MILWAUKEE — In less than two decades, the advent of targeted therapies transformed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) from a death sentence with a five-year survival rate of just 22% to a chronic condition with five-year survival exceeding 90%. To achieve that extraordinary increase in survival, most patients have committed to taking medication every day for the rest of their lives to keep the disease in remission.

Now, researchers have their sights set on enabling many patients with CML to live long and healthy lives free of treatment burdens, essentially to move from medicated remission to cure. The challenge lies in properly preparing patients and identifying those most likely to remain in remission.

CML is an unusual malignancy. It develops as a result of a single mutation, a genetic translocation that allows a piece of chromosome 9, the Abelson Gene (ABL1), to fuse to the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene on chromosome 22, to create the “Philadelphia chromosome” indicative of the disease. BCR-ABL1 is an oncogene that produces the BCR-ABL1 protein. The protein, in turn, promotes tyrosine kinase activity that drives proliferation and inhibits death of malignant cells in the bone marrow.

Because CML has a single, known cause, the method of treatment is clear, and remarkably effective. Four tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are FDA approved for first-line treatment of the disease: imatinib, dasatinib, bosutinib and nilotinib. A fifth, ponatinib, is approved for patients who have shown resistance to two other TKIs and have a specific mutation.

All five can induce deep, durable molecular response in patients with chronic phase CML, the stage at which the great majority of patients are diagnosed. Most patients treated with TKIs during the chronic phase and maintained on the drugs can now expect to live a nearly normal life span.

Staying on TKIs comes with downsides, however. The drugs must be taken daily, can be expensive and often have side effects including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, bone pain, fatigue, and skin rashes. TKIs may also worsen or cause cardiovascular disease.

Treatment-free Remission

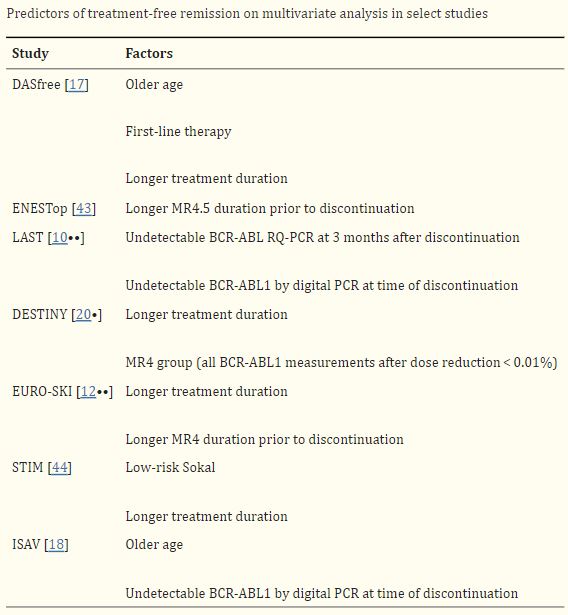

Click to Enlarge: Droplet digital PCR is a highly sensitive method for detecting the BCR-ABL1 transcript [21]. Patients with undetectable BCR-ABL1 by ddPCR at time of discontinuation are more likely to achieve a successful TFR than those whose BCR-ABL1 is undetectable by RQ-PCR but detected by ddPCR [10••, 18]. In the LAST study, the rate of molecular recurrence was higher for patients with detectable BCR-ABL1 by RQ-PCR (50%) or ddPCR only (64%) vs. patients with undetectable BCR-ABL1 by both RQ-PCR and ddpCR (10.3%) [10••]. In addition, two large studies have demonstrated that the BCR-ABL1 level at 3-month post-TFR is highly predictive of maintaining TFR [10••, 22]. In the ENESTfreedom study, the rate of successful TFR at 96 weeks was 82.6%, vs. 0% for patients with BCR-ABL1 < 0.0032% vs. those with BCR-ABL1 0.01 to 0.1%. Transcript type has also been shown to affect rates of successful TFR. Patients with e14a2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type are more likely to achieve MR4.5 and more likely to have a successful TFR after stopping TKIs [23–25]. In a retrospective study from the Adelaide group, 70% of patients with e14a2 BCR-ABL1 transcript achieved MR4.5 by 6 years compared to 52% with e13a2. Of the patients who were eligible to attempt TFR, patients with e14a2 were more likely to remain in TFR compared to those with e13a2 (65% vs. 34%) [23]. Early BCR-ABL1 kinetics predict successful TFR. In one study, patients with BCR-ABL1 halving time < 9.35 days were more likely to achieve a sustained TFR after discontinuation (80% vs. 4%) [26]. Source: Nature Public Health Emergency Collection

Over the last 15 years, several studies have demonstrated that some patients can safely discontinue treatment with TKIs. How and why the chromosome does not resume production of the BCR-ABL1 protein remains a mystery.

“We don’t know the answer,” said Ehab Atallah, MD, professor of hematology and oncology at the Medical College of Wisconsin and a hematologist with the Zablocki VAMC in Milwaukee.

“There are three groups of patients after stopping TKI therapy,” he told U.S. Medicine. “The first group has no detectable BCR-ABL and no disease relapse. The second group has detectable BCR-ABL and no disease relapse, so despite the presence of the mutation, they do not develop clinical CML. Some theories are that the cells that have the BCR-ABL are not cells capable of replication and causing the disease.” he added, noting that the third group has detectable BCR-ABL, which leads to relapse.

While researchers do not know why patients fall into one category rather than another after stopping TKIs, they do “know the longer they are on the drug and in deep remission, the more likely they will stay in remission,” Atallah added.

Start with Deep Remission

In a review Atallah authored with Kendra Sweet, MD, of the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fl, they note that attempting treatment-free remission (TFR) is recommended for “patients who have been on TKI for at least three years, have a sustained deep molecular response for at least two years, are in chronic phase CML, and have to evidence of an ABL kinase domain mutation.” While three years of treatment is the minimum, research shows that a longer duration of TKI therapy improves the likelihood of TFR.

What counts as “deep molecular response” has changed over time. Early studies of TFR selected patients in molecular response 5 (MR5) but more recent studies have shown equal success in attempting TFR with patients in MR4.5 and even MR4. More surprisingly, 36% of patients in major molecular remission rather than deep remission achieved TPR in a recent study. In good news for many veterans with CML, older age is associated with greater success in achieving TFR. Undetectable BCR-ALK increased success with TFR.

Among the 40% to 60% of patients who meet the durable, deep response criteria, “the rate of successful TFR is approximately 50% regardless of type of TKI,” the authors noted. Second-generation TKIs boost the likelihood of achieving MR4 or greater and can cut the time needed to do so, but they cost substantially more than imatinib.

Patients who lose major molecular response after discontinuing TKIs should resume treatment, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and other groups. Molecular recurrence is most likely in the first six months following discontinuation (35%), dropping to 8% in months 7 to 12 and 3% for months 13 to 18 and months 19 to 24. Consequently, monitoring should occur monthly for the first six months, every two months from month 7 to 12, and then to quarterly checks. Late recurrence is uncommon, but patients should be continued to be monitored indefinitely.

Some patients have successfully achieved TFR despite a molecular recurrence after a first attempt. The patients regained deep response before the second attempt and, in one study, 50% maintained TFR through a median follow-up of 8.6 years.

Looking ahead, Atallah said he sees achieving TFR as a goal for more patients, but notes the “TKIs alone are not the answer to achieving a cure.” Currently, about 20% of patients with CML will achieve TFR, but a number of studies evaluating whether other drugs can enhance those rates are in process. One is looking to see whether ruxolitinib or pembrolizumab can increase the number of patients who attain deep response, while another is evaluating the addition of ruxolitinib or asciminib to TKI therapy to help sustain a second TFR.

- Atallah E, Sweet K. Treatment-Free Remission: the New Goal in CML Therapy. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2021 Oct;16(5):433-439. doi: 10.1007/s11899-021-00653-1. Epub 2021 Oct 7.