Study Drills Down to Determine Younger Marines, Soldiers Most at Risk

SEATTLE— Military servicemembers transitioning to civilian life might have some issues in common, but they also differ in many ways, including age, education levels and branch of service. A new study suggested that those differences can help explain why suicide risk varies so greatly among recent veterans.

The study in JAMA Network Open also posited that more granular awareness of military service and demographic characteristics can help identify those most at risk for suicide to better target prevention efforts.1

The research, led by the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, was in the form of an observational study which investigated demographic and military service characteristics associated with suicide risk among U.S. veterans after the transition from active military service to civilian life.

“Although interest is high in addressing suicide mortality after the transition from military to civilian life, little is known about the risk factors associated with this transition,” study authors pointed out.

The retrospective population-based cohort study obtained demographic and military service data from the VA/DoD Defense Identity Repository and included information on those who served on active duty in the US Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps or Coast Guard after Sept. 11, 2001, and who separated from active status between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2017. Data analyses were conducted from Sept. 9, 2019, to April 1, 2020.

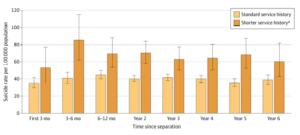

Suicide Rates Conditioned on Time Since Separation by Length of Service With 95% CIs a Shorter service history defined as less than 2 years of service in the active component with no other military service or deployment history.

Researchers focused on suicide mortality within six years after separation from military service in the study, which involved nearly 1.9 million servicemembers. The cohort was 84.1% male with a mean age at military separation of 30.9.

By the end of the six-year study period, 3,030 suicides had been documented in 2,860 men and 170 women.

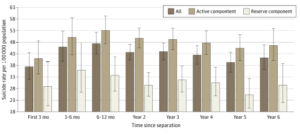

The authors noted that statistically significant differences in suicide risk were determined using demographic and military service characteristics. For example, they reported that suicide rates after separation were time dependent, using reaching their highest point about 6 to 12 months after separation and declining only slightly across the study period.

In addition, male servicemembers were found to have a statistically significantly higher hazard of suicide than their female counterparts (hazard ratio [HR], 3.13; 95% CI, 2.68-3.69). That trend also was true with younger individuals—aged 17-19 years; HR, 4.46 [95% CI, 3.71-5.36])—who had suicide hazard rates approximately 4.5 times higher than those who transitioned at an older age (i.e., 40).

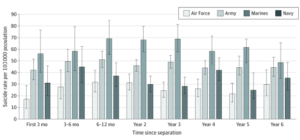

Researchers also documented that service branch remained a significant risk factor for suicide even six years after separation. The study pointed out that those who separated from the Marine Corps (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.36-1.78) and the Army (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.31-1.67) had a higher hazard than those who transitioned from the Air Force.

Furthermore, the suicide risks for those who separated from the active component was higher than for those who separated from the reserve component (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18-1.42). Length of service also was a factor, researchers advised, with servicemembers with a shorter length of service having a higher hazard (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11-1.42) than those with a longer service history.

“Results of this study show that not all service members who recently transitioned from military life had the same risk of suicide,” the authors emphasized, adding that those who were male, were younger, had shorter length of service, or were separated from the Marine Corps or Army had a higher risk of suicide after separation.

“Findings of this study suggest that suicide rates increase after transition to civilian life and that awareness of demographic and military service characteristics may help prevent suicide among veterans who are most at risk,” the researchers concluded.

Background information in the article noted that rates of suicide in the U.S. military have increased substantially since the early 2000s. Separation from military service has been identified as an especially fraught milestone which can affect social support and financial security, as well as create changes in access to healthcare, including mental healthcare.

At the same time, the authors wrote, “national interest is high in understanding the association of military separation with suicide among service members.” They cited d the VA’s 2018 to 2028 National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide, which highlights this critical need among those who have recently transitioned from military service, as well as a 2018 Presidential Executive Order which sought to improve suicide prevention services for veterans going back to civilian life.

Suicide Prevention Efforts

“Despite these national programs, almost no data are available to guide suicide prevention efforts targeted at these particular servicemembers. Increased risk of suicide has generally been associated with military separation,” the researchers pointed out, however.

Even though past research has found that the hazard rate of suicide was about 2.5 times higher for veterans within the first year of separation than for the active duty population, “more data are needed to determine which individuals in the transitioning cohort are at high risk and when that risk is highest. To our knowledge, despite the national interest in this problem, no study has comprehensively examined time-varying associations of suicide with transition to civilian life,” according to the study.

The result was the current population-based cohort study, which was touted as the first to examine specific suicide risk factors by time since transition from active status.

“This study showed that suicide rates followed a nuanced pattern after individuals left the military,” the authors reported. “The highest suicide rates were observed in year 1, but they increased over the first 6 months and generally peaked in the 6 to 12 months after separation. This pattern was true for servicemembers who left the Army, Marine Corps, or Air Force; the rates for those who last served in the Navy peaked 3 to 6 months after their transition.”

Researchers posited that psychosocial stressors would increase in year 1 after separation and, in support of that view, determined that, “compared with recently transitioned service members with a bachelor’s degree, those with fewer years of education (i.e. high school or non-high school graduate) had a higher hazard of suicide. These individuals may have had a more difficult time finding postmilitary employment, thereby exacerbating their financial concerns, difficulties establishing health care, and attendant psychosocial stressors (and, therefore, suicide risk).”

The authors added that pre-enlistment characteristics, experiences during military service or experiences after separation also could have contributed to the results

“Study findings suggested that, within the high-risk cohort of transitioning service members, suicide prevention resources are especially important in the first year and remain important for at least 6 years given that the rates did not decline substantially within the study period,” they wrote.

The study also was the first to examine rates by service branch in the first six years after separation from military life, with suicide hazard rates for veterans of the Army and Marines Corps calculated as 1.5 times higher than the rates for Air Force or Navy veterans. “Compared with the other branches, the Marines Corps had the highest crude suicide rate every year after transition,” the researchers advised. “It is unclear which factors were associated with these rate differences. Each branch has a unique culture, training experiences, deployment experiences, and demographic compositions. The branches may also recruit service members who are unique in some ways. Many veterans continue to strongly identify with their branch even after leaving the service.”

Military component was another risk factor during the transition period. While previous studies have raised concerns about mental health challenges with reservists, this study suggested that active-duty status is more linked to suicide risks. “We speculated that citizen soldiers in the reserve component, who often maintain civilian employment and considerable ties to their civilian life, would experience fewer transition adjustments, but this possibility requires additional study,” according to the report.

Acknowledging that military personnel with an enlistment of less than two years usually have a separation related to an injury, medical condition, mental health problem, discipline or legal issue, study authors found their suicide rate to be especially high—increasing from the first three months when it was already high (53.2 suicides per 100 000) to 3 to 6 months after transition (85.2 suicides per 100 000) when it peaked.

Young age also was linked to greater suicide risk, according to the researchers, with non-Hispanic White male veterans with less education and divorced individuals having higher suicide rates than their respective demographic comparison groups.

- Ravindran C, Morley, SW, Stephens BM, Stephens BM, Stanley IH, Reger MA. Association of Suicide Risk With Transition to Civilian Life Among US Military Service Members. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2016261. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16261