Drug Continues to Be Valuable for Underlying Conditions, However

WASHINGTON — For more than a decade, suicide rates have been consistently higher among veterans than non-veterans, and, since 2005, the suicide rate has risen faster among veterans than it has for nonveteran adults.

That has prompted the VA to make suicide prevention one of its highest clinical priorities, said Ira Katz, MD, PhD, senior consultant for mental health program evaluation at the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Katz and his colleagues for years have questioned whether lithium—a medication with a long history of use for depression and bipolar disorder and a soft recommendation in VA and DOD clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of suicide—could be an effective tool in lowering suicide risk.

Observational studies published over a couple of decades suggested it could, but Katz knew observational studies are subject to bias. “For example, lithium is really dangerous when people take too much and overdose, so it was possible that it looked like lithium was preventing suicide, because psychiatrists and other providers were less likely to prescribe lithium to patients at risk for overdoses,” he said.

The only way to answer the question was through a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. But that, too, had downsides, chiefly getting enough patients recruited—a problem that had plagued other researchers who attempted such studies.

“We figured way back then if anyone could do this study, if anyone could muster the participants, resources and investigators to do it, it would be the VA, so we applied for and were funded to do the study.”

The trial, designed to assess lithium vs placebo augmentation of usual care in veterans with bipolar disorder or depression who had survived a recent suicide-related event, was initiated at 29 VA medical centers in 2015. Participants were randomized to receive extended-release lithium carbonate beginning at 600 mg/d or placebo. The main outcome measure was the time to the first repeated suicide-related event, including suicide attempts, interrupted attempts, hospitalizations specifically to prevent suicide and deaths from suicide.1

Working with providers and suicide prevention coordinators at the centers, the researchers worked to recruit a sufficient number of participants who had survived a recent suicide attempt or those who had other suicide-related behaviors. But they soon discovered that even with the backing of the VA getting the number of patients required for such a trial was daunting.

Katz believes the recruitment difficulties were related in part to the patients themselves—who are often reluctant to seek and fully engage in care—but also to the doctors who treat them. “While some were reluctant because they didn’t want patients on placebo, others were concerned about the risk of overdose or didn’t want the risk of a particular patient being on lithium, so we were kind of walking a tight rope in identifying the patients and providers who were interested in participating.”

After the randomization of 519 veterans—about one-third of the way into recruitment—the trial showed basically no difference between lithium and placebo outcome on a broad range of suicide events and the study was stopped for futility.

The authors sought to determine if lithium augmentation of usual care reduced the rate of repeated episodes of those suicide-related events. Study participants, who had bipolar disorder or depression, all had survived a recent event.

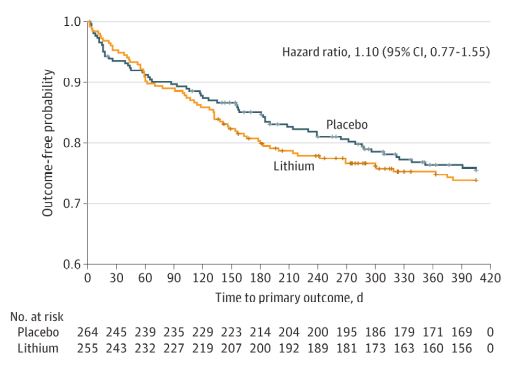

Researchers focused on time to the first repeated suicide-related event, including suicide attempts, interrupted attempts, hospitalizations specifically to prevent suicide and deaths from suicide. The trial was stopped for futility, however, after the veterans were randomized 255 to lithium and 264 to placebo.

“No overall difference in repeated suicide-related events between treatments was found (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.77-1.55),” the authors reported. “No unanticipated safety concerns were observed. A total of 127 participants (24.5%) had suicide-related outcomes: 65 in the lithium group and 62 in the placebo group. One death occurred in the lithium group and three in the placebo group.”

“In this randomized clinical trial, the addition of lithium to usual Veterans Affairs mental health care did not reduce the incidence of suicide-related events in veterans with major depression or bipolar disorders who experienced a recent suicide event,” the study concluded. “Therefore, simply adding lithium to existing medication regimens is unlikely to be effective for preventing a broad range of suicide-related events in patients who are actively being treated for mood disorders and substantial comorbidities.”

Lessons From a Stopped Study

Stopping the study did not imply that lithium was not helpful or more importantly that the study was in vain. In fact, there were some intriguing findings, Katz pointed out.

“During the course of the study, there were four deaths all related to self-harm—one in the lithium and three in the placebo group,” said Katz. While this finding might not be interpretable for this study alone, it might be in combination with other studies on lithium, he said. “Doing a meta-analysis of all the valuable data in our study can contribute to the overall answer to this question.”

The study also gives a picture of how lithium performs—or doesn’t—in real life, said Katz. “The patients are real-life patients. They had not only depression or bipolar disorder, but many had coexisting PTSD and coexisting substance abuse disorder. Many of them didn’t take the medication as directed, and many of them stopped taking medication in the mid-course of the study. So, from a pharmacologic sense, it was kind of a dirty study with a lot of real life in it.

“What we can say as a result is in real-life patients, giving lithium doesn’t have a big effect in preventing a broad range of suicide outcomes,” said Katz. “We think that lithium is valuable, and it may be better than other medications, for example for many patients with bipolar disorder.”

He added the decision of whether to use lithium should probably be based on the value of lithium on the symptoms of bipolar disorder and depression rather than just the possibility it might prevent suicide. “As a result of our study can soften the suggestions about using lithium to achieve a broad range of suicide-related outcomes,” he said, adding that lithium’s role in suicide prevention is one still to be answered.

- Katz IR, Rogers MP, Lew R, Thwin SS, Doros G, Ahearn E, Ostacher MJ, DeLisi LE, Smith EG, Ringer RJ, Ferguson R, Hoffman B, Kaufman JS, Paik JM, Conrad CH, Holmberg EF, Boney TY, Huang GD, Liang MH. Lithium Treatment in the Prevention of Repeat Suicide-Related Outcomes in Veterans With Major Depression or Bipolar Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online November 17, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3170