The Cincinnati VAMC offers telerehabilitation for veterans with neurodegenerative conditions. Occupational, physical and speech therapy services are offered through telehealth as an alternative to in-person care. VA photo

PALO ALTO, CA — The VA has long been a leader in the use of virtual healthcare to improve access to care. When the pandemic caused shutdowns in 2020, virtual care became even more important at the VA, with the percentage of outpatient visits conducted virtually rising from 14% prior to March 2020 to 58% by June.

A report from the VA’s Office of Inspector General pointed out that VA patients with any telehealth encounter increased 181% in the first year of the pandemic, while telephone encounters increased by 211%. As late as a year ago, 30% of outpatient care was still being conducted virtually.

While the majority of this virtual care can be and is conducted by telephone, many researchers are concerned that video-based care—which VA leadership considers the preferred method due to its “potential to provide a more comprehensive experience” —is not uniformly available to veterans.

“The rapid shift to video-based care from in-person care may have exacerbated technology access disparities known digital divide,” Jacqueline Ferguson, PhD, and her colleagues wrote in Health Services Research. “Individuals with technological access barriers may rely exclusively on in-person care. As a result of the shift to video-based care, they may be less able to access health care.”1

“Our study team is interested in studies that will enhance the accessibility, capacity and quality of virtual care that the VA offers veterans,” said Ferguson, a research health science specialist with the VA Palo Alto Health Care System and virtual care core associate investigator with the Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), whose mission is to foster high-value healthcare for veterans. Because maintaining access is a critical priority of VA, they conducted the study to, identify veterans who might benefit from outreach to increase adoption of video care, she said.

The team used data in VA healthcare records to identify veterans who had and had not used video care in the first year of the pandemic—March 2020—February 2021, Ferguson said. Then, among the veterans who had at least one video visit, they calculated how many video visits they each had. “We then looked at the demographic characteristics of veterans who used video care and compared them to those who did not,” she told U.S. Medicine. “We also examined the type of care provided at each visit. For example, was it a primary care visit, a mental healthcare visit or a specialty care visit?”

The results compare the likelihood of having a video visit and then the frequency of having a video visit among Veterans with different demographic characteristics.

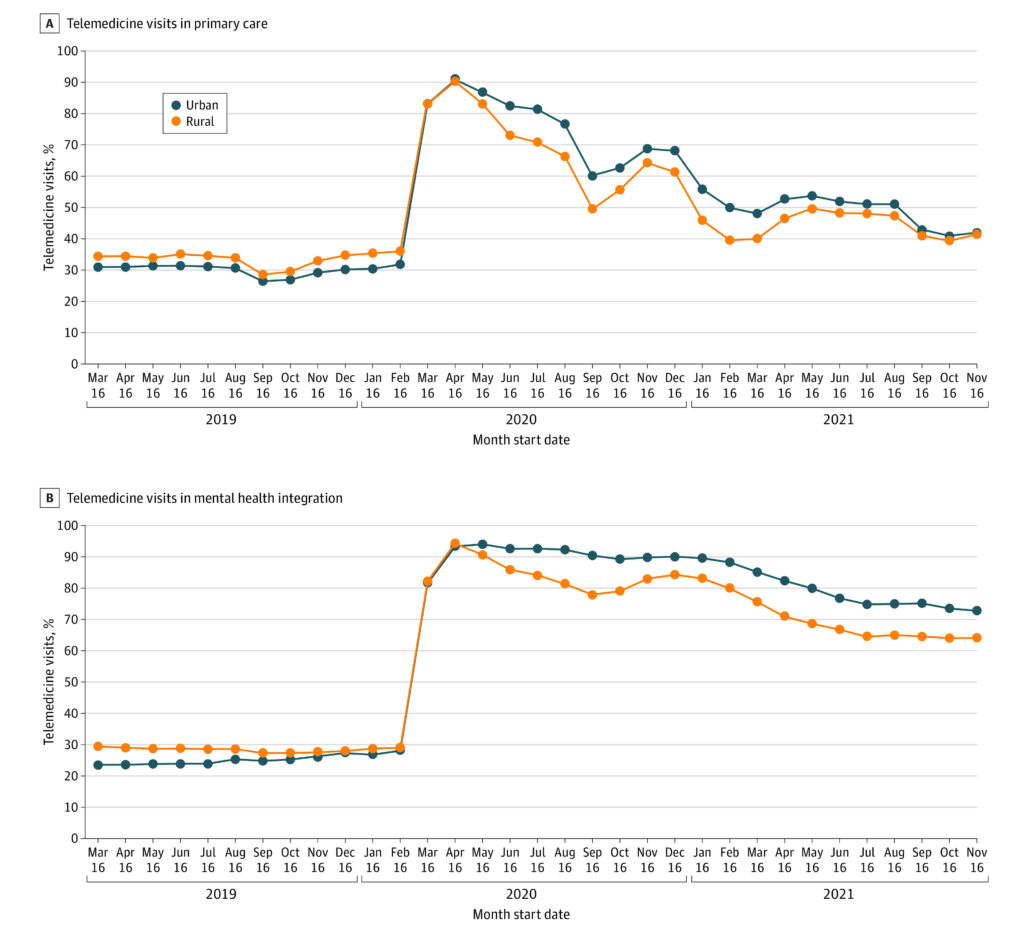

Click to Enlarge: Unadjusted Mean of Monthly Telemedicine and Video Visits for Primary Care and Mental Health Integration Specialties, by Veterans Affairs Health Care System Rurality Over the Study Period Source: JAMA Network Open

“A unique finding was the difference in the frequency of video care use by race,” Ferguson said, adding that the disparities observed likely reflect the unequal conditions in which people live—that is, social determinants of health that might stem from structural racism. “We found American Indian/Alaska Native veterans were less likely to use primary and specialty care health video visits compared to white veterans. Yet, American Indian/Alaska Native veterans who used video-based care had similar frequency of using video care among specialty and primary care”.

“We found similar patterns among veterans with a history of housing instability and among veterans with low-incomes,” she continued. “These findings suggest that, while veterans with certain social circumstances may experience barriers to initial use, or adoption, of video visits, once those barriers are overcome, they have the same rates of use.”

Overcoming Barriers

Ferguson said future work that identifies the reason(s) for this barrier could inform interventions to help initiate a first video visit, and that results of the work have been shared widely within the VA. “We have several interventions underway at VA to help veterans overcome these barriers,” she said. “One of these is the VA tablet program that provides a tablet to veterans who do not have an internet capable device. Giving veterans the tools they need to have a video care visit could be the difference between getting remote care and not.”

While video-based care may inadvertently increase disparities in healthcare access and quality of care, Ferguson noted that the differences her team reported may not necessarily equal a disparity in accessing healthcare—if veterans are accessing care at the levels they need and the way they want (e.g., in-person, phone or video).

“For example, we know that older veterans are less likely to have a video visit than younger veterans. But if an older veteran does not want a video visit and prefers an in-person visit, then their clinician team should focus on providing care in the way the veteran wants to receive care,” she said. “All types of care, both virtual and in-person, should be available via as many different modalities as possible to enable veterans to select the modality of care that meets their needs and that they feel most comfortable with, while providing the highest quality of care.”

Geography might also have created gaps in care. A recent study published in JAMA Network Open pointed out that, while telemedicine can increase access to care, uptake has generally been low among people living in rural areas. The VHA initially encouraged telemedicine uptake in rural areas, but researchers from the VA Los Angeles Health System and the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles and colleagues sought to examine changes over time in rural-urban differences in telemedicine use for primary care and for mental health integration services among VA beneficiaries.2

Their cohort study involved 63.5 million primary care and nearly 4 million mental health integration visits across 138 VA healthcare systems nationally from March 16, 2019, to Dec. 15, 2021. For every system, monthly visit counts for nearly 64 million primary care and mental health integration specialties were aggregated from 12 months before to 21 months after pandemic onset. Researchers categorized visits as in person or telemedicine, including video.

Participants had a mean age of 61.4 and were 90.5% male. The cohort included 66.3% non-Hispanic white patients and 17.2% non-Hispanic Black patients.

Results indicated that, in fully adjusted models for primary care services before the pandemic, rural VA healthcare systems had higher proportions of telemedicine use than urban ones (34% [95% CI, 30%-38%] vs. 29% [95% CI, 27%-32%]) but lower proportions of telemedicine use than urban healthcare systems after pandemic onset (55% [95% CI, 50%-59%] vs. 60% [95% CI, 58%-62%]). That represented a 36% reduction in the odds of telemedicine use (odds ratio [OR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.76), the researchers noted.

They added that the rural-urban telemedicine gap was even larger for mental health integration (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.35-0.67) than for primary care services, adding, “Few video visits occurred across rural and urban healthcare systems (unadjusted percentages: before the pandemic, 2% vs. 1%; after the pandemic, 4% vs. 8%). Nonetheless, there were rural-urban divides for video visits in both primary care (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.19-0.40) and mental health integration services (OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.21-0.56).”

The findings suggested that, even with initial telemedicine gains at rural VA healthcare sites, “the pandemic was associated with an increase in the rural-urban telemedicine divide across the VA healthcare system. To ensure equitable access to care, the VA healthcare system’s coordinated telemedicine response may benefit from addressing rural disparities in structural capacity (e.g., internet bandwidth) and from tailoring technology to encourage adoption among rural users.”

- Ferguson JM, Wray CM, Jacobs J, Greene L, e. al. Variation in initial and continued use of primary, mental health, and specialty video care among Veterans. Health Serv Res. 2022 Nov 7. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14098. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36345235.

- Leung LB, Yoo C, Chu K, O’Shea A, Jackson NJ, Heyworth L, Der-Martirosian C. Rates of Primary Care and Integrated Mental Health Telemedicine Visits Between Rural and Urban Veterans Affairs Beneficiaries Before and After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Mar 1;6(3):e231864. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1864. PMID: 36881410; PMCID: PMC9993180.