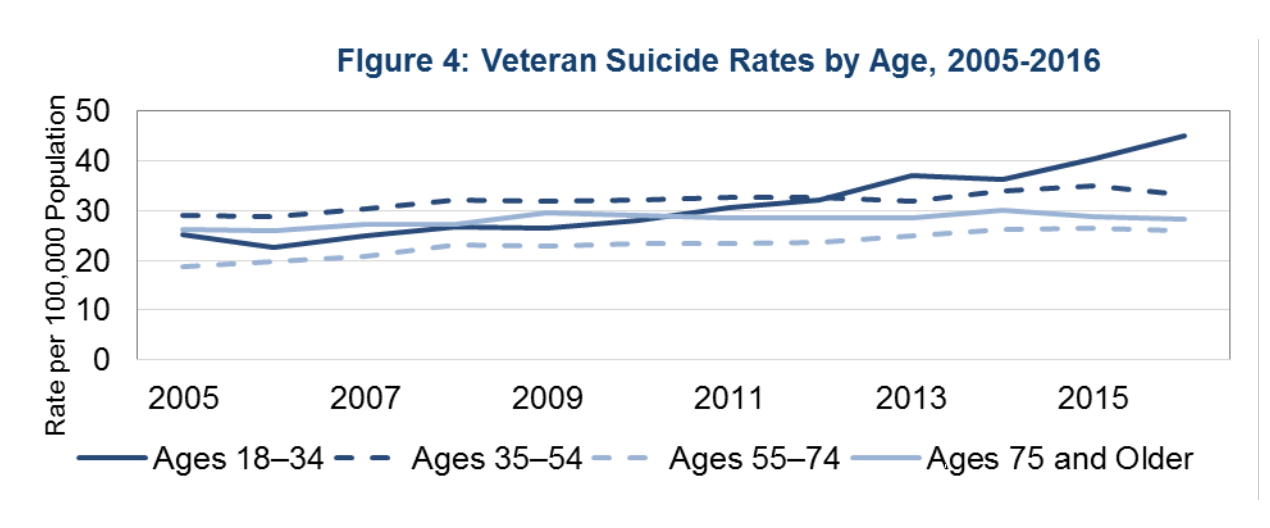

WASHINGTON—Rates of suicide among younger veterans (ages 18-34) “increased substantially in recent years,” climbing from 40.4 suicide deaths per 100,000 population in 2015 to 45 suicide deaths per 100,000 population in 2016, according to a new report.

That information comes from VA’s most-recent analysis of its suicide data from 2005 to 2016 that was released in September. The data, according to the agency, is being used to evaluate and improve its suicide program.

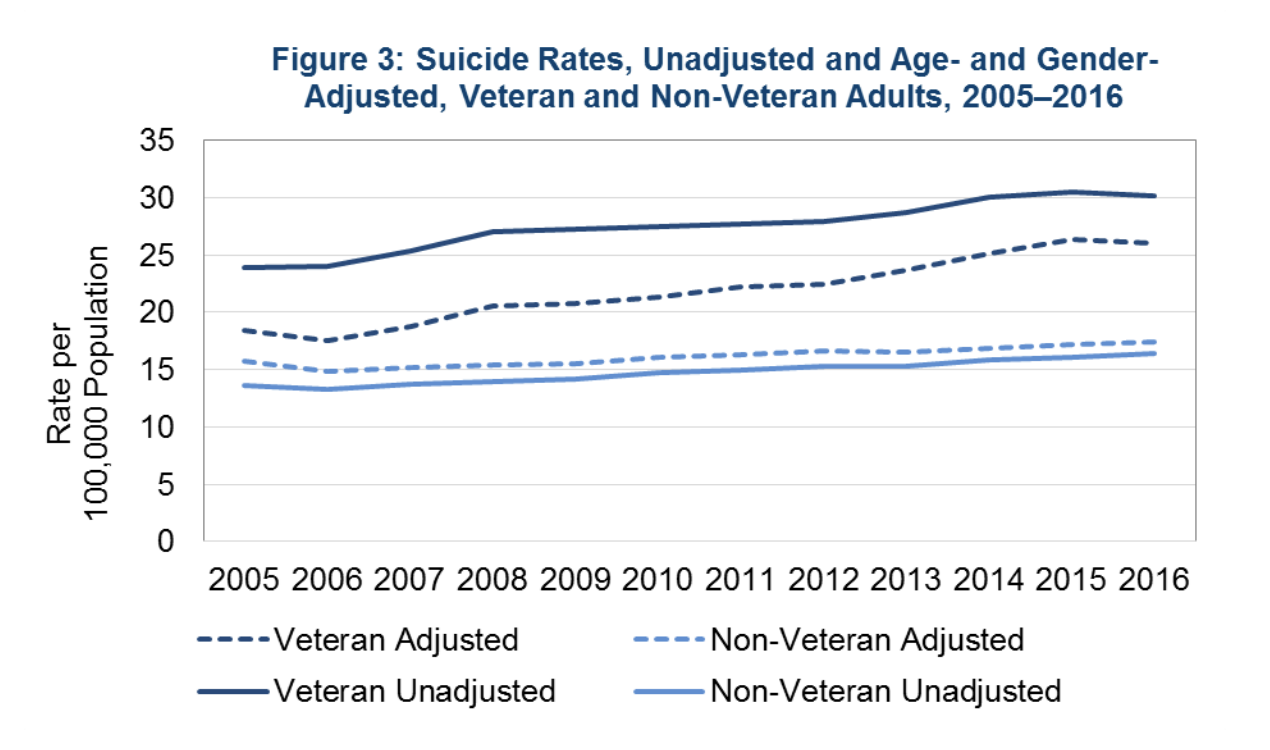

Overall, the number of veteran suicides per year decreased slightly from 6,281 deaths in 2015 to 6,079 deaths in 2016. The rates were lowest among older veterans age 55 and older, which accounted for 58.1% of veteran suicide deaths in 2016.

“To prevent veteran suicide, we must help reduce veterans’ risk for suicide before they reach a crisis point and support those veterans who are in crisis. This requires the expansion of treatment and prevention services and a continued focus on innovative crisis intervention services,” the document noted.

While the report “does not highlight the average number of suicides per day,” the VA explained that, on average, 20 former or current servicemembers die each day by suicide. Of those 20, six have been in VA healthcare and 14 have not.

At a recent House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs hearing on the data, lawmakers lamented that the number of veterans who die each day by suicide has remained roughly the same over time.

“Why is the rate still 20 [a day]?” House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs Rep. Phil Roe (R-TN) asked.

“We are all very concerned about these issues, and I think frustrated and worried about the obstinance of those figures staying where they are despite great effort. … We clearly need to do better, and there are things afoot that we don’t understand yet,” added Rep. Elizabeth Esty (D-CT).

Rep. Julia Brownley (D-CA) speculated that VA hasn’t been able to move “the needle” in part because of widespread vacancies shortages of psychologists and psychiatrists.

“I think, indeed, it has to be a part of the problem,” Brownley asserted.

Pointing out that billions of government dollars have been committed over the years for suicide prevention, Rep. Jack Bergman (R-MI) questioned what was “missing” in the efforts.

“If we continue down the road we are on without seeing significant results, we need to really question is the road we are on the right way.” Bregman said.

‘Beyond Frustration’

VHA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Suicide Prevention National Director Keita Franklin, PhD, responded that she was “beyond frustrated about the numbers and data and that we are not seeing a difference.”

She told lawmakers that the number has remained “regrettably stable since 2008,” adding, “Zero suicides is and must remain our ultimate goal.”

Franklin said the problem might be “dosage.”

“We tend to do a lot of one thing at one time. We will invest in mental health, and we will invest in crisis line work, and we do it very well—full throttle. Preventing suicide takes a broad public health approach, probably a bundled package of about 10 or 12 things at full throttle all the time,” she explained.

Franklin also insisted that, if VA is to be successful in stemming suicides, the agency must be able to keep all veterans from taking their own lives, including those who do not and may never seek VHA care. In June, she pointed out, VA published a comprehensive national veteran suicide prevention strategy that incorporates a range of prevention activities for veterans in the VA healthcare system, as well as those who are not.

“We must think about how to better support veterans well before there is a crisis. We need to find new and innovative ways to deliver the support and care to the entire 20 million veteran population. This philosophy is at the heart of our new public health approach,” she said.

Gregory K. Brown, PhD, director of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine Center for the Prevention of Suicide, underscored the importance of assessing the quality of suicide prevention efforts to see whether the programs actually work, as well as monitoring their implementation.

“If it is successfully implemented, that is great, but we need to monitor how well we implement these programs,” he told lawmakers. “The quality of the implementation matters tremendously. Just like any other medical procedure you do, quality matters. We need to put some resources into measuring quality and then providing additional training to improve quality.”