Study Looks at What Percentage Actually Get Help at VA

PITTSBURGH—Among veterans presenting for first-time care within the VA healthcare system, about 11% meet the criteria for a diagnosis of substance use disorder. Most prevalent among both male and female veterans, in addition to cigarette smoking, is heavy episodic drinking.

In fact, among men 18-25, heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorder were both more prevalent among veterans than civilians, according to an article in the American Journal of Addiction.1

Among the reasons for the higher rates is the effect of co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. The VA has pointed out that more than two out of 10 veterans with PTSD also has SUD and that a third of veterans seeking treatment for SUD also has PTSD.

Further complicating matters, according to the National Center for PTSD, war veterans with PTSD and alcohol problems tend to binge drink, ingesting four to five drinks or more in one to two hours. And the alcohol abuse problems and consequences at the VA aren’t likely to go away soon. Among recent veterans returning from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, about 1 in 10 have a problem with alcohol or other drugs.

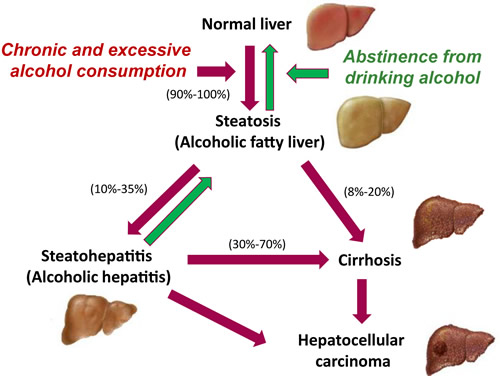

One result is a high rate of medical consequences, with more than 90,000 veterans being treated for cirrhosis of the liver between 2011 and 2015. Perhaps even more surprising is that more than 30,000 of those continued to have a coexisting alcohol use disorder.

Stice CP, Xia H, Wang XD. Tomato lycopene prevention of alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma development. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2018;4(4):211-224. Published 2018 Dec 18. doi:10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.11.001

The International Agency for Research on Cancer found that the population attributable factor for alcohol in hepatocellular carcinoma to be 32% in North America. “The bulk of epidemiological data support alcohol drinking as a major risk for HCC,” according to the American Gastroenterological Association. The AGA noted that, even patients whose cirrhosis is attributable to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis “should abstain from alcohol, because alcohol increases HCC risk, as well as the risk of hepatic decompensation and death from liver disease.”2

A recent study sought to determine if the VA was doing enough to treat those patients. “Despite the significant medical and economic consequences of coexisting alcohol use disorder (AUD) in patients with cirrhosis, little is known about AUD treatment patterns and their impact on clinical outcomes in this population,” wrote the authors from the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and colleagues.3

The VA provides the following types of care to veterans with substance abuse problems:

- First-time screening for alcohol or tobacco use in all care locations

- Short outpatient counseling including focus on motivation

- Intensive outpatient treatment

- Residential (live-in) care

- Medically managed detoxification (stopping substance use safely) and services to get stable

- Continuing care and relapse prevention

- Marriage and family counseling

- Self-help groups

- Drug substitution therapies and newer medicines to reduce craving

The study team said it sought to characterize the use of and outcomes associated with AUD treatment in patients with cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a general term for end-stage liver disease, which can have many causes and which disrupts normal liver tissue and replaces it with scar tissue. Patients with cirrhosis have an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, and most patients with liver cancer already have some evidence of cirrhosis, according to the American Cancer Society.

Included in the retrospective cohort study were veterans with cirrhosis who received VHA care and had an index diagnosis of AUD between 2011 and 2015. Researchers assessed baseline factors associated with AUD treatment—pharmacotherapy or behavioral therapy—and clinical outcomes for 180 days following the first AUD diagnosis code within the study period.

Among 93,612 veterans with cirrhosis, the study identified 35,682 with AUD, after excluding 2,671 who had prior diagnoses of AUD and recent treatment.

Researchers reported that, in the 180 days following the index diagnosis of AUD, 5,088 (14%) received AUD treatment, including 4,461 (12%) who received behavioral therapy alone, 159 (0.4%) who received pharmacotherapy alone, and 468 (1%) who received both behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy.

That appeared to make a significant difference, according to the authors, who explained, “In adjusted analyses, behavioral and/or pharmacotherapy-based AUD treatment was associated with a significant reduction in incident hepatic decompensation (6.5% vs. 11.6%, adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52, 0.76), a nonsignificant decrease in short-term all-cause mortality (2.6% vs. 3.9%, AOR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.57, 1.08), and a significant decrease in long-term all-cause mortality (51% vs. 58%, AOR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.80, 0.96).”

“Most veterans with cirrhosis and coexisting AUD did not receive behavioral therapy or pharmacotherapy treatment for AUD over a 6-month follow-up,” the researchers wrote. “The reductions in hepatic decompensation and mortality suggest that future studies should focus on delivering evidence-based AUD treatments to patients with coexisting AUD and cirrhosis.”

- Rogal S. Youk A. Zhang H. Gellad WF, et. Cal. Impact of Alcohol Use Disorder Treatment on Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With Cirrhosis. Hepatology. First published: 23 November 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31042.

- Loomba R, Lim JK, Patton H. El-Serag HB. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Screening and Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2020 May;158(6):1822-1830. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.053. Epub 2020 Jan 30.

- Teeters JB, Lancaster CL, Brown DG, Back SE. Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:69-77. Published 2017 Aug 30. doi:10.2147/SAR.S116720