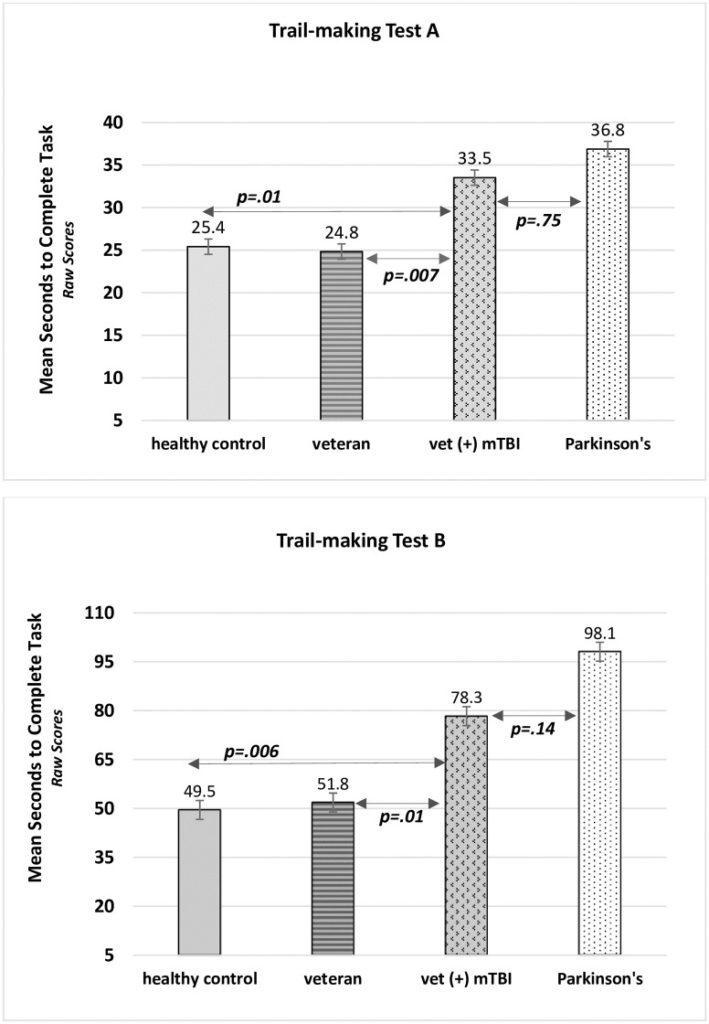

Click to Enlarge: Trail-making A and B reveal group differences and similarities in cognitive flexibility.

FORT WORTH, TX — Between 2000 and 2018, approximately 430,000 active-duty servicemembers suffered head injuries. Although more than 82% of those were classified as mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI), new research suggests that even mild, nonpenetrating injures might lead to serious consequences down the line.

Mounting evidence suggests that veterans with mTBIs showed subtle signs of premature cognitive function decline that could portend the eventual onset of Parkinson’s disease or other neurogenerative diseases.

Traditionally mTBI’s have been thought to be self-limited, resolving in three to six months, explained Vicki Nejtek, PhD, associate professor in the Institute for Healthy Aging, and Pharmacology and Neuroscience University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth, TX.

When evaluating the effects of past concussions, neurologists have typically used the mini-mental state exam, which includes tests of orientation, attention, memory, language and visual-spatial skills. But Nejtek, the lead author of a study in PLoS One, theorized that the widely used test was not sensitive enough for evaluating the effects of mild injuries. “It is not sensitive enough to determine neurodegeneration becomes a really serious condition, so you are missing a lot of people with the assessment,” she said.1

Nejtek suggested that the damage from mTBIs affects only very specific regions of the brain—not the global damage the mini-medical state exam was designed to evaluate—and that a better understanding of those regions and the effects on injuries on them might help identify veterans were at risk of the long-term effects of mTBIs and ways to prevent their progression.

To test that theory, she and her colleagues studied 114 subjects—including veterans with and without mTBIs, healthy controls and people with early stage Parkinson’s disease. All mTBIs were nonpenetrating injuries occurring within the past seven years that resulted from military-related blasts/explosions, motorized accidents, physical assaults or falls. All subjects were administered the Trail-Making Test, a pen and pencil tool/text evaluation tool used to assess cognition—the ability to think, reason and remember. Scoring of the tests—which are administered in two parts, A and B—is based on the length of time it takes to complete the test, with the goal being to complete the tests as accurately and quickly as possible.

Veterans with mTBIs took significantly longer to take the test compared to veterans without such injuries and healthy controls, to a degree that was not expected. “When I found out that these young veterans, an average age of 36 or so, that they were performing this task as if they were 70 years old or someone with early Parkinson’s it was surprising,” Nejtek said.

She cautioned that such deficits—even short term—can have serious consequences, particularly for military personnel who “have to make strategic decisions on a moment’s notice.” She adds that recognizing the damaging effects of such injuries early on may offer the opportunity for the therapies—many that don’t involve medication—to slow or prevent their progression.

Specific Cognitive Domains

Najtek said the new study is the first to show subtle premature cognitive decline occurring in very specific cognitive domains in veterans with mTBI that would typically could be overlooked in a clinic setting. She noted that earlier studies by herself and colleague Michael F. Salvatore, PhD, also at the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth have shown the cognitive symptoms of Parkinson’s can manifest years before motor onset—the premotor phase.

“We wanted to say if this is happening with Parkinson’s and people with mild TBI aren’t even getting screened may be this is how Parkinson’s is allowed to develop because there were signs but nobody picked up on them,” she said.

Background information in the articles pointed out that, based on epidemiologist reports, veterans with mTBI have a 56% increased risk of developing idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) within 12-years post-injury. “This finding is critically important, as over 82% of the ~430,000 head injuries suffered by active-duty servicemen and women from 2000-2018 were classified as mTBI,” the authors pointed out.

Furthermore, the study noted that Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn veterans were documented as having the greatest number of nonpenetrating mTBI compared to military personnel involved in any other previous conflict.

Researchers suggested that “examining any similarities in cognitive abilities between young mTBI and older early-stage PD could provide much-needed evidence of a cognitive phenotype characterizing mTBI-related links to or risks for PD when used in conjunction with other prodromal PD characteristics (i.e., REM sleep disorder, hyposmia, etc.)”

Natjek’s team is currently assaying blood samples from the participants to look for serum-based biomarkers. “The next publication I am working on is to use the information from this study to analyze the biomarkers with the cognitive markers of premature cognitive decline to see if there is any way we can identify what is happening from the physiology,” she said.

- Nejtek VA, James RN, Salvatoe MF, Alphonso HM, Boehm GW. Premature cognitive decline in specific domains found in young veterans with mTBI coincide with elder normative scores and advanced-age subjects with early-stage Parkinson’s disease. PLOS One. Published November 17, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258851