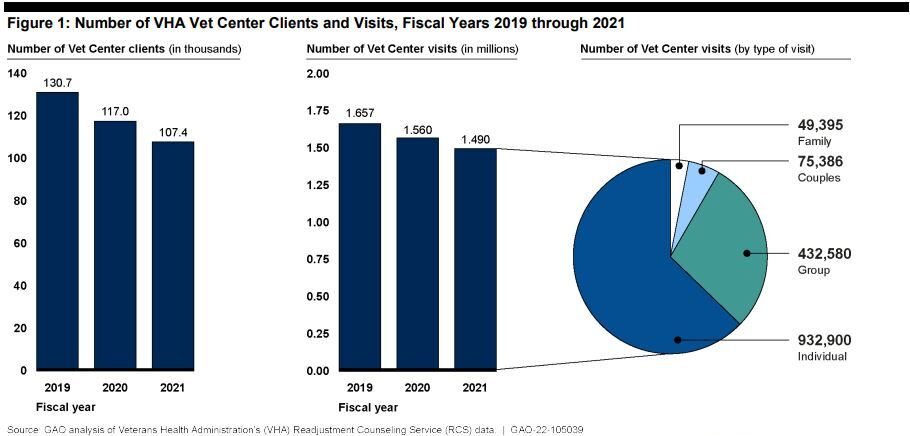

Click to Enlarge: Note: Fiscal year 2019 is the most recent fiscal year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and RCS officials attributed the declines in Vet Center clients and visits from fiscal years 2019 through 2021 to the pandemic.

WASHINGTON, DC — VA’s Vet Centers are repeatedly falling short when it comes to properly assessing and documenting veterans’ suicide risk, according to department watchdogs. Poor training, understaffed facilities and a lack of strong oversight all may contribute to scenarios where in-crisis veterans do not receive the full range of help that they need.

VA’s Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Vet Centers were originally created to help serve Vietnam veterans who were reluctant to seek care at VHA facilities. Staffed heavily with veterans, the centers offer nonmedical readjustment services in what is intended to be a nonstigmatizing atmosphere. Recent legislation expanded Vet Center eligibility to servicemembers pursuing certain educational benefits, as well as to family of servicemembers and veterans who have died by suicide.

Beginning in 2020, the VA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) initiated the Vet Center Inspection Program, a series of cyclical inspections meant to ensure that counseling in those facilities is provided in accordance with VHA policy. The OIG published nine reports between September 2021 and May 2023 covering every Vet Center district and have unearthed concerning systemic issues.

“We repeatedly find evidence of noncompliance with many required processes. Most notably those for assessing and documenting a veteran’s suicide risk,” OIG Principal Assistant Deputy Secretary Julie Kroviak, MD, told the Senate VA Committee at a hearing last month. “Our teams are finding repeated failures of staff oversight of training and supervision. These deficiencies can have severe consequences.”

While identifying the deficiencies was the first step, it took multiple rounds of inspections to pinpoint root causes. A main one is a lack of clear policies supporting frontline staff, according to the findings.

“We repeatedly found incidences where Vet Centers staff report confusion, conflicting policy language or unnecessary cumbersome processes to conduct basic tasks in support of their clients,” Kroviak said. “Tools such as a SharePoint site that identifies clients as high risk for suicide are neither effectively or consistently utilized, as many staff members report they were never informed of their purpose. [They are] perplexed at the inefficiencies in the multiple steps needed to enter basic information. They are also repeatedly misinformed by the site’s inaccurate information.”

Workload and staffing challenges also are a concern at most of the Vet Centers.

“We frequently met with leaders in acting positions or leaders assuming multiple roles to compensate for vacancies, which are in part due to the inability to compete with the clinical salaries offered by VA medical centers,” Kroviak said. “This leads to client workloads some counselors have described as unsustainable.”

A culture of safety must begin at the leadership level, she emphasized, and there have been failures there, as well, most notably at a Vet Center in South Bend, IN. In a January 2023 report, the OIG found that the Vet Center’s director had been informally urging staff to rate veterans lower for suicide risk than they actually were to avoid the attention of RCS leadership. The director also failed to evaluate staff’s completion of safety plans and clinician coordination, and failed to train staff on assessing and managing client’s risk of suicide.

That director has since been removed.

“Considering Vet Centers can be the first door a veteran in crisis opens to engage in care, there is no room for careless and incompetent leadership,” Kroviak declared.

Recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports found similar deficiencies, as well as a general inability of Vet Centers to assess their own effectiveness or to determine what barriers existed for veterans seeking their services.

RCS Chief Michael Fisher noted that the problem in evaluating suicide risk might be an artifact of poor documentation, rather than poor care, and that these veterans are being connected to VHA services but that those connections are not being recorded in the record.

“What my concern is that I don’t know if we are documenting those results correctly,” Fischer told legislators.

Kroviak concurred that the ability to document and timestamp processes in Vet Center’s online systems is limited, but that it should not be an excuse for not tracking the care of veterans.

“There are also issues with making sure staff are even properly trained to conduct these screenings and assessments,” she said. “So it’s a training and oversight problem, as well.”

Despite these findings, legislators were complimentary about the Vet Center program, noting that it was especially useful in rural areas and in bringing in veterans who are intimidated about seeking care at a VA clinical facility.

“It’s much less structured, much more welcoming,” said Committee Chair Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT). “From my perspective, when I’ve visited, the stress level is zero.”