WASHINGTON — The problem, according to military officials and independent overseers, is not limited to command issues and prosecution of perpetrators but extends to the long-term health and well-being of survivors.

WASHINGTON — The problem, according to military officials and independent overseers, is not limited to command issues and prosecution of perpetrators but extends to the long-term health and well-being of survivors.

Their health is currently compromised by a system that works so poorly to support them that most wish they had not come forward about their experience in the first place, according to reports.

One of the solutions being considered is giving active-duty servicemembers more latitude to seek military sexual trauma (MST)-related care at VA facilities. It’s believed that at VA, survivors might experience less stigma and have less fear of their experience becoming public before they wish it to.

In February, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III established a 90-day independent review commission (IRC) on sexual assault in the military. The IRC was tasked with conducting an independent and impartial assessment of the military’s current treatment of sexual assault and sexual harassment.

The IRC delivered that report in July. Its contents reinforce what survivors and victims’ advocates, as well as many legislators, have been arguing for years: that the military services are not equipped to properly deal with sexual assault and harassment within the ranks. According to the IRC, military culture is permissive of such harassment, perpetrators are ineffectively prosecuted, and victims are frequently shamed, bullied into dropping charges and retaliated against if they go forward with their complaint.

“When it comes to sexual assault and harassment, the IRC concluded that there is a wide chasm between what senior leaders believe is happening under their commands, and what junior enlisted servicemembers actually experience,” the report’s authors stated. “This is true across the enterprise. As a result, trust has been broken between commanders and the servicemembers under their charge and care.”

According to the report, roughly 135,000 active-duty servicemembers have been victims of sexual assault since 2010. It’s estimated that another 509,000 have been the subject of sexual harassment. Those numbers are roughly split evenly between men and women.

LGBTQ servicemembers are assaulted disproportionately, however. A 2018 report found that LGBTQ servicemembers accounted for 43% of sexual assault victims, while making up only 12% of the active-duty force.

The IRC report contained 82 recommendations spanning four lines of effort: accountability, prevention, climate and culture, and victim care and support. The public health framing is present throughout all four areas.

“The department has underinvested in prevention over the years, both at the individual and the unit level,” explained Deputy Secretary for Defense Kathleen Hicks, PhD, at a House Armed Services Subcommittee on Military Personnel hearing last month. “What I think really stands out to me is whether you’re thinking about suicide, self harm or harm to others—it really is a public health approach to understand how to help individuals.”

One of the biggest public health consequences of the military’s failure to properly address sexual harassment is the substantial underreporting. The IRC members use the phrase “no wrong door” throughout the report, describing the idea that a servicemember should be able to safely report their experience through any official channel. However, a legitimate fear of the fallout from reporting keeps many from doing so.

Consequently, many never report or seek treatment, or they wait until they are out of the military before doing so. Servicemembers who experience sexual harassment and assault can suffer long-term health effects such as PTSD, depression, anxiety and suicide.

One of the IRC’s recommendations is to expand victim service options to allow servicemembers to receive physical and mental healthcare related to a sexual assault or harassment at any VA facility while they are still on active duty.

“Stigma is a significant barrier to seeking behavioral health services in the military community because the culture sets the expectation that servicemembers should be able to handle problems on their own,” the report stated. “A major obstacle to survivors of sexual assault seeking long-term support for trauma is the fear of losing benefits or being declared ‘unfit for duty.’”

This stigma can keep servicemembers from seeking care until it is nearly too late.

“The IRC met with multiple survivors who expressed that they had struggled with suicidal ideation, and some who received no mental healthcare until eventually going to the emergency room for attempting suicide,” the report stated.

Currently, servicemembers are allowed to seek care for MST at any of VA’s 300 Vet Centers without a referral. However, they need a referral to receive medical or mental health services at VA’s 171 medical centers or 1,112 outpatient clinics.

According to the IRC, removing that need for a referral would expand servicemembers’ access to the full range of VA’s MST-related services and have a significant benefit on survivors, who could receive care without fear of stigma from their fellow servicemembers. This would be preferential over servicemembers seeking a civilian physician, who is unlikely to have as much experience, either with MST or military culture.

“VA provides higher quality care, including mental healthcare, on many measures, and VA providers are more likely to have military cultural competence and training in evidence-based therapies to PTSD and other conditions that are highly prevalent among sexual assault survivors,” the report stated.

Some DoD officials are critical of the idea of further opening VA care to servicemembers because of VA’s confidentiality policies and the possibility that active-duty troops could be receiving care or have issues that impact their readiness, that their military superiors are unaware of. However, the IRC believes the benefits far outweigh any dangers and are advocating that DoD embrace the idea.

Overall, DoD has accepted the IRC’s recommendations, with Hicks telling the subcommittee, “I am taking a phased approach to developing comprehensive implementation plans across all of these recommendations. Although we are on a fast timeline, our approach is methodical and deliberate. We have no intention of rushing to failure and risking the loss of faith from those who have trusted us.”

Hicks said she’s been given until the end of the summer to create an implementation roadmap.

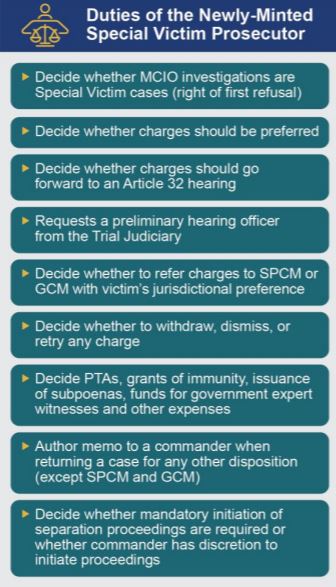

While DoD has previously made efforts to combat sexual assault and harassment within its ranks, this is by far the most concentrated and extensive effort to date, and legislators and advocates who have been pushing for this kind of comprehensive change are cautiously optimistic. Austin and Biden have expressed support for most of the reports’ recommendations, including removing sexual assault cases from the military chain of command and giving them to military prosecutors, as well as adding sexual harassment as an offense in the uniform code of military justice.

The reason for this recommendation is because commanders are untrained in sexual assault law and frequently cited as the source of victim retaliation and the pressure to drop complaints. Removing these cases from the military command structure has long been a goal of reformers—and the area where they have found the most pushback from DoD and conservative lawmakers.