Study Looked at Effect in Special-Ops Military Vets

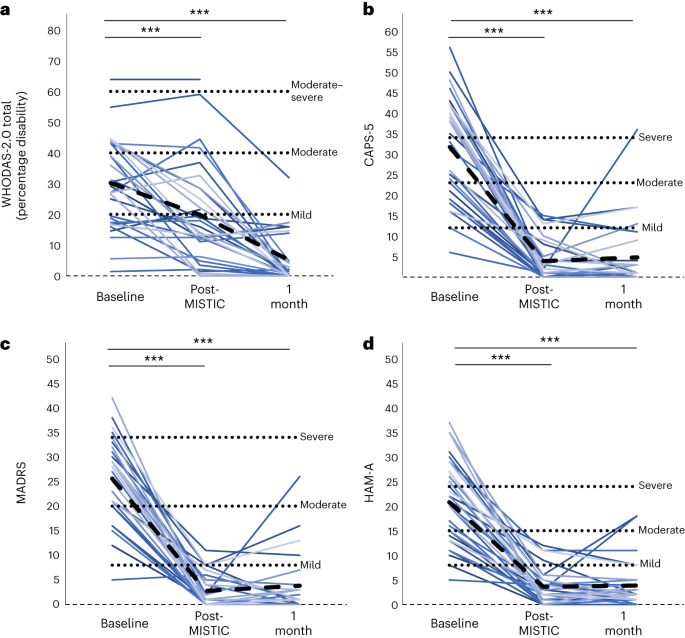

Click to Enlarge: a–d, Baseline and follow-up results in WHODAS-2.0 total (a), CAPS-5 (b), MADRS (c) and HAM-A (d). Individual colored lines represent individual participants. The dashed black line represents the mean. LME models were used for each comparison with FDR correction applied for determination of significance. ***PFDR < 0.001. Source: Nature Medicine

STANFORD, CA — The signature injury of U.S. veterans from recent military conflicts, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of injury-related disability. Often a consequence of blast exposure, TBIs can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders, with a resulting increase in suicide risk. TBIs also can cause changes in memory and attention that can substantially impact quality of life.

Because efficacy of treatments for these problems is limited, many veterans desperate for relief have been seeking underexplored therapies that are not available in the United States. Now a study out of Stanford University shows one of these underexplored therapies—ibogaine, a plant-based psychoactive drug that has been studied primarily as a treatment for substance-use disorders—is both safe and effective for TBI’s chronic complications.1

Derived from the root bark of the Tabernanthe iboga shrub and similar plants, ibogaine has a traditional use in African religious, spiritual and healing rituals. When administered therapeutically, it induces dreamlike states of consciousness, facilitating self-reflection and evaluation, said Nolan Williams, MD, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University Medical Center. It also affects multiple neurotransmitters at the same time.

Importantly, ibogaine is classified by the Controlled Substances Act as a Schedule I substance, defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Thus, legal restrictions have limited research with the drug in the U.S.

After learning of several veterans who had gone to a clinic in Mexico and were reporting anecdotally that they were experiencing significant improvements in their lives after taking ibogaine for their TBI-related conditions, Williams and his colleagues decided to scientifically evaluate the role of ibogaine for that purpose.

The study team collaborated with VETS Inc., a foundation dedicated to supporting psychedelic-assisted therapies for veterans. With assistance from VETS, 30 Special Operations Forces veterans (SOVs) who had a background of TBI and repeated blast exposures independently arranged for ibogaine treatment at a clinic in Mexico.

Prior to the intervention, the researchers assessed the participants’ PTSD, anxiety, depression and overall functioning levels using self-reported surveys and evaluations administered by clinicians. Subsequently, the participants traveled to a clinic in Mexico operated by Ambio Life Sciences, where, under medical supervision, they were administered oral ibogaine along with magnesium to mitigate potential heart-related complications associated with ibogaine. Following the treatment, the veterans came back to Stanford Medicine for follow-up assessments.

Reduction in Symptoms

Before ibogaine treatment, all participants had an average rating of 30.2 on the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale 2.0 (WHODAS), Williams told U.S. Medicine. “One month after treatment, that rating improved to 5.1, indicating no disability. One month after treatment, participants experienced average reductions of 88% in PTSD symptoms, 87% in depression symptoms and 81% in anxiety symptoms relative to pre-ibogaine treatment. Cognitive testing indicated improvements in concentration, information processing, memory and impulsivity in participants.”

He continued, “There were no serious side effects of ibogaine and no instances of the heart problems that have occasionally been linked to ibogaine. During the treatment, the veterans reported typical symptoms, including headaches and nausea.”

Williams and his colleagues stated that the study, published in Nature Medicine, is possibly the first to report evidence for a single treatment with a drug that can improve chronic disability related to repeated TBI from combat/blast exposures. Moreover, there is no currently available FDA-approved treatment for chronic sequelae of combat-related TB, they wrote.

While the study provides initial evidence to suggest that ibogaine could be a powerful therapeutic for the transdiagnostic psychiatric symptoms that can emerge after TBI and repeated exposure to blasts and combat, including suicidality, the authors stated replication of their findings is needed, particularly in non-mild TBI cases.

Considering that the average time since discharge from the military in our sample was nearly eight years, they stated their findings further suggest that treatment with ibogaine might be effective even when administered years after the injuries.

The researchers are planning further analysis of additional data collected on the veterans but not included in this current study, including brain scans that may help to reveal how ibogaine led to improvements in cognition, Williams said, adding. “We also hope to launch future studies to further understand how ibogaine may be used to treat TBI.”

Williams advised that ibogaine’s drastic effects on TBI also suggest that it holds broader therapeutic potential for other neuropsychiatric conditions. “In addition to treating TBI, I think this may emerge as a broader neuro-rehab drug,” he said. “I think it targets a whole host of different brain areas and can help us better understand how to treat other forms of PTSD, anxiety and depression that aren’t necessarily linked to TBI.”

The primary goal is to try to use the data to figure out how to do a U.S.-based trial, alongside the Food and Drug Administration, said Williams, noting there is likely to be interest in this treatment. “For example, there is a new bill that was just signed in to the law, the National Defense Authorization Act. Within it, there is $15 million earmarked to fund clinical trials researching ibogaine and other psychedelics as a treatment for traumatic brain injuries experienced by active duty members of the U.S. military.”

- Cherian, KN, Keynan, JN., Anker, L, Faerman, A, et al. (2024). Magnesium-ibogaine therapy in veterans with traumatic brain injuries. Nature medicine, 30(2), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02705-w