VAMCs Are Incorporating the New Policies in Pain Management Plans

With a growing realization that post-surgical opioids might be neither the safest nor most effective way to reduce pain, VA facilities are using a variety of non-opioid painkillers to help patients manage their discomfort after undergoing surgery. In fact, opioids are no longer considered first line treatment for most types of acute pain, including that related to surgery.

STANFORD, CA — For at least a decade, VA has been grappling with how to reduce long term opioid prescriptions for veterans with chronic pain. One result was the VA’s Opioid Safety Initiative, which has reduced long term opioid dispensing more than 50%.

STANFORD, CA — For at least a decade, VA has been grappling with how to reduce long term opioid prescriptions for veterans with chronic pain. One result was the VA’s Opioid Safety Initiative, which has reduced long term opioid dispensing more than 50%.

Another area where opioids are widely used—and suspected of being overprescribed—is in the short term treatment of pain after surgery, although that has received less focus until recently. It has been suggested that receiving postsurgical opioids can be a risk factor in becoming dependent on the painkillers over a more extended period of time.

One gamechanger has been recent research finding that managing pain with opioids doesn’t necessarily improve surgical outcomes. The bottom line: Opioids are no longer considered first-line treatment for most types of acute pain, including that associated with surgery, according to a prescribing guide.

Why that is occurring is partly explained by a study last year in the American Journal of Surgery, which sought to describe variation in perioperative opioid exposure and its effect on patients’ outcomes.1

The study, led by researchers from Stanford University and the VA Palo Alto Health Care System, looked at perioperative exposure to morphine and its association with postoperative pain and 30-day readmissions.

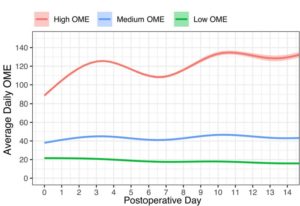

To do that, the study team used nationwide VHA data on high-volume surgical procedures from 2007-2014, identifying 235,239 veterans undergoing orthopedic, general or vascular surgery. They categorized the participants into three categories:

-

5.4% of them were considered high trajectories (116.1 oral morphine equivalents (OME) per day),

-

53.2% as medium trajectories (39.7 OME/Day), and

-

41.4% as low trajectories (19.1 OME/Day).

Surprising results suggest that patients in the high OME group had higher risk of a pain-related readmission (OR: 1.59; CI: 1.39, 1.83) compared to the low OME trajectory.

“In conclusion, patients receiving high perioperative OME are more likely to return to care for pain-related problems,” the researchers wrote.

Because of increased understanding of growing risks and possibly shrinking benefits for opioid analgesics, a website for VHA Pain Management pointed out that the approach to acute and postsurgical pain has been changing in the healthcare system. “Opioids may not be the most effective or safest approach in many situations, and when opioids are used they should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest indicated duration,” according to the advice for providers. “Even when opioids are used short term, the risks of short-term therapy becoming long-term therapy increases with longer duration and higher doses of opioid therapy. Current guidelines and recent evidence recommend multimodal treatment of acute pain and use of non-pharmacologic options and nonopioid pharmacologic options as first-line therapy with opioids added when necessary.”

In an effort to implement the changes, the spotlight had been on surgeons. An international review earlier this year in Frontiers of Surgery discussed the opioid crisis and the role played by surgeons, pointing out, “Over the past two decades, there has been a sharp rise in the use of prescription opioids. In several countries, most notably the United States, opioid-related harm has been deemed a public health crisis. As surgeons are among the most prolific prescribers of opioids, growing attention is now being paid to the role that opioids play in surgical care.”2

The article called for greater scrutiny of pain management prescribing practices, while also conceding that opioids might sometimes be necessary to provide patients with adequate relief from acute pain after major surgery. “We draw attention to the mounting evidence that preoperative opioid exposure places patients at risk of persistent postoperative use, while also contributing to an increased risk of several other adverse clinical outcomes,” the authors wrote.

Nonopioid Analgesics

American Society of Anesthesiology guidelines strongly urge that, whenever possible, anesthesiologists should use multimodal pain management therapy, including medications such as acetaminophen COX-2 selective NSAIDs, or COXIBs, nonselective NSAIDs, and calcium channel α-2-δ antagonists such as gabapentin and pregabalin should be considered as part of a postoperative multimodal pain management regimen.3

Those can be combined with regional blockade with local anesthetics, the ASA noted.

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration approved Anjeso (meloxicam injection), which is indicated for the management of moderate to severe pain, alone or in combination with other non-NSAID analgesics. The drug from Baudax Bio is the first once-per-day 24-hour, intravenous COX-2 preferential NSAID, the company said. It was approved based on phase 3 trials in patients who had undergone bunionectomy and elective abdominoplasty surgeries.

How widely multimodal postoperative treatment is being used at VA hospitals isn’t clear, with a recent study of a single university-affiliated VA hospital finding the new technique for perioperative pain management is being used but could be improved.

The report in the journal Pain Medicine noted that previous studies have found substantial variability in its utilization. The authors from the VA Palo Alto Health Care System and Stanford University sought to better understand the factors that influence anesthesiologists’ choices. To do that, they assessed the associations between patient or surgical characteristics and the number of nonopioid analgesic modes received intraoperatively across a variety of surgeries.

Included were elective inpatient surgeries—orthopedic, thoracic, spine, abdominal and pelvic procedures—that used at least one nonopioid analgesic within a one-year period. Results indicated that, of the 1,087 procedures identified, 33%, 53%, and 14% were managed with one, two and three or more modes, respectively.

The study found that older patients had lower odds of receiving three or more modes (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.15-0.52), as were patients with more comorbidities (two modes: aOR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.79-0.96; three or more modes: aOR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.71-0.94).

While utilization varied across types of surgery, the research demonstrated that increasing the number of modes, particularly use of regional anesthesia, was associated with shorter length of stay.

“Our study suggests that age, comorbidities, and surgical type contribute to variability in MMA utilization,” the authors wrote. “Risks and benefits of multiple modes should be carefully considered for older and sicker patients. Future directions include developing patient- and procedure-specific perioperative MMA recommendations.”

- Hernandez-Boussard T, Graham LA, Carroll I, et al. Perioperative opioid use and pain-related outcomes in the Veterans Health Administration [published online ahead of print, 2019 Jun 28]. Am J Surg. 2019;S0002-9610(19)30581-1. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.06.022

- Shadbolt C, Abbott JH, Camacho X, et al. The Surgeon’s Role in the Opioid Crisis: A Narrative Review and Call to Action. Front Surg. 2020;7:4. Published 2020 Feb 18. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2020.00004

- Practice Guidelines for Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative Setting: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 2012;116(2):248-273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1030.

- Kwong JZ, Mudumbai SC, Hernandez-Boussard T, Popat RA, Mariano ER. Practice Patterns in Perioperative Nonopioid Analgesic Administration by Anesthesiologists in a Veterans Affairs Hospital. Pain Med. 2020;21(2):e208‐e214. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz226