Click to Enlarge: Social determinants of health among noncitizen deported US veterans: A participatory action study Source: PLOS Global Public Health

RIVERSIDE, CA — For noncitizen U.S. military servicemembers, deportation can increase the risk of poor physical and mental health outcomes, making this group a vulnerable and often overlooked health disparity population, according to a recent study.

The qualitative study published in PLOS Global Public Health examined the effects of deportation on the health and well-being of noncitizen veterans who served in the U.S. military. The study also identified solutions to address the healthcare needs of deported U.S. veterans.1

While military service provides a “pathway to U.S. citizenship, it doesn’t guarantee automatic citizenship or guard against deportation,” study authors explained. The U.S. Congress has provided a pathway for noncitizen servicemembers serving honorably in the U.S. military during wartime and recently in peacetime to apply for citizenship, but “less than 50% of eligible servicemembers naturalize during military service. Servicemembers mistakenly leave the military believing they are naturalized U.S. citizens and only realize this isn’t true after they’re discharged and don’t have the protections that accompany citizenship,” the researchers added.

The transition from the military to civilian life can be difficult for many veterans after discharge, but it’s especially challenging for noncitizen veterans. Since the mid-1990s, the U.S. has “deported thousands of noncitizen veterans, including those who committed misdemeanors such as disorderly conduct or drunk driving. Eighty percent of deported veterans report medical issues, and 75% lack access to healthcare after deportation. Individuals of Mexican and Central American origin are overrepresented in this population,” the researchers pointed out.

Noncitizen U.S. military veterans, particularly those with mental health and substance abuse disorders, are at increased risk for deportation based on the current military, criminal justice and immigration policies. Unless changes are made in the nation’s policies, they will “continue to present in the immigration system and face deportation charges,” the study authors suggested.

The 12 study participants were noncitizen U.S. military veterans who had lived in California and were deported to Tijuana, Mexico. The researchers collaborated with the Deported Veteran Support House (DVSH) to recruit participants into the study. They drove to Tijuana to speak with deported veterans who were accessing free mobile medical services through Healing Hearts Across Borders and agreed to be involved in the study. Some of the participants recruited other veterans in their network, the authors wrote in an email.

Eligible participants met the following criteria: at least 18 years of age, U.S. veterans of any service era, Mexican citizens by birth, U.S. residents for at least 10 years, deported to Mexico in the last 20 years and currently residing in Tijuana. All of the participants were men, and most had been born in Mexico and spent the majority of their life in the U.S., often from childhood. The analysis, conducted from December 2018 to January 2019, involved a sociodemographic survey, photo elicitation and semi-structured interview, according to study authors.

“We found that deportation acts as a social determinant of health, meaning that it increases risk for poor physical and mental health outcomes,” Ann Cheney, PhD, an associate professor of social medicine, population and public health in the School of Medicine at the University of California, Riverside, told U.S. Medicine. “Our study findings are the first to report on the qualitative experience of deportation and its effects on physical health (chronic health conditions) and mental health (depression and loneliness).”

Traumatic Experience

“Deportation is a significant traumatic experience and non-U.S. citizen veterans feel rejected by their country when this occurs,” Cheney said. “Yet, at the same time, they remain loyal to the country they served and the citizens they fought to protect. Healthcare providers’ recognition of their contribution to protect freedom is important for these patients.”

“Our analysis of their photos and narrative text indicates that deportation caused them social, economic and political insecurities,” Cheney explained in a press release issued by the University of California, Riverside about the study. “We found that after they were deported from the U.S., these veterans struggled to maintain access to necessities. With disruptions in their social networks and the removal from the country many considered home, they experienced chronic stress and poor health outcomes.”

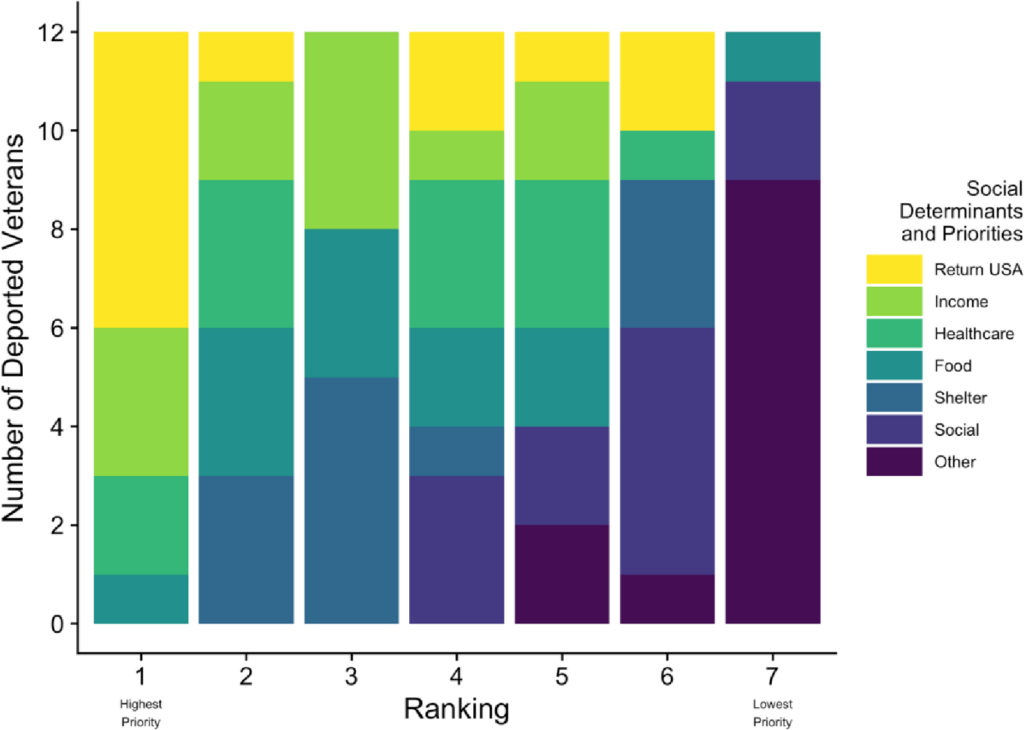

The press release added that “poor physical and mental health and the effects of combat-related violence and trauma can increase homelessness, strained interpersonal relationships, substance use, legal trouble and difficulty in maintaining employment.” The study authors reported that “veterans prioritize returning to the United States to improve their quality of life.”

The study didn’t find major differences in the participants based on socio-demographic characteristics, such as sex, race and age. Military service era could have affected the participants. For instance, “younger veterans who served in the Iraq and Afghanistan-era had more recent experiences of transitioning from military to civilian life and the psychological challenge of making that transition,” the authors explained.

The project was led by a medical student and public policy student who were interested in veteran issues and knew of Cheney’s previous research with veterans in Arkansas and her current work in Latinx immigrant populations. Because of Cheney’s expertise, they asked her to mentor them on the research study.

For healthcare professionals who want to help address the physical and behavioral health issues of noncitizen veterans who were deported, “this patient population needs access to healthcare services and mental health services, in particular,” Cheney advised.

“They have limited financial resources and cannot cross the border,” Cheney said. “They need access to free telemental health and telehealth more generally. Partnerships with healthcare providers in Mexico who can provide direct patient care that is free and accessible in English is needed.”

To solve these issues for deported noncitizen veterans, a change to immigration policy is needed, Cheney explained. Because these veterans served in the U.S. military, “their legal status should be prioritized, and there should be an avenue for them to obtain permanent residency and citizenship if they want that,” she added.

“Military leaders also need to know where to send servicemembers who need support navigating the legal system, and they should encourage their servicemembers to access these services early on in their military career,” Cheney recommended.

The study also suggested “modifying veteran reintegration programs, as well as reforming criminal justice and immigration laws, such as creating more Veteran Treatment Courts and allowing immigration judges to consider military history during deportation proceedings involving noncitizen veterans.”

“Without change in our nation’s policies, noncitizen veterans will continue to be present in our immigration system and face deportation charges,” Cheney said in the press release. “Attention needs to be urgently paid to addressing behavioral health conditions in this population. In Mexico, deported veterans need to be trained to speak Spanish and develop skills needed for employment. They also need immediate access to free healthcare services, specifically mental healthcare services, to cope with loss, grief and isolation linked to the trauma of deportation.”

- Tao F, Lee CT, Castelan E, Cheney AM. Social determinants of health among noncitizen deported US veterans: A participatory action study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023 Aug 2;3(8):e0002190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002190. PMID: 37531350; PMCID: PMC10396001.