Working Together: How the VA and Industry Beat HCV in Five Years

With new highly effective medications able to cure hepatitis C in 95 percent of veterans who take them, the VA sought to treat as many patients as possible with HCV. In 2018, Darrell A. Mason Sr. (center), a patient at the Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital in Chicago, became the 100,000th veterans treated for HCV. The program has continued since then. Photo from April 2, 2018, VAntage Point blog.

WASHINGTON — The VA’s elimination of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infections in veterans ranks as one of the great public health success stories of the past decade. Many factors enabled this extraordinary victory, including the nature of the VA, the timing of a cure, the commitment of leadership, support in Congress and the flexibility of industry partners.

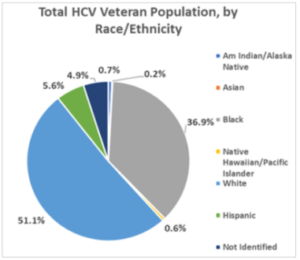

As the nation’s largest integrated healthcare system, the VA has the power to lead and transform care in America. The department’s ability to internally conduct research on a massive scale is unmatched. Its weight in the market has no equal. Critically, VA has more patients with, well, just about any condition. In 2015, it provided care for nearly 175,000 veterans with HCV.

Although HCV infected millions of Americans through blood transfusions and other exposures to infected blood for decades, it was known as non-A, non-B hepatitis until 1989. From the start, identifying the virus, developing a screening test, demonstrating its transmissibility in blood and documenting that it caused hepatitis required a public-private collaboration—one explicitly recognized when scientists at Chiron Corp., the National Institutes of Health and Rockefeller University in New York jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their breakthrough research on HCV in October 2020.

Within two years of its discovery, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for HCV, interferon alpha-2B, but it had only a 6% cure rate. Combining ribavirin with pegylated interferon improved results, but the nearly yearlong duration of therapy and challenging side effects resulted in high rates of discontinuation among veterans.

Starting in 2011, however, the treatment for HCV evolved rapidly. The addition of protease inhibitors to the combination therapy resulted in an approximately 70% cure rate, which rose to 90% as direct-acting antivirals improved. In 2014, the first all-oral, interferon-free treatment emerged, offering greater than 90% of patients sustained virologic response with eight to 24 weeks of treatment. By 2015, the cure rate reached 95% for most patients on a well-tolerated single combination pill, taken once a day for eight to 12 weeks in most cases.

“In 2014, VA began a ground-breaking system of care for veterans with the Hepatitis C virus (HCV). The Food and Drug Administration approved two new, highly effective drugs—Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) and Simeprevir (Olysio)—that work to change the lives of veterans infected with Hepatitis C,” the VA said in its 2018 budget. “VA wants to ensure that all veterans eligible for these new drugs, based on their clinician’s recommendation, receive the medication.”

The list price for the drugs started at $1,000 per pill. Still, for the VA, treatment made financial sense. Unlike other payers, the healthcare system would likely provide care for veterans on its rolls throughout their lives and would incur the cost of liver complications, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplant for a significant percentage of veterans if they were not cured. The cost for the shorter course of drugs was not significantly different than the cost of the nearly one-year course required before DAAs, but nearly everyone could tolerate the new treatment, and virtually all patients achieved sustained virologic response.

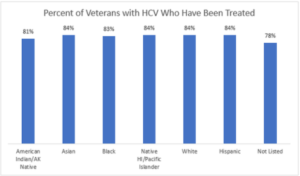

Budget limitations initially led VA to prioritize care for the sickest patients, those who had documented fibrosis, cirrhosis or other complications from HCV. In March 2016, however, the department announced that it was “able to fund care for all veterans with hepatitis C for Fiscal Year 2016 regardless of the stage of the patient’s liver disease. The move follows increased funding from Congress along with reduced drug prices.”

All the manufacturers of HCV therapies—Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Meyers Squibb—worked with the VA to develop pricing that enabled treatment of all veterans. By 2016, the VA was paying about 40% of list price and had rolled out a full screening and treatment program that provided best practices to healthcare systems across the country.

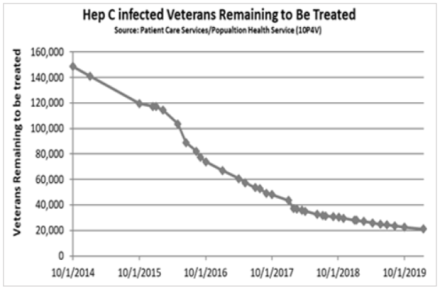

The manufacturers’ flexibility dramatically increased treatment rates in the VA, reducing morbidity and cutting death from advanced liver disease in half. Prior to 2014, 12,000 veterans had achieved sustained virological response to HCV therapies. At its peak, the VA was starting nearly 2,000 veterans each week on HCV treatment.

From January 2014 through the end of fiscal year 2018, more than 152,000 veterans had received treatment with DAAs. Cure rates for the last four years topped 94%.

“As the largest single provider of HCV care in the U.S., this is terrific news because it means we are within striking range of eliminating hepatitis C among veterans under the care of the Veterans Health Administration,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie in March 2019. At that point, fewer than 25,000 veterans with HCV in VA care remained to be treated, and efforts were in place to help them overcome issues that kept many of them from receiving treatment such as for substance use disorder and homelessness.

“These efforts have been nothing short of life-saving for tens of thousands of veterans,” Wilkie noted, “and that’s precisely why VA has made diagnosing, treating and curing hepatitis C virus infection such a priority.”