Joint House VA, Military Subcommittee Hearing Tackles Issue

WASHINGTON—In a rare joint hearing by the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Military Personnel and VA Subcommittee on Health, legislators examined how DoD and VA are working to address the increase in veteran suicides.

“We must treat the suicides of active duty serivcemembers and the suicide of veterans as intrinsically linked,” explained Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA), chairman of the Subcommittee on Military Personnel. “Military service appears to be a casual pathway for increased suicide risk due to the access to and familiarity with firearms, PTSD, depression, loss of community, alienation, head injuries and substance dependence.”

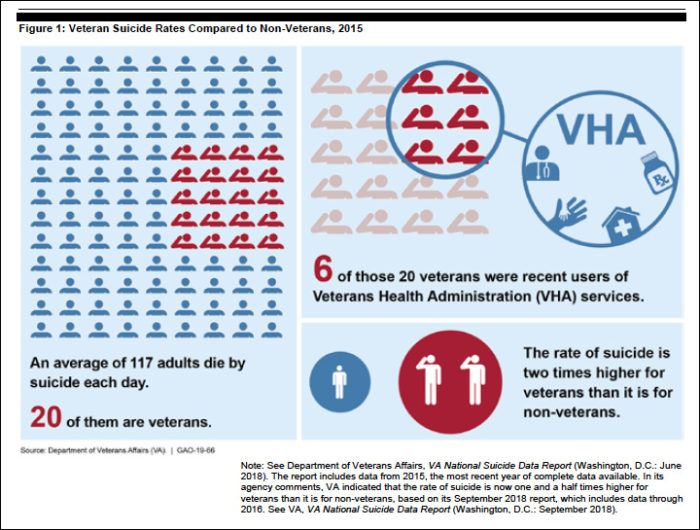

Suicides among veterans ages 18 to 34 have steadily increased over the last decade, rising 32% between 2005 and 2016, with a jump of more than 10% from 2015 to 2016. Meanwhile, the military saw a total of 321 active-duty servicemembers take their own life in 2018—the highest rate in at least six years. The services began actively tracking suicides in 2001.

Asked about the cause of last year’s high suicide rate in the military, Capt. Mike Colston, MD, DoD’s director of mental health policy and oversight, said he didn’t know. “Obviously there is a disturbing secular trend. We have seen our suicide rate double between 1999 and 2016, while the secular rate increased 25% in every state. When I was an intern, the suicide rate was low. Military service was protective for suicide. Obviously some sort of circumstances have changed.”

His colleague, Elizabeth Van Winkle, PhD, DoD’s director of force resiliency, who oversees the Defense Suicide Prevention Office, agreed, noting there is never one root cause for suicide.

“It is an intersection of a variety of factors—social, biological and psychological—that operate at the individual, community and societal levels. It’s fairly complex and often difficult to determine exactly what is occurring within a population or even a subpopulation.”

One thing Colston could say with some certainty is that the stigma surrounding mental health issues is pervasive among servicemembers and has a significant impact on whether or not they seek care. The services see spikes among servicemembers seeking mental healthcare during their last year of deployment, Colston explained. This suggests that, even though they were struggling with mental health issues, servicemembers were worried about seeking care earlier because they were afraid it would impact their career.

Getting the Word Out

“We need to get the word out that it’s almost impossible to lose your security clearance by endorsing a mental health history on your [national security clearance questionnaire],” he said. “We really have data. Only a couple dozen out of 10 million security clearances [have ever been impacted].”

DoD has made efforts to normalize behavioral health for servicemembers by embedding behavioral health providers in primary care clinics and in line units, Colston said. The presence of a psychiatrist deploying with a unit is important not only in destigmatizing mental healthcare, but in providing line commanders with a better understanding of the mental wellbeing of their troops.

But on both the VA and DoD side, there’s agreement that providing mental healthcare will not be enough to stem the rising tide of suicides.

“There are probably 12 evidence based treatments for suicidal folks,” Colston explained. “The thing we struggle with is that they have really small effect sizes, so you need to treat a lot of people to really help one person become less suicidal. Establishing a nexus between our treatments and a decrease in suicide has been extremely hard, and at the population level we just haven’t seen a signal yet.”

This comes as no surprise to Keita Franklin, PhD, LCSW, VA’s national director of suicide prevention, who sees the best chance of impacting suicide in moving beyond the healthcare arena.

“This issue cannot be solved by mental healthcare alone,” she declared. “National data shows that more than half of Americans who died by suicide in 2016 had no known mental health issue at the time of their death, and this is true of veterans as well. A massive expansion of mental health providers and world class mental health access has done little to reduce the rate of suicides among veterans. VA cannot end veterans’ suicide alone.”

Instead, Franklin is advocating for a set of bundled initiatives that spread across the entire government on the federal, state, and local levels. These initiatives target housing, employment, family support, and the kind of programs that ground a veteran to their community.

“[In addition to mental healthcare] veterans need life supports throughout the course of the week,” Franklin said. “We need to make sure they’re employed, that they have homes, that they’re engaged in a meaningful life that brings them purpose and passion, and that they have the supports to thrive in life above and beyond their mental health therapy.”

She noted that not just any employment would do, especially for men and women who are just coming out of military service.

“Meaningful employment. Not just any random job,” she declared. “[They need] one where they feel they’re part of a mission.”

The complex nature of suicide and the scope of these bundled approaches means that success will not come quickly or in the absence of a sustained, intense effort by everyone involved, Franklin said. “This calls for [these approaches] to be at full force over time. Full throttle. We’ve got to move out with educating every single family member in the nation. There’s 20 million veterans and they all have family members. VA and DoD recognize their role in suicide prevention, but I think there’s work to be done in other sectors. All leaders need to recognize their role in helping with this.”