HOUSTON — Disease-modifying therapies have transformed the lives of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) by slowing progression, decreasing relapse rates, and reducing brain lesion accumulation since the first approval of interferon beta nearly 30 years ago.

Despite the large number of clinical trials involving the 19 FDA approved disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS, relatively little is known about how—or whether—race and ethnicity affect patients’ response to the drugs. Given the potential adverse effects and the cost of these medications, better understanding efficacy and tolerability would benefit both patients and the health care system.

Several post hoc analyses of clinical trials indicated that there may be a difference in response to these powerful medications, with some studies suggesting that Black patients did not fare as well on interferons, glatiramer acetate, and natalizumab as white patients who formed the bulk of clinical trial participants.

Carlos A. Pérez, MD, director of the Multiple Sclerosis Regional Program and Neurology Care Line at the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC and assistant professor of neurology at Baylor College of Medicine and John A. Lincoln, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology and director of the MRI Analysis Center at the McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, undertook a study to determine whether those signals were borne out in a more structured analysis.1

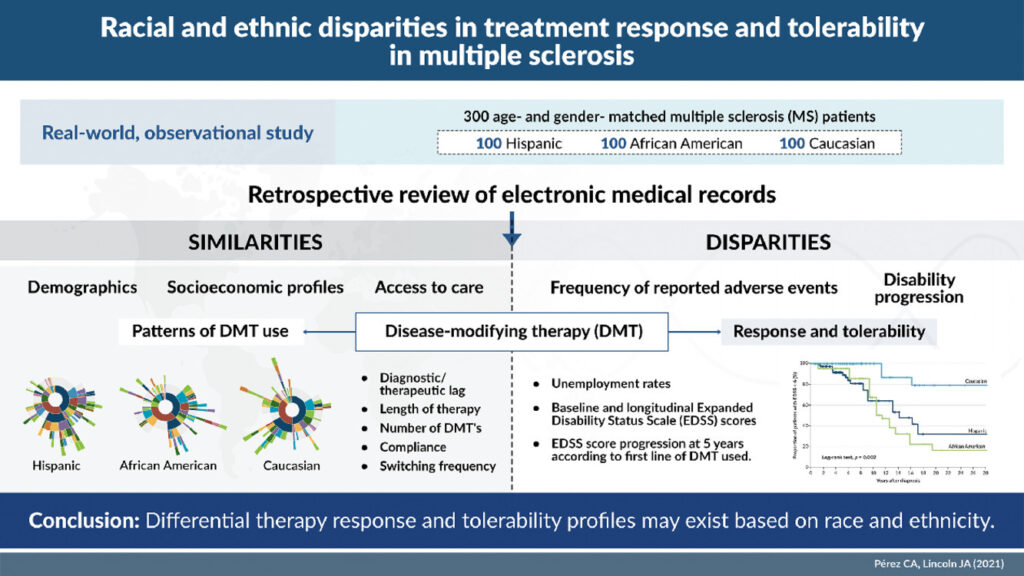

To do so, Pérez and Lincoln matched 100 self-identified Hispanic patients with MS to an equal number of Black and White patients. All patients were treated at a private clinic affiliated with McGovern Medical School, and data were obtained from the MS Comprehensive Care Center’s registry. The registry was screened in February 2021 for patients with a diagnosis of MS who were seen at the clinic between January 2000 and December 2020.

The researchers set as the primary endpoint the proportion of patients with clinical or radiographic evidence of disease activity or Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score progression. A clinical relapse was defined as a new neurological complaint lasting more than 24 hours with objective physical findings or new lesions seen on a follow-up MRI. Secondary endpoints included time from disease onset to ambulatory disability or EDSS 6.0 and EDSS progression five years from diagnosis (sustained increases of 1.0 point for EDSS scores less than 5.5 and 0.5 points for scores of 6.0 or higher). Other secondary endpoints were the odds of developing ambulatory disability based on the first line of DMT used and the reasons for switch or discontinuing treatment.

The study considered monoclonal antibodies and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) inhibitors high-efficacy drugs, while interferons, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, and fumarates were categorized as escalation therapies.

DMT Profile

The three groups had no significant differences in average age at onset, lag in diagnosis or receipt of therapy, treatment duration, disease phenotype, smoking status, education, body mass index or number of comorbidities. There were differences in vitamin D levels, household income and insurance type, but none of these had a significant association with clinical outcome. The groups also did not differ in baseline or current DMT profile. About two-thirds of all three groups proceeded to a second line of therapy during the period studied.

Even with all those similarities, the differences in outcomes were stark. Five years after diagnosis, the overall survival of MS patients who did not have ambulatory disability showed far lower survival times for Hispanics and Blacks than Whites (survival time ratio [STR] 0.17, p = 0.004; and 0.14, p = 0.002, respectively). Black patients had a markedly higher rate of disease progression, as well as adverse events that led to treatment changes or discontinuation.

Hispanic and Black patients also had eight to nine times the risk of ambulatory disability compared to white patients. Black patients accounted for the majority of patients who required therapy escalation and were the least likely to respond to interferon as a first-line therapy. In addition, Black patients had the highest rate of adverse events, which occurred in 46% of cases when Black patients were treated with interferons.

A similar percentage (42.5%) of White patients were unable to tolerate glatiramer acetate, which was particularly notable as 25% more White patients started on glatiramer acetate than Hispanic or Black patients (50.5% vs. 40% and 40.6%, respectively). Patients on CD-20 inhibitors were the least likely to switch therapies across all three groups. Teriflunomide, fumarates, S1P inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies had discontinuation rates of less than 20% across the study groups. Oral medications had higher adherence and lower discontinuation rates than injectables.

Overall, Hispanic patients discontinued therapy at the highest rate (12%). Of the patients switched from escalation therapies to a high efficacy DMT, 40.5% were Black, while 34.3% were Hispanic and 25.2% were white. “Initial treatment with high-efficacy drugs was associated with reduced disability progression as defined by EDSS score increase at 5 years from therapy initiation across racial groups, particularly among Blacks,” Pérez and Lincoln found.

“Our findings suggest that race/ethnicity remains a key determinant of health outcome and disparities, and the unequal burden of disease across racial and ethnic groups may not be attributed solely to variations in environmental lifestyle measures and socioeconomic barriers,” the authors concluded. “Racial/ethnic disparities in treatment outcome create an unmet need to identify tailored, multifaceted approaches to therapy selection in MS.”

- Pérez CA, Lincoln JA. Racial and ethnic disparities in treatment response and tolerability in multiple sclerosis: A comparative study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021 Nov;56:103248. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103248. Epub 2021 Sep 9. PMID: 34536772.