Soldiers with the West Virginia Army National Guard’s 753rd Explosive Ordnance Disposal post for a photo during their deployment to Afghanistan. National Guard members don’t have access to the same programs for combat-related alcoholism as active duty servicemembers. Photo by Sgt. Zoe Morris.

PISCATAWAY, NJ — Active-duty servicemembers face well known and quantified risk for alcohol misuse. Consequently, many return from combat to military bases, where they receive screening and have ready access to behavioral health. Those same services are not offered to Reservists and National Guard members who have been deployed, despite even higher rates of alcohol abuse.

In part, the difference in treatment arises from a failure to recognize how much the job of the National Guard has changed in recent decades. Recruiting materials continue to tout the Guard as a one weekend a month and two weeks each summer commitment, with deployments to address natural disasters and other domestic emergencies. For most units, however, preparing for deployment and combat service have become a regular part of the training cycle, necessitating multiple extended weekends and a month of summer exercises.

The extensive training is an outgrowth of the changed mission of the Guard and Reserve, which increasingly calls on units to support American interests and partners abroad. As of late March, the Guard had units all over the globe. Nebraska and Idaho Guard units served in Africa, while members of the Virginia and Kentucky National Guard were stationed in Kosovo and Germany. South Carolina Guard members were in Saudi Arabia; Florida members in Kuwait. Washington units deployed to Poland, and others were preparing to provide support in Eastern and Central Europe in response to the invasion of Ukraine.

More dramatically, recent years have seen units integrated into combat forces. The Guard and Reserve together made up about 45% of the U.S. military forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, but lacked the assessments and reintegration services full-time active duty personnel receive.

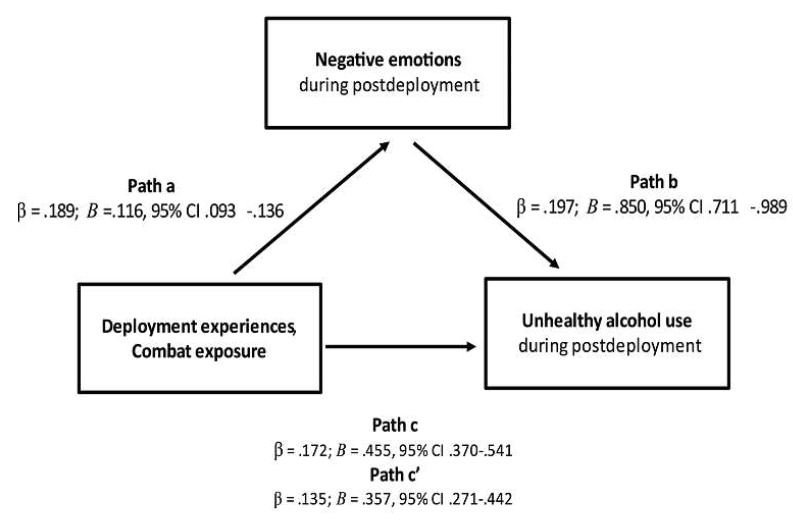

Results of mediation analysis regarding relationships of combat events and negative emotions to postdeployment alcohol use. CI = confidence interval. Source: Griffith J. Postdeployment Alcohol Use and Risk Associated With Deployment Experiences, Combat Exposure, and Postdeployment Negative Emotions Among Army National Guard Soldiers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2022 Mar;83(2):202-211. PMID: 35254243.

“On their return, Guard personnel resume their part-time military service and civilian life and employment,” said James Griffith, PhD, a faculty member and research fellow at the University of Utah’s National Center for Veterans Studies. “Unlike active-duty military personnel, Guard personnel typically do not live near military installations to receive behavioral health care. And many are not eligible for military health care unless conditions are directly related to active-duty military service.”

To better understand the impact of deployment on alcohol use among Guard members, Griffith analyzed survey data from more than 4,567 Army National Guard soldiers who returned from Iraq in 2010. The participants, who represented 50 companies, completed the 80-question Army Reintegration Unit Risk inventory, which included questions on drug and alcohol use, among other topics. Their responses were compared to those of 12,567 National Guard members in 180 company-sized units who were not deployed during the same year.1

Results published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs demonstrated that deployed Army National Guard (ARNG) soldiers had higher rates of heavy drinking than garrisoned Guard members who performed domestic roles—and higher rates than shown in previous surveys of deployed full-time servicemembers. The highest risk of alcohol abuse occurred in the first year after deployment.

Nearly 30% of deployed ARNG soldiers reported heavy alcohol use two to three times a week, vs. 24.1% of those who were not deployed and continued part-time service. Further, the 29.9% prevalence rate of heavy drinking among deployed ARNG “exceeded all rates reported in past studies for deployed personnel (range: 12.5%-26.8%) and nondeployed personnel (7.9% to 18%),” Griffith found. The binge drinking prevalence rate 33.9% among deployed National Guard members was lower than that of nondeployed ARNG and of that seen in deployed active duty forces.

“Specific combat events associated most with postdeployment alcohol use were experiences of combat trauma and engagement in direct combat,” Griffith concluded. On the more positive side, “[t]ime since return was negatively related to postdeployment alcohol use. This might indicate reservists’ gradual reintegration to civilianlike status, providing effective family and community support.”

Greater awareness of the impact of deployment on the mental health and risk of alcohol misuse among National Guard members could go a long way in mitigating some of the negative effects. “Combat events, such as having engaged in direct combat and experienced combat trauma, may precipitate a great deal of personal discomfort (‘moral injury’), necessitating some form of self-soothing, such as excessive alcohol use,” noted Griffith.

He recommended education for returning Guards and Reservists and their families on risks for and indicators of unhealthy alcohol use. Augmented post-deployment services might include regular screening for combat-related trauma and alcohol misuse during the high-risk initial post-deployment year could also identify those at greatest risk and connect them with appropriate behavioral healthcare.

“Given that negative emotions likely play a role in the connection of combat events and alcohol use, some form of screening should assess soldiers’ emotional states,” Griffith added, “and for more severe negative emotions, include referral to psychological health care.”

- Griffith J. Postdeployment Alcohol Use and Risk Associated With Deployment Experiences, Combat Exposure, and Postdeployment Negative Emotions Among Army National Guard Soldiers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2022 Mar;83(2):202-211. PMID: 35254243.