TAMPA, FL — Despite being a “never event” for hospitals, pressure injuries are remarkably common—and deadly. Up to three million Americans experience pressure injuries, and more than 60,000 die just from the hospital-acquired version of these wounds each year.

In an effort to combat the sometimes deadly condition, the has taken a leading role in developing a variety of programs to reduce the incidence of pressure injuries in veterans in VHA hospitals and at home.

Pressure injuries represent localized damage to the skin and underlying tissue. They are typically caused by extended pressure on a point on the body where there is little natural cushion between skin and bone, such as the back of the scalp, ears, shoulder, elbows, lower back, tailbone, hips, knees, ankles and heels. Friction or shear on the skin can also contribute to these wounds, as can excess moisture or dryness.

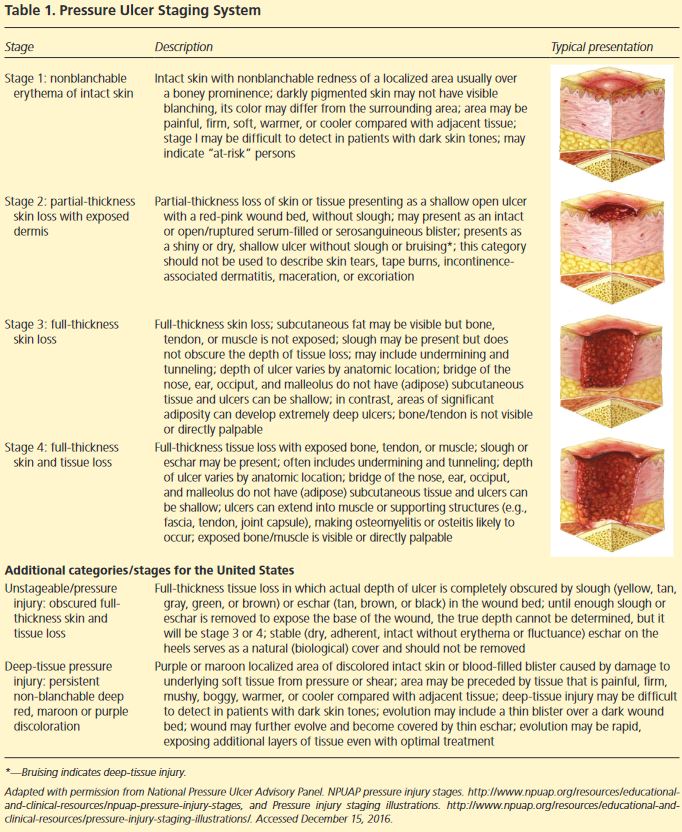

Generally, pressure injuries are divided into four main categories. In stage 1 injuries, the skin remains intact but displays a redness that does not disappear when pressure is applied. Stage 2 injuries have a partial loss of skin with the dermis exposed and a pink or red wound bed. Alternatively, stage 2 injuries could be an intact or ruptured blister. In stage 3 pressure injuries, the patient has incurred loss of the full thickness of skin. Fat tissue, granulation tissue, epibole, and eschar may also be present, but bone, tendons, ligaments, fascia, and other underlying structures are not visible. Stage 4 characterizes wounds were the full thickness of skin and tissue has been lost and fascia, muscle, tendon, ligament, cartilage, or bone is exposed.

Some wounds are difficult to stage because eschar forms a thick scab-like covering over the wound. Such pressure injuries are generally stage 3 or 4. Patients may also present with deep tissue pressure injuries, which feature unbroken skin with deep red, maroon or purple discoloration that does not turn white when pressed or a separation that shows a dark wound bed or blister filled with blood.

Conservative treatment with appropriate bandages and elimination of the source of pressure is typically all that is needed for management of stage 1 and 2 pressure injuries. Stage 3 and 4 injuries, however, pose significantly greater challenges, and often require surgical treatment to close the wound. Surgery may also be appropriate in situations with significant necrosis, osteomyelitis, systemic infection, or declining patient status with chronic non-healing wounds.

Prevention Methods

To reduce the development of pressure injuries, a team led by Lisa Zubkoff, of the VA National Center For Patient Safety at White River Junction, VT, implemented a 12-month Virtual Breakthrough Series Collaborative that used coaching and group calls to educate and motivate nursing teams on best practices in long-term care and acute care settings. The series focused on interventions from the VA’s Skin Bundle, which included employing pressure-relieving surfaces along with new turning techniques, specialized dressings and emollients to help protect skin.

The series proved quite successful. “The aggregated pressure injury rate for all teams decreased from Prework to the Action phase from 1.0 to 0.8 per 1000 bed days of care (P = .01),” the team reported in the Journal of Nursing Care and Quality. “The aggregated pressure injury rates for long-term care units decreased from Prework to Continuous Improvement from 0.8 to 0.4 per 1000 bed days of care (P = .021).”1

Proper Staging

Undertreatment because of misstaged wounds can allow pressure injuries to worsen. To address this issue, a team at the James A. Haley Veterans Hospital in Tampa, Fla., developed a system that used 3D images captured with a camera mounted on a tablet. The wound’s color, geometry, and formation feed into an algorithm that calculates its dimensions.

The system improves on manual processes for evaluation by factoring in characteristics difficult for the eye to ascertain. “That type of measurement can’t accurately account for small improvements or deterioration over the entire surface area, and doesn’t consider changes in the wound’s depth,” said Matthew Peterson, a biomedical engineer who is leading the testing of the computer-based system. “Accurate pressure ulcer measurement is vital for clinicians to accurately assess the severity of the wound and the degree of tissue damage, and to determine whether current treatment strategies are effective.”

More accurate measurements over time allow the care team to tell whether a wound is healing, albeit very slowly, or has stopped improving and requires a different treatment strategy. The semi-automated nature of the system also reduces the time needed to stage and measure a pressure injury.

“This digital technique, which basically captures the whole image rather than just parts of it, is going to provide greater accuracy in measuring the wound,” Peterson says. “We’re capturing the full perimeter and diameter, rather than just having one measurement for length, one measurement for width, and one measurement for depth. Essentially, we aim to determine the size of the wound based on its entire features.”

Healing Promotion

Other groups across the VA have also attacked the problem of pressure injuries for patients with limited mobility. Kath Bogie, MD, of the VA Advanced Platform Technology Center in Cleveland, led a team in development of a “smart bandage” that uses electrical stimulation to promote healing of chronic wounds.2

“As a normal wound heals, there is a lot of biological activity,” Bogie said. “The cells start to proliferate, and the wound begins to heal and close up. A chronic wound gets stuck and doesn’t go on to heal. The general thinking is that electrical stimulation provides the energy to promote healing in a chronic wound.”

While low levels of electricity can disrupt biofilm, minimize infection and promote new blood vessels, two issues have made electrical stimulation unappealing; it typically requires removing the bandage and reapplying stimulation devices before each therapy session. Bogie’s group is developing a multilayer bandage includes an absorbent bottom layer and a removable top layer that incorporates the mechanism that delivers electrical stimulation, temperature sensors, and a smart chip. The bandage that can stay in place for a week and deliver electrical stimulation consistently.

- Zubkoff L, Neily J, McCoy-Jones S, Soncrant C, Young-Xu Y, Boar S, Mills P. Implementing Evidence-Based Pressure Injury Prevention Interventions: Veterans Health Administration Quality Improvement Collaborative. J Nurs Care Qual. 2021 Jul-Sep 01;36(3):249-256. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000512. PMID: 32868734.

- Bogie KM. The Modular Adaptive Electrotherapy Delivery System (MAEDS): An Electroceutical Approach for Effective Treatment of Wound Infection and Promotion of Healing. Mil Med. 2019 Mar 1;184(Suppl 1):92-96. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy276. PMID: 30395273.