SEATTLE — The blood pressure medication prazosin might dramatically reduce the occurrence of headaches following mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), according to a new study by researchers at VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle.

The study, published in Headache, the Journal of Head and Face Pain, was conducted on 48 veterans and active-duty servicemembers with headaches related to mTBI.1

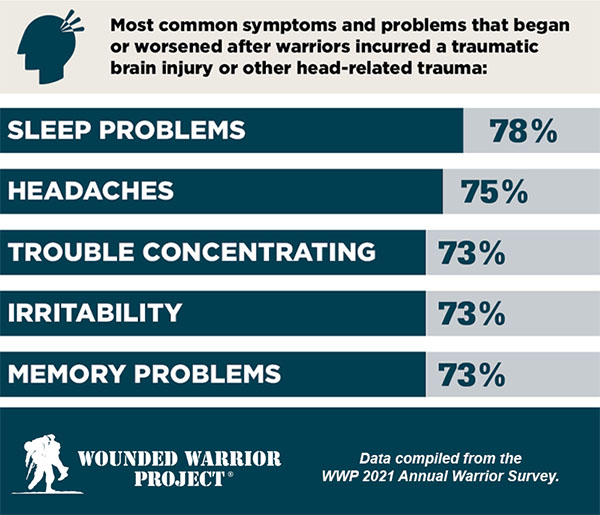

Often referred to as the “signature injury” of the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, such injuries have commonly been the result of blast explosions from improvised explosive devices, said Cynthia Mayer, DO, the study’s first author. Over the past two decades, more than 460,000 servicemembers have sustained a TBI, most of which were mild. Headaches are common following a mild TBI, and they often become chronic and cause substantial disability and distress.

Mayer and her colleagues at the VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (NW MIRECC)—which promotes the implementation of effective treatments for military post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and its complex comorbidities—designed the study based on International Headache Society consensus guidelines for randomized controlled trials for chronic migraine.

“We felt that probably post-traumatic headaches were going to be similar to chronic migraines. The benefit of using consensus guidelines such as that is that studies of different medications can be compared,” she said, adding that the group also made modifications for their study.1

“The consensus guidelines were really strict about which medications could be included or whether people should be excluded if they already failed three forms of headache medication, the reason being those people are considered to be refractory to any kind of treatment,” she said. Recognizing that soldiers are likely to have taken pain medications for other problems—for example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories for musculoskeletal pain—the researchers removed that exclusion. “The other thing was that the consensus guidelines recommended against including people with overuse headaches,” she said. “We changed that because otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to recruit anybody. We had to make adjustments based on our population.”

Following a pre-treatment baseline phase, participants with at least eight qualifying headache days per 4 weeks were randomized 2:1 to prazosin or placebo, so a person had double the chance of being on prazosin vs. placebo. “The reason we did that was to help with recruitment,” said Mayer. “We wanted to increase the odds of them being on an active drug, so we adjusted for that in our randomization scheme and in the analysis.”

After a 5-week titration to a maximum possible dose of 5 mg (morning) and 20 mg (evening), participants were maintained on the achieved dose for 12 weeks. Outcome measures were evaluated in 4-week blocks during the maintenance dose phase. The primary outcome measure was a change in the 4-week frequency of qualifying headache days. Secondary outcome measures were percent of participants achieving at least a 50% reduction in qualifying headache days and change in Headache Impact Test-6 scores, a self-report measure based on the answers to six questions regarding different aspects that might be affected by having a headache.

Headache Frequency

The most important finding, Mayer said, was the significant difference in the frequency of headache days between the people who took prazosin vs. placebo. By the end of the 12-week period, participants taking prazosin had headaches for an average of six days a month, while those receiving a placebo reported headaches an average of 12 days a month. The other key finding was in the percentage of participants who had a least a 50% reduction in their headaches—about 70% in the prazosin group after the 12th week of the study, compared to 29% in the placebo group. Self-reported disability related to headache was also significantly improved in the group on prazosin vs. placebo, Mayer said.

“We were surprised at how high the response rate was because, when we compared it with other studies that had been done for chronic migraine, it outperformed the other medications,” she said. “Of course, those were done in a larger sample size, but we were surprised at the magnitude of the response.”

With findings from the first 48 participants published, the researchers are now working on analyzing data from 48 additional participants. They expect to publish a follow-up paper later this year, Mayer said.

Prazosin, which was approved by the FDA in 1976 to treat hypertension, has been widely used off-label in the VHA to treat conditions such as nightmares and sleep disturbance associated with PTSD. Mayer said it is not well understood how the drug, an alpha-1 adrenoreceptor antagonist that reduces noradrenergic signaling, works to improve headaches, but the new study suggests it may work double-duty for people with PTSD.

“So many patients have PTSD. Prazosin is a medicine that could be used to treat a couple of things at the same time, so you can get that kind of benefit to minimize polypharmacy as much as possible,” she said.

“The thing about headache medicine is there is no one thing that helps everybody,” said Mayer. “That is why there are so many different headache medicines out there. We are not trying to say prazosin Will work for everyone, but it’s another option for people to use.”

In the published study, not all TBIs were related to blast injury, Mayer added. “We had one person from Vietnam who had an impact injury. One guy was hit in the head by a baseball. Traumatic brain injury is shockingly common.”

For most people who have had a mild traumatic brain injury, headaches resolve within six months. “But for some people, they don’t go away,” Mayer said. “So that is who we are trying to address with the study.”

- Mayer CL, Savage PJ, Engle CK, Groh SS, et. al. Randomized controlled pilot trial of prazosin for prophylaxis of posttraumatic headaches in active-duty service members and veterans. Headache. 2023 Jun;63(6):751-762. doi: 10.1111/head.14529. Epub 2023 Jun 14. PMID: 37313689.