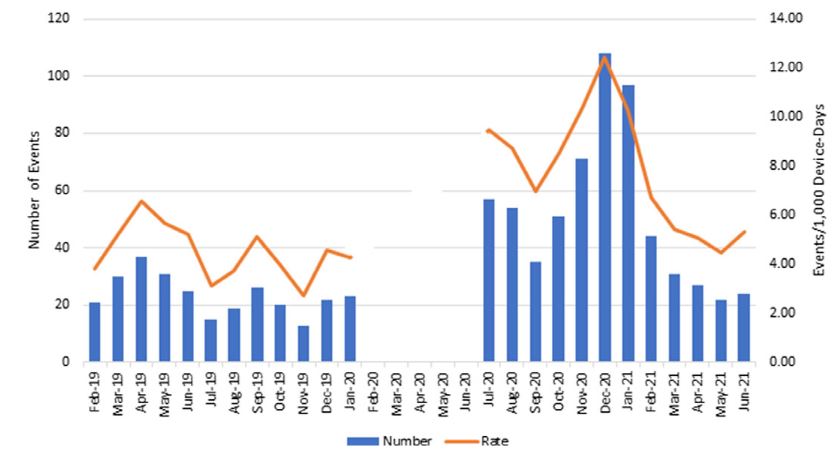

Click to Enlarge: Nationwide ventilator-associated-events (VAEs) and rates in acute care facilities 1 year before (baseline) and 1 year during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Data were not required to be reported from February through June 2020.) Source: Cambridge University Press

WASHINGTON, DC — The COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on hospital acquired infections in various types of VA acute care was a mixed bag, although, overall, many rates increased, according to a new study.

A study published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology sought to assess how SARS-CoV-2 affected HAIs reported by 128 acute care and 132 long-term care VA facilities.1

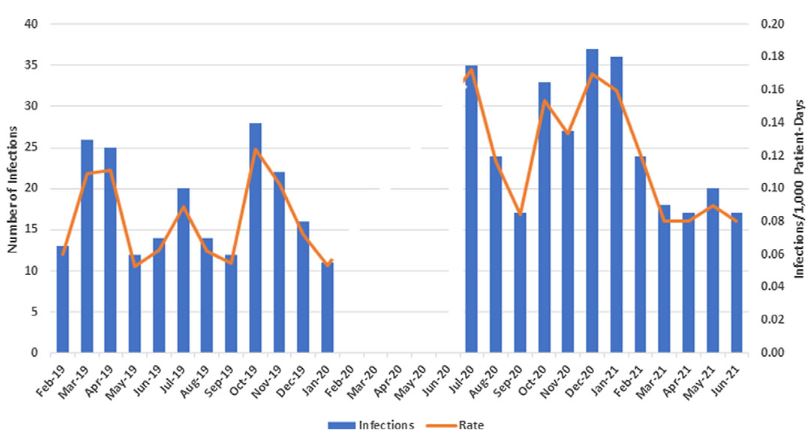

Researchers led by the VHA’s National Infectious Diseases Service in Washington and the Lexington, KY, VA Healthcare System quantified rates of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), ventilator-associated events (VAEs), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridioides difficile infections and rates reported from each facility monthly to a centralized database. Cases were compared before the pandemic (February 2019 through January 2020) to during the pandemic (July 2020 through June 2021).

“Nationwide VA COVID-19 admissions peaked in January 2021,” the authors wrote. “Significant increases in the rates of CLABSIs, VAEs, and MRSA all-site HAIs (but not MRSA CLABSIs) were observed during the pandemic period in acute care facilities. There was no significant change in CAUTI rates, and C. difficile rates significantly decreased. There were no significant increases in HAIs in long-term care facilities.”

Click to Enlarge: Nationwide methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) health-care-associated infections and ratesper 1,000 patient days in acute-care facilities 1 year before (baseline) and 1 year during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Data were not required to be reported from February through June 2020) Source: Cambridge University Press

Researchers suggested that evolving diagnosis testing might explain the decrease in CDI HAIs. “The minimal impact of COVID-19 in VA long-term facilities may reflect differences in patient numbers and acuity and early recognition of the impact the pandemic had on nursing home residents leading to increased vigilance and optimization of infection prevention and control practices in that setting,” they added. “These data support the need for building and sustaining conventional infection prevention and control strategies before and during a pandemic.”

The VA was in a good position because, over the past decade, the healthcare system has made strides in fighting healthcare-associated (sometimes called hospital-acquired) infections, such as C. diff, and MRSA.

Such advances have been evidenced in a number of recent studies, including a 2020 study in JAMA Network Open which surveyed VA hospitals concerning the use of infection-control practices and a 2021 study in the same journal which examined the association between contact precautions and transmission of MRSA in VA hospitals.

In the former, researchers at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, surveyed 320 infection preventionists at VA hospitals every four years between 2005 and 2017. They found that the use of 12 different infection-control practices increased in VA hospitals between over the 12-year period. Further, they found that, in all, since 2013, 92% to 100% of the VA hospitals analyzed indicated that they routinely used key infection-prevention protocols for C diff and central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) to reduce incidence.2

In the latter, researchers at the VA Salt Lake City Health Care System and University of Utah School of Medicine found the transmissibility of MRSA was reduced by approximately 50% among patients with contact precautions. They noted their results provide an explanation for decreasing acquisition rates in VA hospitals since the MSRA Prevention Initiative, a nationwide effort to reduce MSRA transmission, launched in October 2007. 3

“For many years the VA has really tried to give its hospitals resources for both infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship. Antimicrobial stewardship teams help optimize antimicrobial use in a hospital to improve patient outcomes,” said Payal Patel, MD, MPH, assistant professor of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan and medical director of Antimicrobial Stewardship at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Antimicrobial stewardship is a coordinated program that promotes the appropriate use of antimicrobials (including antibiotics), improves patient outcomes, reduces microbial resistance, and decreases the spread of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms, according to the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). “For many years, the VA has kind of been ahead of the game in both of those areas,” she said.

Stretched Thin

But as the pandemic began, and hospital staffs were stretched thin and resources were diverted to care for COVID-19 patients, Patel and her colleagues questioned whether such changes would lead to changes in testing or increased healthcare acquired infections.

Their concerns prompted a study, which found for at least one infection at one VA hospital the answer was a reassuring no.

The researchers conducted a single center, retrospective, observational study at the VA Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, between January 2019 and June 2020. They compared data on C diff tests from January 2019 through February 2020 to data from March 2020—the admission of the first patient with COVID-19 at the institution—through June 2020. 4

Between Jan. 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020, there were 6,525 total admissions and 34,533 bed-days. The number of admissions COVID-19 ranged from six to 27 patients each month. There were 900 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) tests obtained and 104 positive cases of CDI between January 2019 and June 2020. Percent positivity of CDI tests ranged from 6% to 22% and was not significantly different in the pre- vs. peak-pandemic periods.

In terms of testing, however, there were some noted differences. “There was a statistically significant decrease in EIA tests after March 1, 2020 (the COVID-19 peak in their region), compared to Jan. 1, 2019-March 1, 2020,” the investigators wrote in Anaerobe. “After March 1, 2020, the number of EIA tests obtained decreased by 10.2 each month (95% Confidence Interval [CI] -18.7 to -1.7; p=0.02).”

Patel cautioned the study’s findings were from a single center and might not be representative of the VA as a whole. “I think it is kind of hard, because the VA is a huge federal system, and you can look at it from a macroscopic view but also from a microscopic view,” she said. “Each hospital is also kind of different on its own and has different resources for infection control and stewardship programs as well.”

Findings of larger studies looking at different infections at hospitals outside the VA have shown that HAIs likely were affected during the pandemic. For example, a large national study analyzing laboratory-identified events reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network for 2019 and 2020 by acute-care hospitals found significant increases in the national standardized infection ratios for CLABSI, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), ventilator-associated events (VAEs) and MRSA bacteremia were observed in 2020. Changes in the standardized infection ratios varied by quarter and state. The largest increase was observed for CLABSI, and significant increases in VAE incidence and ventilator utilization were seen across all four quarters of 2020.5

“Our study is just one drop in a large swath of people looking at this,” said Patel. “But I don’t know if there has been a ton of VA work published on this yet. I am interested to see more and more from colleagues from the VA on what the impact of the pandemic was on healthcare-associated infections.”

For now, she said lessons learned from the pandemic have a message for the future. “I think there are some things that are unavoidable. When you are in the midst of a pandemic, you have to divert some of the resources that you are usually using to think about things like healthcare-associated infections,” she said. “But if this was going to happen again in our lifetimes, I think some of the data we have discovered during this time could potentially be helpful for planning—how do we work with infection control programs and stewardship programs to try to do the day to day, but also work on this other stuff. Maybe this starts with providing programs with more resources, more people.”

- Evans ME, Simbartl LA, Kralovic SM, Clifton M, et. al. Healthcare-Associated Infections in Veterans Affairs Acute and Long-Term Healthcare Facilities During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022 Apr 5:1-24. doi: 10.1017/ice.2022.93. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35379366.

- Vaughn VM, Saint S, Greene MT, Ratz D, Fowler KE, Patel PK, Krein SL. Trends in Health Care-Associated Infection Prevention Practices in US Veterans Affairs Hospitals From 2005 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920464. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20464. PMID: 32022877.

- Khader K, Thomas A, Stevens V, Visnovsky L, Nevers M, Toth D, Keegan LT, Jones M, Rubin M, Samore MH. Association Between Contact Precautions and Transmission of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Veterans Affairs Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Mar 1;4(3):e210971. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0971. PMID: 33720369; PMCID: PMC7961311.

- Hawes AM, Desai A, Patel PK. Did Clostridioides difficile testing and infection rates change during the COVID-19 pandemic? Anaerobe. 2021 Aug;70:102384. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2021.102384. Epub 2021 May 23. PMID: 34029702; PMCID: PMC8141342.

- Weiner-Lastinger LM, Pattabiraman V, Konnor RY, Patel PR, Wong E, Xu SY, Smith B, Edwards JR, Dudeck MA. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections in 2020: A summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022 Jan;43(1):12-25. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.362. Epub 2021 Sep 3. Erratum in: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022 Jan;43(1):137. PMID: 34473013.