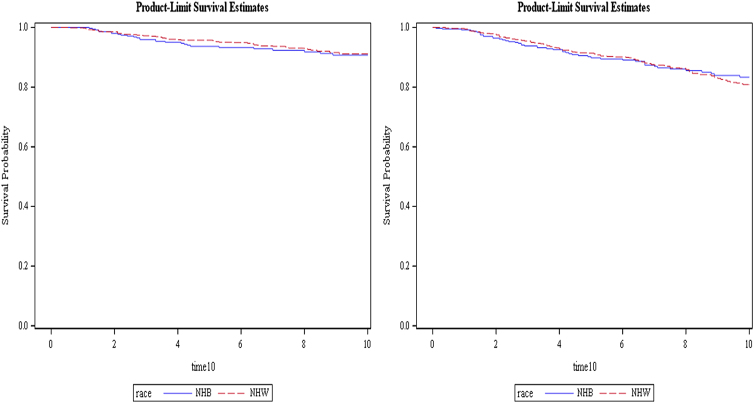

Click to Enlarge: Ten-year breast cancer-specific survival (left) and overall survival (right). Log-rank p-values were 0.6193 and 0.6958 for breast cancer-specific and overall survival, respectively. Five-year survival curves are not shown, however, the p-values were 0.1725 and 0.5062 for breast cancer-specific and overall survival, respectively. Source: National Library Of Medicine

BETHESDA, MD — Though non-Hispanic Black women are more likely to have tumors at a higher grade and later stage and be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, providing quality care can reduce breast cancer survival disparities in these patients when compared to non-Hispanic white women, according to a recent study.

The study published in the journal Health Equity focused on women treated at the Murtha Cancer Center at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, which provides equal-access comprehensive breast care to all active-duty and retired servicemembers and their beneficiaries. The study investigated whether tumor pathology and overall and breast cancer-specific survival differed between non-Hispanic Black women and non-Hispanic white women diagnosed at the cancer center between 2001 and 2018.1

In the United States, breast cancer mortality rates are 40% higher in non-Hispanic Black women than in non-Hispanic white women, with 5-year survival rates reported to be 81% for non-Hispanic Blacks and 91% for non-Hispanic whites. Overall incidence rates were lower in non-Hispanic Blacks than in non-Hispanic whites until the rates converged in 2012. Non-Hispanic Black women are significantly more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age, have higher stage and grade and larger size tumors and be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, according to the study.

This study determined whether equal-access health care reduces unequal breast cancer phenotypes and survival between these racial groups.

The participants, who were enrolled in the Clinical Breast Care Project, had health insurance and were provided multidisciplinary healthcare. They were active-duty, veterans or military beneficiaries ages 18 or older who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer between 2001 and 2018. Only patients who self-described as non-Hispanic Black women and non-Hispanic white women were included in this study.

During the study period, 368 non-Hispanic Black women and 819 non-Hispanic white women were diagnosed with breast cancer at Murtha Cancer Center and qualified for the study. Each person was interviewed to collect data on family cancer and personal health histories, smoking and marital status, and education levels.

A Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated for each patient using comorbidities existing before breast cancer diagnosis. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on the height and weight of the patient at diagnosis.

A dedicated breast pathologist evaluated surgical specimens for each patient and gathered data, including anatomic tumor stage, size, grade and lymph node status. Biomarkers included in the analyses included ER, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), with positivity assigned according to ASCO/CAP guidelines. Patient vital status was collected through Dec. 31, 2020, from electronic health records.

Differences in epidemiological and pathological characteristics between the two racial groups were determined. Overall and breast cancer-specific 5- and 10-year survival rates were compared between races.

The study found that non-Hispanic Black women, compared with non-Hispanic white women, were significantly more likely to have a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2; to have higher grade, later stage tumors with lymph node metastases; and to be hormone receptor negative (HR−)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+) or triple negative.

After adjusting for demographic factors, non-Hispanic Black women remained significantly more likely to have tumors diagnosed at a higher grade and later stage and to be HR−/HER2+ or triple negative. Also, after adjusting for demographic and pathological variables, neither 5- nor 10-year overall or breast cancer-specific survival differed significantly between the racial groups. Breast cancer-specific survival rates were greater than 90% for both non-Hispanic Black women and non-Hispanic white women at five and 10 years.

Less-Favorable Prognostics

The data suggested that survival disparities of non-Hispanic Black women with breast cancer can be lessened with the provision of quality care. Improved survival of non-Hispanic Black women treated at Murtha Cancer Center occurred despite less-favorable prognostics, including tumor pathology differences (higher stage at diagnosis) and higher prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer.

There was no significant difference in the average age at diagnosis: 56.1 years for non-Hispanic Black women and 57.7 years for non-Hispanic white women. Education and smoking status were not significantly different between women in the two racial groups. Non-Hispanic Black women were significantly more likely to have a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2, be unmarried, and have a CCI less than 2, according to the study.

The study advised that all patients seen at Murtha Cancer Center are provided with comprehensive healthcare, regardless of rank or status. Standard coverage includes gynecological examinations with clinical breast examination and annual mammograms starting at 40 years old. All women diagnosed with breast cancer meet with a multidisciplinary healthcare team. Services provided, such as surgery, including breast reconstruction, chemo- and radiation therapies and psychological support, are covered, regardless of the ability to pay.

Future studies that identify the elements of care that led to comparable overall and breast cancer-specific rates of survival between women in the two racial groups are critical to reducing disparities in outcomes not only within the MHS/DoD but also the general U.S. population.

The study had several limitations. Provision of care at Murtha Cancer Center, the only cancer center of excellence within the DoD, might differ from other hospitals within the DoD. It’s unknown whether the lack of disparities detected in the study can be generalized to all patients from MHS and DoD.

The authors also said it is critical to continue monitoring study participants to determine if disparities in survival rates differ significantly after 10 years, especially for women with HR+/HER2− breast tumors. The majority of tumors in both populations were HR+, which have longer times to recurrence (5-20 years) and mortality (≥10-years) than HR− tumors.

Researchers called for future studies to determine whether disparities in quality of life, which were not measured, might exist between breast cancer survivors in these two racial groups.

- Darmon S, Lovejoy LA, Shriver CD, Zhu K, Ellsworth RE. Nondisparate Survival of Non-Hispanic Black Women With Breast Cancer Despite Less Favorable Pathology: Effect of Access to and Provision of Care Within a Military Health Care System. Health Equity. 2023 Mar 10;7(1):178-184. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0128. PMID: 36942312; PMCID: PMC10024578.