Effects Persist Almost a Century Later, VA Study Finds

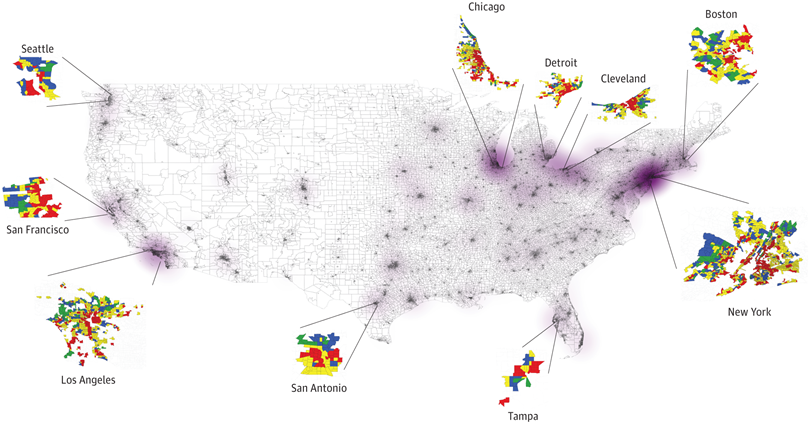

Click to Enlarge: Veteran Cohorts Residing in Historically Home Owners’ Loan Corporation–Graded Neighborhoods Throughout the Continental US. Source: JAMA Network Open

CLEVELAND — The historical practice of redlining, where neighborhoods were graded based on racial and ethnic compositions, has left a lasting impact on the health of communities across the United States.

Created in the 1930s under the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), the color-coded grading system classified neighborhoods as A (best), B (still desirable), C (definitely declining) and D (hazardous), based on foreclosure risk. This practice, research has shown, led to decades of disinvestment in redlined neighborhoods, exacerbating residential segregation and contributing to adverse health outcomes.

A new VA study published in JAMA Network Open has found that, almost a century after this practice was implemented as part of the New Deal, veterans living in lower-graded areas have a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality compared to those living in areas not considered to be a high risk for foreclosure.

In the longitudinal cohort study, U.S. veterans were followed up (Jan. 1, 2016, to Dec. 31, 2019) for a median of four years. Data, including self-reported race and ethnicity, were obtained from VAMCs across the United States on enrollees receiving care for established atherosclerotic disease (coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease or stroke). Using historical maps, the researchers linked redline information to the cohort. The adjusted association between HOLC grade and adverse outcomes was measured using Cox proportional hazards regression. Competing risks were used to model individual nonfatal components of major adverse cardiovascular events.1

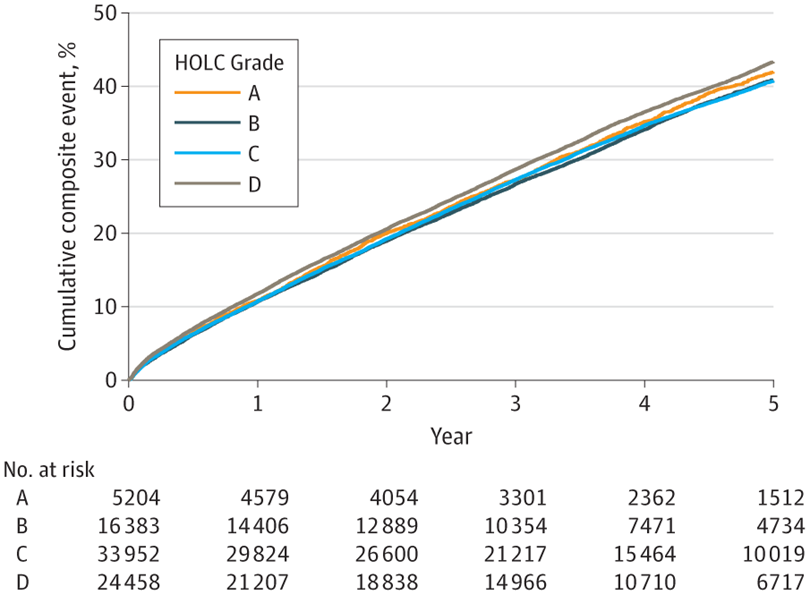

Click to Enlarge: Cumulative positive events for composite cardiovascular outcomes. HOLC indicates Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. Source: JAMA Network Open

Of 79,997 patients (mean age 74.46) 2.9% were female, 55.7% were white, 37.3% were Black, and 5.4% were Hispanic. A total of 7% of the individuals resided in HOLC grade A neighborhoods, 20% in B neighborhoods, 42% in C neighborhoods, and 31% in D neighborhoods. Compared with grade A neighborhoods, patients residing in HOLC grade D (redlined) neighborhoods were more likely to be Black or Hispanic with a higher prevalence of diabetes, heart failure and chronic kidney disease.

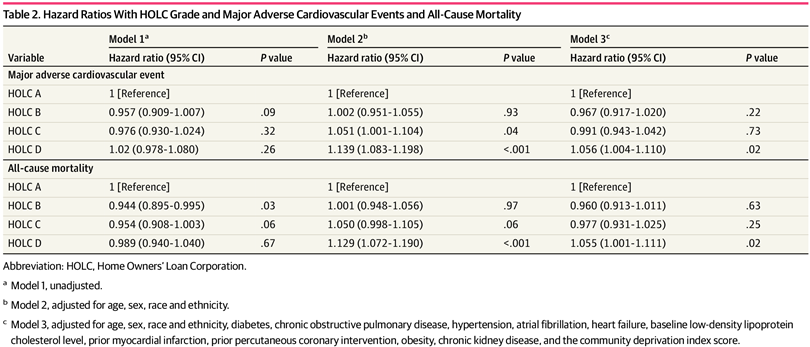

There were no associations between HOLC and major adverse cardiovascular events in unadjusted models, the study found. After adjustment for demographic factors, however, those residing in redlined neighborhoods had an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality compared to in grade A neighborhoods. Similarly, veterans residing in redlined neighborhoods had a higher risk of myocardial infarction but not stroke. Hazard ratios were smaller, but remained significant, after adjustment for risk factors and social vulnerability.

“If you compare the regions that are colored green—which are desirable—and colored red—which is undesirable—we see that the prevalence of minorities is higher in the undesirable regions,” said Salil Deo, MD, the study’s first author. Black individuals composed 25% of the population of the desirable regions, but 47% of the less desirable regions, the study found. Similarly, Hispanics composed 3.9 % of the green (desirable) areas but almost double that percentage (6.4) of the redline regions.

‘Not Much Has Changed’

Click to Enlarge: Hazard Ratios With HOLC Grade and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality Source: JAMA Network Open

“Our study demonstrates that, if you classify neighborhoods as good or bad based on their situation in 1930 and 1940, not much has really changed,” said Deo, an associate professor of surgery at the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) School of Medicine and a specialist in vascular surgery who treats patients at Louis Stokes VA Hospital in Cleveland. “That is actually the very important message that our study shows, because using information to classify neighborhoods which was available in the 1940s and linking back with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular outcomes in 2021 these redline neighborhoods still continue to have almost 13 to 14 percent higher relative risk of having adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction, stroke and death.”

While some smaller studies have looked at the lingering impact of redlining on health in individual cities, the new study is the first to look at it on a large national scale.

The researchers—who also included Yakov Elgudin, MD, PhD, director of lung transplantation at UH Cleveland Medical Center and associate professor of surgery at CRWU School of Medicine, and Sadeer Al-Kindi, MD, a researcher from Harrington Heart and Vascular Institute at University Hospitals and CWRU—chose cardiovascular disease, not only because it is their main area of research, but also because it is the leading cause of death and has been for many years, Deo said. Thus, insight from the study could have the potential to save many lives.

The study authors hope their research findings can be used to educate physicians about social determinants of health when meeting with and evaluating patients in their clinics, Deo said.

“When we meet with patients in our clinic, we really don’t think of where they come from—we think of their blood pressure,” he said. “I think it is important to evaluate these things, too, and get a more holistic picture of the patient and understanding of the patient to be able to provide them with the optimal medical therapy that they deserve.”

The team’s next step is to incorporate neighborhood data into risk models to guide physicians ascertaining risk and planning treatment. “A risk model is like a calculator where we put in the patients’ data—details like height, weight, BMI, diabetes and common lab values like blood sugar levels and cholesterol levels—and we get their five-year or 10-year predictive risk for having a heart attack,” Deo explained. “We use these models to start various therapies like statins and blood pressure control. But none of these models really incorporate the social determinants of health, and so we are currently working on developing and designing some of these commonly used models to include social determinants of health, and we are doing that using data from U.S. veterans.”

- Deo SV, Motairek I, Nasir K, Mentias A, Elgudin Y, Virani SS, Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi S. Association Between Historical Neighborhood Redlining and Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Veterans With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jul 3;6(7):e2322727. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.22727. PMID: 37432687; PMCID: PMC10336624.