Thomas Osborne, MD, of the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System and Stanford University School of Medicine

PALO ALTO, CA — Environmental heat can adversely affect health, resulting in heightened healthcare demands, disability and even mortality. The combination of particular medical conditions with the ongoing global temperature increase may exacerbate susceptibility to heat-related ailments.

A new study by VA researchers uncovers important and concerning trends in heat-related illness (HRI) and identifies populations most vulnerable to these conditions.

Scientists led by Thomas Osborne, MD, of the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System and Stanford University School of Medicine conducted a longitudinal respective analysis of routinely collected patient data from the VHA’s national electronic health record database from Jan. 1, 2002, through Dec. 31, 2019. They assessed HRI diagnoses for associations with patient demographic, comorbidities and geographic residence at the time of the heat-related illness diagnosis and used descriptive statistics, linear regression and additive seasonal decomposition methods to assess risk factors and trends.1

The study, which was published in the Journal of Climate Change and Health, had three key findings, Osborne said. “The first is that heat-related illnesses have been steadily increasing in our veteran population over the 18 years that we assessed,” he said. “The second is that the health outlook is worse for people with preexisting health conditions and some specific demographic groups of people.”

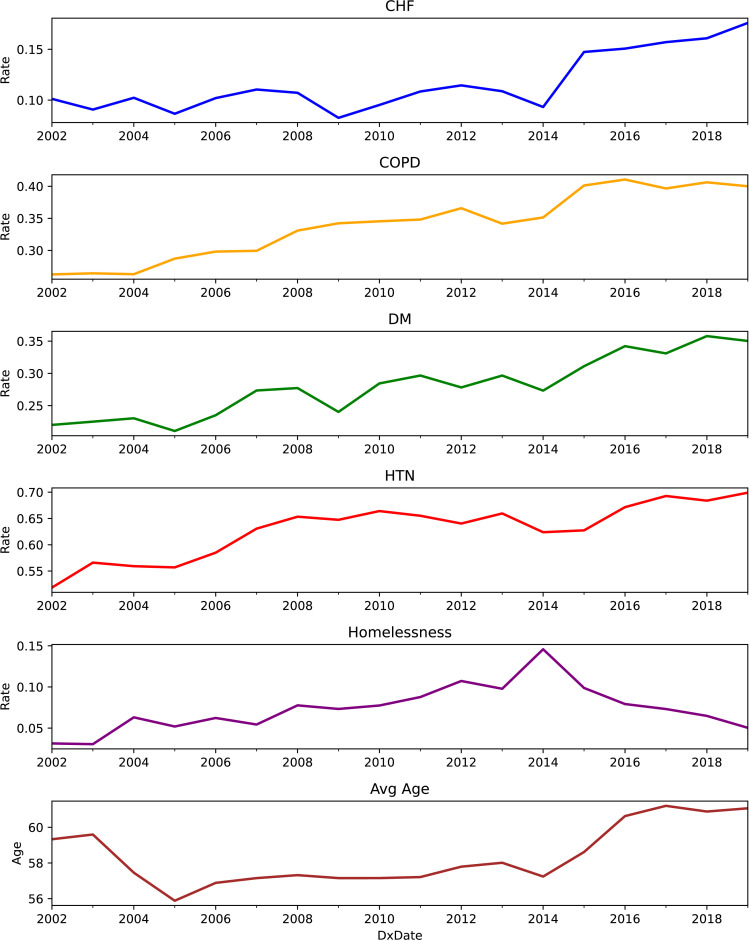

Click to Enlarge: Rate of common chronic conditions, homelessness and average age for Veterans diagnosed with HRIs over our assessment period. *Congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes-mellitus (DM), and hypertension (HTN). Source: The Journal of Climate Change and Health

The study found risk of HRI disproportionately increased both among veterans with underlying health conditions a whole and among those with specific common conditions—congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension—examined separately by the study and that Black and American Indian/Alaska Native Veterans were more likely to be diagnosed with HRI than white veterans.

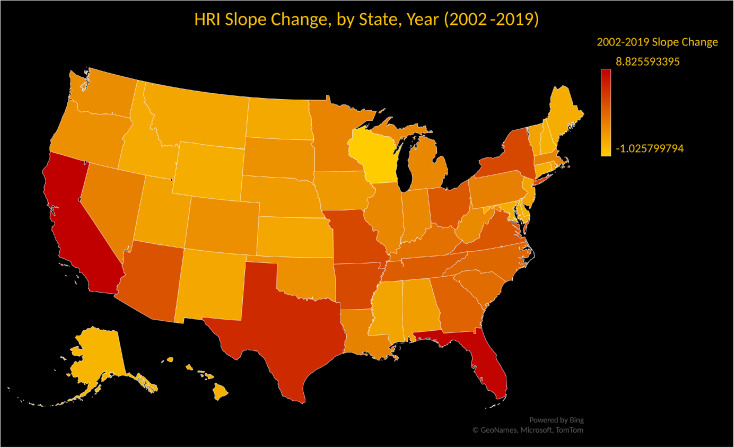

The third important finding was that no state was immune from the problem but that the rate was different for different states across the U.S., Osborne told U.S. Medicine. For example, there were notable increases in HRI diagnoses in Missouri, Arkansas, Virginia, Ohio and New York; however, some typically warmer U.S. states, such as New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Louisiana, did not have a dramatic increase in their overall HRI diagnoses over the assessment period.

“I was expecting that uniformly it would almost look like bands across the U.S., with southern states having the biggest challenges and the biggest increase in heat-related illnesses and the northern states would be low, and it would be a simple gradation. But it wasn’t,” Osborne said. “And so typically warmer states actually had lower incidence of heat-related illness than the other and vice versa. It was more heterogeneous than we expected. That was a surprise, but we have some ideas why that was happening.”

One potential explanation the researchers offered was that people and programs in traditionally warmer states have already adopted policies, procedures and practices that effectively mitigate the negative health consequences of environmental heat. However, some locations, that do not traditionally or as commonly experience hot weather, might not be as prepared during an extreme heat event.

Lessons Learned From Homeless Vets

Click to Enlarge: Heat map of all 50 US states and District of Columbia. Color density corresponds with slope change of HRI diagnoses over our assessment period (Table S1) (red = larger positive slope, followed by orange, and the least slope change in yellow). Source: The Journal of Climate Change and Health

Another observation from the study was that the rate of HRI in the homeless veteran population rose in the first half of the assessment timeframe and decreased over the second half. Although the study did not identify a specific cause for the drop, the authors speculated the results might be related to veteran homeless health and wellness programs being initiated and expanded upon during this time of increasing environmental temperature. “It is likely that, when these programs take care of the whole person—finding them shelters and homes and jobs and everything else, that reduced the risk,” Osborne said.

Although the study’s findings overall are concerning, Osborne said there is also evidence or suggestions in their assessments that there are efforts—such as programs for homeless veterans—that have an impact. “So we are hoping there are things we can do to turn the tide and reduce heat-related illness.”

In the more immediate future, he hopes the study will serve as “a touchstone, a way to beginning a discussion of the risks with patients—especially the most vulnerable patients—that can foster healthier outcomes.”

Clinicians could discuss with patients the importance of proper hydration and the warning signs of being overheated and what they can do to if they experience those signs, he said. Patients can make plans for hot days—such as avoiding parked cars or outside work on hot days—or taking advantage of malls or cooling centers when temperatures rise.

“The more we can be prepared and proactive, the more likely the fewer people will have bad things happen,” he said.

- Osborne, T. F., et al. (2023). Trends in heat related illness: Nationwide observational cohort at the US department of veteran affairs. The Journal of Climate Change and Health. doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100256.