New Survey Helps Answer Those Questions

LOS ANGELES — This city is home to the largest VAMC in the nation, as well the single largest population of U.S. veterans. Yet about 4,000 of the vets who call Los Angeles home actually have no home.

To better understand the experience of homelessness and obstacles that homeless veterans encounter in achieving permanent housing, RAND Corp. turned to those who knew the situation best—those who were experiencing it firsthand.

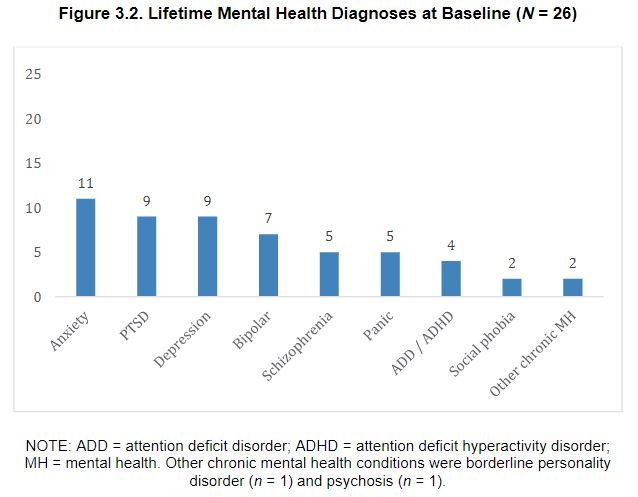

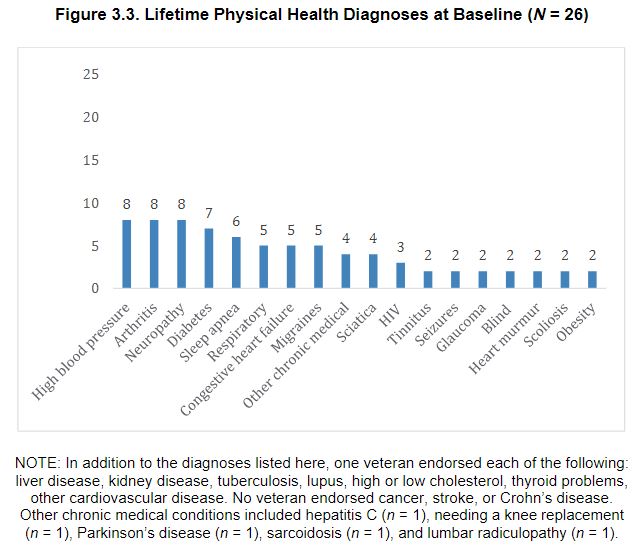

“We wanted to hear directly from veterans living on the West Side of Los Angeles why or why they had not obtained housing, to figure out some of the challenges that they faced by talking them with directly,” said Sarah Hunter, PhD, senior behavioral scientist and director of the RAND Center on Housing and Homelessness in Los Angeles. Hunter led the study which followed 26 veterans—22 men and four women, of whom two were caring for children—experiencing homelessness with the goal of gaining insight that could help those 26 as well as the estimated 4,000 other homeless veterans in Los Angeles. The study was conducted in collaboration with the University of Southern California Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.1

“What was kind of unique about our study is we didn’t interview veterans once. We enrolled them in a yearlong study,” said Hunter. “Our goal was to meet with them once a month in person to see what services they had received since our last visit, whether they had obtained housing or not, why and why not, and to find out more about their health and wellbeing.”

Of the 26 veterans, 11 completed every interview and 75% completed nine or more of them. The COVID-19 pandemic, which began halfway into the study, complicated the interview process but ironically helped some of the veterans with housing, at least short term. “There was a quick mobilization due to FEMA resources to obtain hotel and motel rooms and place people who were homeless into these rooms temporarily,” Hunter said. Five of the vets got into that program.

Over the course of the year, 17 of the 26 veterans in the study sample received some kind of stable housing. The most surprising and disheartening finding for Hunter was that by end of the study only three of the veterans had found permanent housing.

Dispelling Myths

While there are myths that veterans experiencing homelessness (VHE) don’t want to be housed, the interviews indicated that was not the case, said Hunter. “We asked what was their most important life goal at that time and most reported becoming housed. Most of them wanted housing, but it’s important to note that many had become disillusioned with becoming housed. Most were not confident in their ability to obtain housing.”

Some of the noted obstacles to obtaining housing were an inability to navigate the system or a lack of housing options that aligned with their housing preferences, respecting their need for autonomy, privacy, safety or security, Hunter said. “They would rather live on the street than stay in shelter, for example,” she said. “That was elevated with the pandemic. They were really concerned because they were worried about their health.”

While this study shed light on some important barriers to housing it also reinforced the importance of housing for one’s health and well-being. Among the outcomes examined, there was evidence that symptoms of distress, depression and psychosis, as well as quality of life and social support, were better in the months veterans were stably housed than in those months they were not.

Based on the findings, the authors made a number of recommendations to improve access to housing. They include:

- Aligning housing options with veteran’s housing preferences. More research is needed to better understand the housing and service preferences of VEH.

- Opening up services to the most vulnerable veterans. Some of the VEH reported having other than honorable discharge and criminal justice system involvement, which increases the hurdles they face in obtaining access to the VA system of care and, more broadly, housing services.

- Identifying ways systems can more efficiently house veterans, which involve further evaluation of the timelines from initial entry into the homeless services system to exit, in order to look for bottlenecks, gaps and ways to support more efficient access to permanent housing solutions.

- Strengthening services to connect veterans with both formal and informal supports outside of LA. Training and policies need to be put in place so that outreach workers have the resources they need to successfully help people reconnect with loved ones living outside the region, including across state lines.

Other recommendations include allocating more resources to fully meet the needs of veterans in Los Angeles (including more-robust outreach services, substance use disorder treatment and other health care treatment), implementing additional temporary and permanent housing solutions and building in accountability measures to make progress toward these goals more transparent to a larger audience.

The hope is that findings will prompt changes in what is both a social and public health issue. “I think there could be more effort, more support given to these veterans given what we learned,” Hunter said.

The authors say the report should be of interest to entities serving populations including governments, heathcare organizations, practitioners, advocacy groups, researchers and others interested in addressing the homelessness crisis.

- Hunter, Sarah B., Benjamin F. Henwood, Rajeev Ramchand, Stephanie Brooks Holliday, and Rick Garvey, Twenty-Six Veterans: A Longitudinal Case Study of Veterans Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles, 2019–2020. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp., 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1320-1.html.