Click to Enlarge: Most Commonly Prescribed Immunosuppressive Medications and Medical Diagnoses Among Patients Experiencing Drug-Induced Immunosuppression, 2018-2019

HOUSTON — Finding alternatives to steroids in treating inflammatory bowel disease has taken on new urgency with the COVID-19 pandemic.

That and other factors led authors from the San Antonio Military Medical Center, the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, MD, and the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, also in Bethesda, to call for a reduction in use of the drugs for patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

“Despite their ease of use, we always advocate for avoiding or reducing steroid use by our patients,” the authors wrote in the American Journal of Gastroenterology. “This requires detailed conversations in clinic about risks, benefits, and too-often, financial cost. It is difficult to explain to patients (and providers!) why they should avoid therapy that leads to both clinical and endoscopic improvement.”1

According to the VA Whole Health Library, in the U.S. military population, prevalence of IBD is estimated to be 202 and 146 cases out of 100,000 individuals for UC and CD, respectively. The risk is highest in women and those of Caucasian ethnicity but is increasing in minority populations, although incidence is increasing in minority populations.

For decades, corticosteroids, which have powerful anti-inflammatory properties, have been prescribed to treat flare-ups of IBD symptoms, which can be debilitating and include diarrhea, bloody stool, unwanted weight loss, abdominal pain, loss of appetite and fatigue. Although steroids are often effective at inducing remission, they are considered a Band-Aid fix, as the patient’s inflammation and symptoms tend to return when the drugs are discontinued.

In addition, extended use of corticosteroids can lead to additional health conditions, including osteoporosis and hip fractures, cataracts, weight gain, diabetes, muscle weakness, venous thromboembolism and even an increased risk of death. (Compounding the issue, there is no agreed-upon definition of what constitutes a short versus long course of steroid therapy), according to the study.

Steroids also can interfere with clinicians’ ability to diagnose latent or intestinal tuberculosis. Patients who take 0.2 milligrams of prednisone (a common corticosteroid) per day for more than eight weeks are at high risk for developing pneumocystis pneumonia, a serious fungal infection. In fact, steroid therapy puts patients at a higher risk of all kinds of serious infections, a particular concern during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In the middle of the pandemic, the risk associated with steroid therapy has taken on an added urgency,” explained Manreet Kaur, MD, medical director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and associate professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not a listed author on the article. “There’s now data showing a higher mortality—not just morbidity—among COVID patients who’ve been on high doses of steroids. That hasn’t been found with biologic treatments for IBD.”2

Biologics work by interrupting specific inflammation-causing proteins that have been shown to be involved with IBD. These treatments are more precise and targeted than steroids, which affect the whole body, producing a cascade of adverse side effects, according to published reports.

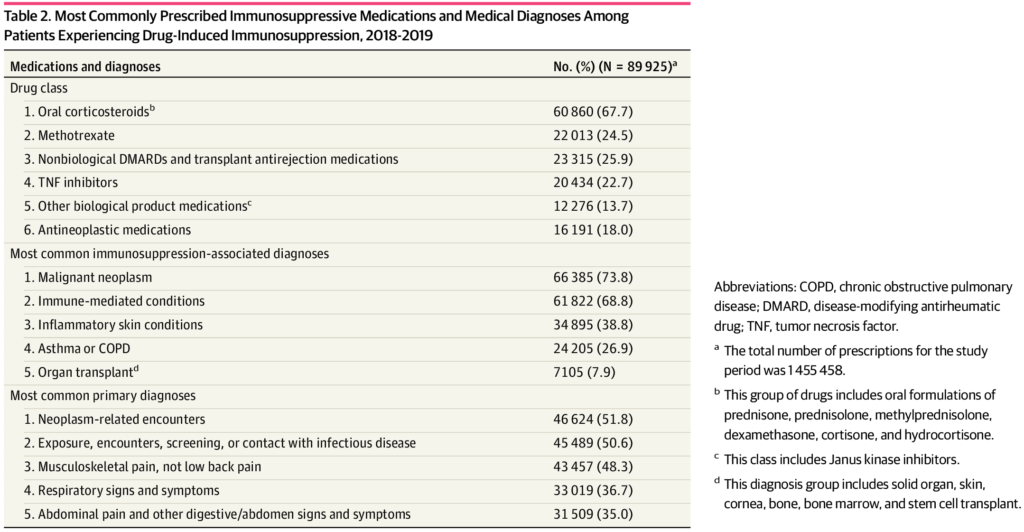

A study earlier this year from researchers at Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor, MI, determined that nearly 3% of insured U.S. adults under 65 take medications that weaken their immune systems.

The study results, published in JAMA Network Open, were based on data from over three million patients with private insurance. They focus on patients’ use of immunosuppressive drugs, including chemotherapy medications and steroids such as prednisone.3

The analysis reveals nearly 90,000 people met the study criteria for drug-induced immunosuppression that may elevate risk for severe COVID-19 symptoms and hospitalization, if they became infected. Two-thirds of them took an oral steroid at least once, and more than 40% of patients took steroids for more than 30 days in a year, according to the report.

20% Receive Steroids

Given these risks, current international guidelines for managing IBD recommend that doctors reduce steroid use among IBD patients in favor of steroid-sparing therapies. Yet, nearly 20% of IBD patients continue to receive multiple courses of corticosteroids as maintenance therapy. There are many reasons for this, the authors argue, chief among them the drugs’ easy availability.

“There’s a familiarity with it, among both providers and patients. They’re inexpensive, and you can get a steroid prescription filled at your local pharmacy with no prior authorization,” Kaur pointed out. In addition, “when there’s a lack of continuity in your care and you’re not on a long-term maintenance therapy, you may be more likely to see physicians who aren’t comfortable with biologics. Patients will start feeling better after a short-term course of steroids, and then they’ll ignore it until they’re ill again, and the cycle continues.”

The authors of the paper outlined four strategies to better equip providers with tools to curb steroid use. First, they argue that steroid therapy can be skipped altogether. In mild cases, the authors recommended topical or oral mesalamine (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) to treat ulcerative colitis or sulfasalazine (a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug) to treat Crohn’s disease. In moderate-to-severe cases, they noted that biologic therapies can induce remission nearly as quickly as steroid therapy.

Second, patients who have been on steroids for more than two months must be tapered off the drugs, they said. As the steroids are discontinued, providers should develop a plan with their patients for how to address symptoms when they return. Third, when steroids are necessary to induce remission, doctors must create a plan to switch patients to another non-steroidal therapy that can effectively maintain remission. This step is key, Kaur said.

“Every time a patient is started on steroids, two things should happen. Number one, there should be a plan to determine the pace at which the patient will be weaned off of them. Number two, there should be a discussion about what these steroids should be a bridge to in terms of a steroid-sparing therapy,” she said. The best time to have this conversation, Kaur argued, is when the steroids are being prescribed. “That’s when patients are most receptive to that message. And it helps get buy-in from the patient to have the conversation early on.”

Lastly, in cases when steroids are a prudent choice, the courses of medication should be short-lived, according to the article, which add that it is imperative that providers educate their patients on the negative effects of steroids and adopt a plan going forward to maintain remission with a nonsteroidal therapy.

“I think the vast majority of patients are unaware of the risk of serious adverse effects associated with steroids. Every time I share that information, it’s almost always met with surprise,” Kaur advised. “Many patients also have a misconception that biologics are riskier than steroids, which they’re not. Biologics have a safer profile by far when it comes to infectious complications than steroids.”

- Harrison N, Humes R, Singla M. Skip, Stop, Switch, and Spare: Steroid Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. Published September 1, 2021. DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001380.

- Brenner EJ, Ungaro RC, Gearry, RB, et al. Corticosteroids, But Not TNF Antagonists, Are Associated With Adverse COVID-19 Outcomes in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Results From an International Registry. Gastroenterology. Published August 2020. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032.

- Wallace BI, Kenney B, Malani PN, Clauw DJ, Nallamothu BK, Waljee AK. Prevalence of Immunosuppressive Drug Use Among Commercially Insured US Adults, 2018-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e214920. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4920