Ketamine, Esketamine Suggested for Unresponsive Patients

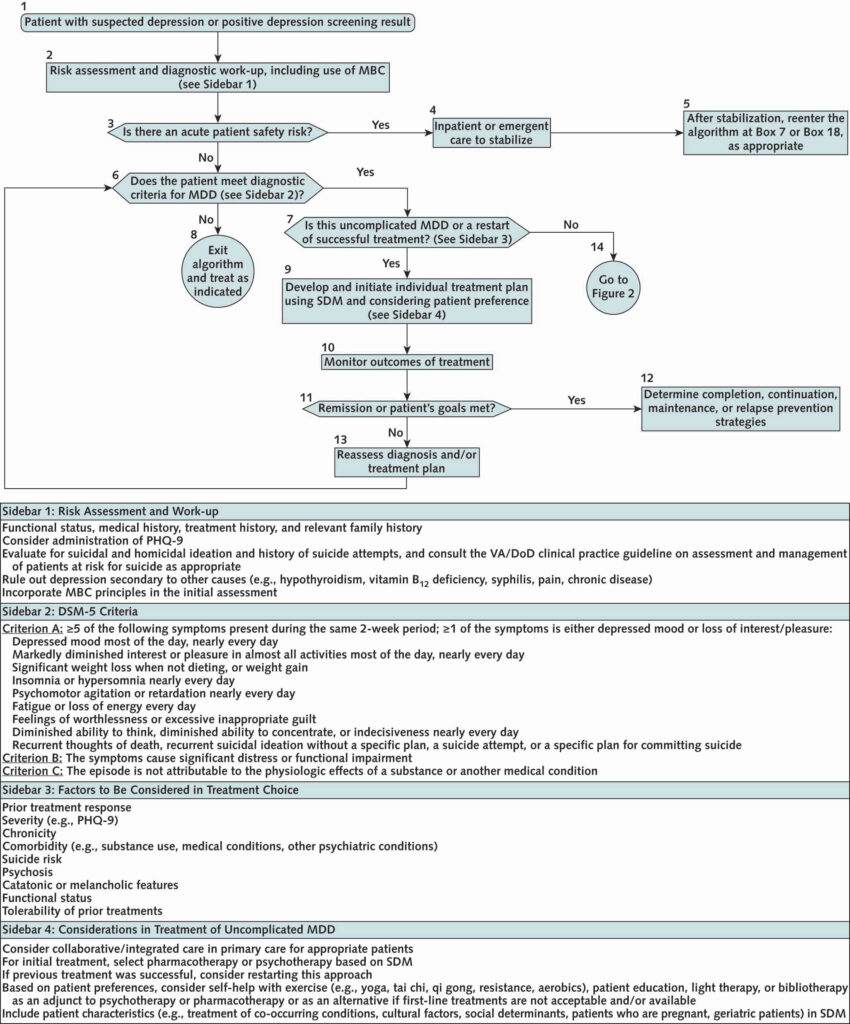

Click to Enlarge: Initial assessment and treatment.

DoD = U.S. Department of Defense; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; MBC = measurement-based care; MDD = major depressive disorder; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SDM = shared decision-making; VA = U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

SAN FRANCISCO ― Expansion of interventional psychiatry and updated algorithms to help guide physicians in making choices about therapies for depression are among important updates included in the newly revised 2022 VA-DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Major Depressive Disorder.

The guideline, created to guide care provided by the DoD and VA staff as well as care obtained by the DoD and VA from community partners, is systematically updated every five to six years to reflect the most current research on depression treatment, said John McQuaid, PhD, associate chief of staff for health equity at San Francisco VA Health Care System and a leader of the work group for the guideline revision.

For the update, senior leaders within the VA and DoD assembled a team that included clinical stakeholders and conformed to the National Academy of Medicine’s tenets for trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. The guideline panel developed key questions, systematically searched and evaluated the literature, created two one-page algorithms, and distilled 36 recommendations for care using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system. Select recommendations that were identified by the authors to represent key changes from the prior clinical practice guideline, published in 2016, were presented in a synopsis published in the October Annals of Internal Medicine.1

What’s New About the 2022 Guideline

Changes from the previous guideline include:

- A recommendation to suggest ketamine or esketamine as a treatment option in patients who have not responded to several pharmacologic trials. “The 2016 guideline recommended against the use of ketamine to treat major depressive disorder outside of research settings while noting there was a gap in knowledge related to its use,” the authors wrote. Esketamine was not commercially available when the previous guideline was written; therefore, it was not included. Current evidence suggests that both ketamine infusion and intranasal esketamine improve depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

- An amended recommendation for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). A review of the current literature on rTMS did not change the 2016 recommendation that suggested its use among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who have shown partial or no response to two or more adequate pharmacologic treatment trials. “However, there is a new version called theta-burst stimulation, and we did not find sufficient evidence to recommend this version of RTMS,” McQuaid said.

- A recommendation for bright light therapy. Bright-light therapy was developed as an intervention for people with seasonal affective disorder, and there has been evidence it is an effective intervention for that population, said McQuaid. Recent research shows its benefits are not limited to people with a seasonal pattern to their depression. “Now we are able to recommend it regardless of whether the person has a seasonal pattern for their depression or not,” he said.

- Increased psychotherapy options. In the previous guideline, six forms of psychotherapy―acceptance and commitment therapy, behavioral therapy/behavioral activation, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and problem-solving therapy―were recommended for initial treatment of depression. The updated guideline includes short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) as an evidence-based psychotherapy for depression, said McQuaid. “That is important, because a lot of people provide that short treatment and the data on it had not been clear.”

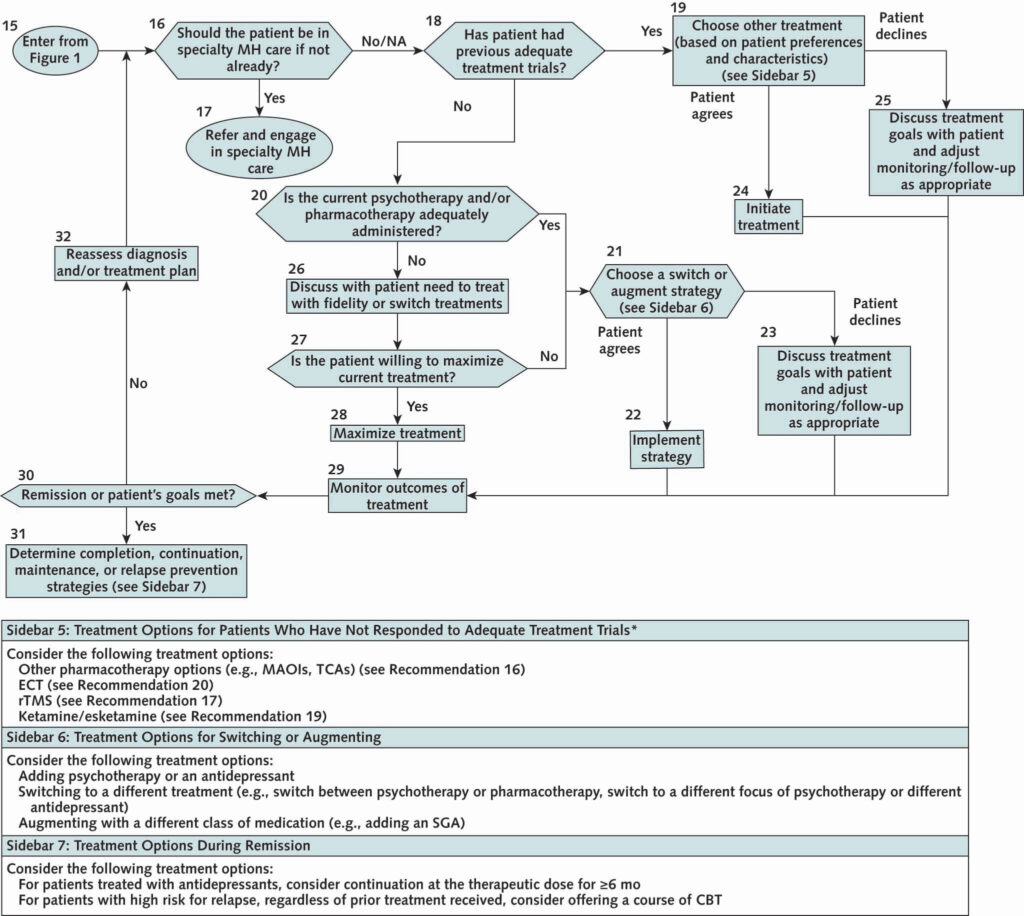

- A restructured treatment algorithm. The revised algorithm has two components: The first provides guidance for initial screening, evaluation and treatment of uncomplicated depression or reinitiation of treatment for someone who previously was successfully treated. The second provides guidance for treatment of patients who either are not initially responsive to care or have complicating factors that indicate a higher level of care. “It takes you to a next level of decision-making, so that we hope will make it easier for clinicians and providers to have a guide into how to make decisions around treatment,” he said.

- A review of telehealth. Due to the increased reliance on telemedicine resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the work group looked to see if there was any evidence for or against about efficacy of telehealth versus non-telehealth, said McQuaid. “At this point, we don’t have any evidence that telehealth is any better or worse than in-person treatment,” he said. “We couldn’t say one was better than the other, which in the big picture, is probably a good thing.”

Interventions Considered but Not Recommended at This Time

Click to Enlarge: Advanced care management. CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy; MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MH = mental health; NA = not applicable; rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; SGA = second-generation antipsychotic; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant.

* Patients who have shown partial or no response to initial pharmacologic monotherapy (maximized) after a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks.

Not all reviews of current literature led to changes in previous recommendations. Interventions considered but not recommended for the 2022 guideline included hallucinogens and pharmacogenomic testing.

- Hallucinogens. The literature search for research on hallucinogens for the treatment of depression produced one small study of psilocybin. Although those who completed the study had significantly improved depressive symptoms at weeks 5 and 8, concerns about psilocybin―including potential for dependence and the risk for psychotic events and harmful behavior in patients who do not receive appropriate guidance throughout the treatment process―and limited evidence related to psilocybin’s safety and efficacy, led the work group to recommend against its use. The work group also recommends against the use of MDMA, cannabis or other unapproved pharmacologic agents in settings outside clinical trials. Trials in veterans are currently under way and may provide more clarity on the utility of psilocybin in the future, they wrote.

Pharmacogenomic testing. The work group reviewed evidence on the use of pharmacogenomic testing as a guide for selecting antidepressants and determined there was not sufficient evidence to make a recommendation either for against its use. “Although there is extensive interest in developing approaches to better match patients to treatments, only one systematic

review that included four [randomized controlled trials] and two open-label trials was available, along with limited additional RCTs,” the authors wrote. “Overall, the findings were mixed in terms of outcomes, and the quality of evidence was very low due to small sample sizes and concerns about potential bias because the studies were commercially funded.”

The Importance of Guidelines

Because research has shown that depression affects active military personnel and veterans at a significantly higher rate than that of the civilian population, treatment guidelines geared to that population are exceedingly important. “The fact that these guidelines are updated consistently―the VA ad DoD have a structure in place to assure updates―really helps to keep us at the forefront of what the current literature tells us,” McQuaid said.

In addition to the full guideline, the VA and DoD also produce a selection of materials to help providers, patients and families guide their decision-making, McQuaid said. For more information, he suggested the following link:: Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (2022)

- McQuaid JR, Buelt A, Capaldi V, Fuller M, Issa F, Lang AE, Hoge C, Oslin DW, Sall J, Wiechers IR, Williams S. The Management of Major Depressive Disorder: Synopsis of the 2022 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2022 Oct;175(10):1440-1451. doi: 10.7326/M22-1603. Epub 2022 Sep 20. PMID: 36122380.