never felt sick, never felt bad. I didn’t even know I had cancer until they told me. I would definitely recommend that other veterans get screened.”

New Recommendations

The VA adopted the March 2021 recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force which call for an annual low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scan for anyone age 50 to 80 who has smoked the equivalent of 20 pack-years and currently smoke or quit smoking within the last 15 years. Pack-years are calculated as the number of packs of cigarettes smoked each day times the number of years smoked, so 20 pack-years could be two packs a day for 10 years or one pack each day for 20 years.

The new recommendations dropped the age for starting screening from 55 to 50, and the number of pack-years from 30 to 20.

“What saved me is the fact that mine was caught early,” said Army veteran Mitchell Caviness. “Get screened. It’s imperative to catch this before it gets to Stage 2 or 3.” For Caviness, his advocacy for screening is a natural continuation of his Army training. “If what I’m saying can help save one veteran’s life, it’s like the 101st Airborne: we leave no man behind.”

- Boudreau JH, Miller DR, Qian S, Nunez ER, Caverly TJ, Wiener RS. Access to Lung Cancer Screening in the Veterans Health Administration: Does Geographic Distribution Match Need in the Population? Chest. 2021 Jul;160(1):358-367. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.016. Epub 2021 Feb 19. PMID: 33617804.

- Tobacco Product Use Among Military Veterans — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:7–12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2external icon.