Fear of Withdrawal Symptoms Fuels Drop Outs

A common explanation for the high dropout rate and failure of a substance use disorder program is that patients fear symptoms of opioid withdrawal. A new study suggested that is for good reason, especially since patients who are exposed to full opioid agonists chronically are recommended to already be experiencing moderate withdrawal symptoms before they can get drugs to alleviate the symptoms. That’s why the FDA has approved new alternatives, including auricular stimulators, to help patients through the difficult withdrawal symptoms.

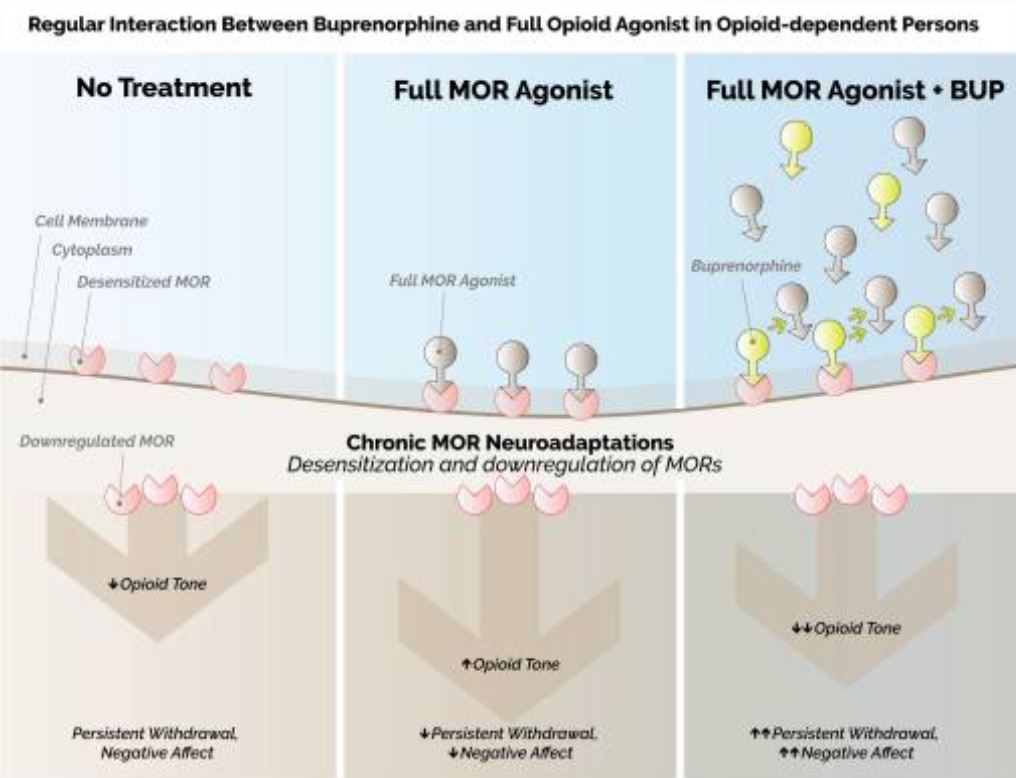

Click To Enlarge: Regular interaction between buprenorphine (BUP) and full mu-opioid receptor (MOR) agonists in opioid-dependent persons. Left: chronic opioid use leads to a host of neuroadaptations at the MORs, including MOR desensitization and downregulation. These neuroadaptations are manifested clinically as a reduced opioid tone, leading to persistent opioid withdrawal, and a pervasive negative affective state. Center: full MOR agonists may temporarily increase the opioid tone, reducing opioid withdrawal and negative affect. However, the chronic MOR neuroadaptations persist, such that MORs remain desensitized and downregulated. Right: BUP is a partial agonist at the MOR, with low intrinsic efficacy but very high affinity. Since the affinity of BUP for the MOR is greater than that of full MOR agonists, and given its slow dissociation half-life, BUP may continue to displace full opioid agonists from MOR for up to 24–48 h after its dosing. Importantly, as BUP displaces full opioid agonists from MOR that are already downregulated and desensitized by chronic opioid use, this results in a profound reduction of MOR activity, thereby increasing the likelihood of precipitated withdrawal Source: Clin Drug Investig. 2021; 41(5): 425–436.

WASHINGTON, DC — In their shared clinical guidelines, the VA and DoD strongly warn against initiating opioid withdrawal management without a plan for ongoing pharmacotherapy management.

Why? What the guidelines call “high risk of relapse and overdose.” For good reason, patients fear symptoms of opioid withdrawal. And, with short-acting opiates, those symptoms—nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, drug cravings, depression, anxiety, irritability—can occur as soon as six hours after the last dose, while extended-released might take 30 hours. Peak discomfort often occurs around three days after the last dose.

An increase in the availability of buprenorphine (BUP) has extended the capacity of healthcare systems to treat persons with OUD, but authors of a recent study published in Clinical Drug Investigation pointed out, however, “The initiation—or induction—of pharmacotherapy with BUP, however, still presents a considerable challenge: due to its low intrinsic activity at the [mu-opioid receptor] MOR, combined with its capacity to displace agonists from the MOR, BUP has the potential to acutely precipitate opioid withdrawal. Multiple studies have demonstrated that precipitated withdrawal during induction onto BUP occurs commonly, especially when it is preceded by recent exposure to full opioid agonists—such as methadone or heroin—which is very often the case among persons with OUD.”

Adding to the issue, according to the authors from the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven and Yale University in New Haven, CT, is that long-term OUD treatment outcomes, such as retention in the program and abstinence from nonmedical usage can be affected.1

That creates a difficult dilemma, they noted, because “patients who are exposed to full opioid agonists chronically are recommended to already be experiencing moderate withdrawal symptoms at the time of induction.”

A recent study protocol helped explain current thinking on opioid use disorder, while making it clear that the best way to treat it remains a work in progress.

Researchers also from the VA Connecticut Healthcare System Yale School of Medicine recounted that the United States announced a national epidemic and public health emergency in October 2017 because of the increase in heroin and fentanyl use and the dramatic jump in opioid overdose deaths, including among veterans. Opioid overdoses claimed more than 47,000 victims in the U.S. from October 2018-19, the authors pointed out in Addiction, Science & Clinical Practice, and early data from 2020 signaled that overdose deaths continued to rise during the COVID-19 pandemic.2

The authors advised that the number of veterans diagnosed with OUD and seeking VHA treatment rose significantly in the past few years; a 131% increase in OUD diagnoses was recorded from 2001 (27,840 cases of OUD) to 2015 (64,373 cases), with 69,142 veterans diagnosed with OUD in fiscal year 2017, jumping to more than 80,000 now. “As in the general population, OUD among veterans is associated with housing instability, mental health diagnoses, suicide, and criminal justice involvement,” they wrote.

The study emphasized, “The most effective treatment for OUD are medications of three types: the full opioid agonist methadone, the partial agonist buprenorphine, and the antagonist naltrexone in extended-release injectable formulation (XR-NTX).” But relapse rates are high. The study cited several reviews indicating that buprenorphine retention at six months is estimated at less than 40%. A review last year reported retention rates falling from 58% at six months to 38.4% at three years.2

The research team had designed their study, “Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder in Veterans (VA-BRAVE)” a 52-week randomized controlled study to compare the effectiveness of the long-acting monthly injectable formulation of buprenorphine versus the standard of care sublingual formulation, administered as part of routine outpatient care to 952 Veterans across 20 sites in the VHA.

Unfortunately, before the trial was initiated, the worldwide pandemic occurred, and the authors had to determine how to proceed while protecting participant and staff safety. The study was recruiting early this year.

Auricular Stimulators

New guidelines from the VA and DoD do not include information on noninvasive electrical nerve stimulators, which have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, for the adjunct treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms. The devices are placed behind the ear to stimulate certain cranial nerves with auricular projections and to relieve some of the difficult withdrawal symptoms faced by SUD patients.

In 2020, after two of those had received FDA approval, an article in Bioelectronic Medicine, noted, “The recent opioid crisis is one of the rising challenges in the history of modern health care. New and effective treatment modalities with less adverse effects to alleviate and manage this modern epidemic are critically needed,” adding, “Current experimental evidence indicates that this type of noninvasive neural stimulation has excellent potential to supplement medication-assisted treatment in opioid detoxification with lower side effects and increased adherence to treatment.”3

Northwell Health-led researchers advised that bioelectronic medicine is an emerging field focusing on the use of neuromodulation to provide alternative, nonpharmacological treatments for various diseases. The therapeutic approaches based on vagus nerve stimulation have already generated promising results in several chronic disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, they noted, adding, “The therapeutic utility of noninvasive approaches, including auricular vagus nerve stimulation, is also currently being explored.”

With use of the devices, electrical pulses are generated, delivered to the ear via electrodes. The authors explained that device effects appear to be related to reduction of autonomic symptoms associated with withdrawal from opioids including sweating, gastrointestinal upset, agitation, insomnia and joint pain. Researchers said past studies have shown that the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves can play a role in mediating the response, or that activation of the parasympathetic nervous system can have that effect.

Use of such devices “can ultimately reduce the need for supportive medications and can facilitate smooth transition from detoxification to commencing medication-assisted treatment in opioid dependent patients. This treatment modality has so far been associated with only minor local side effects at the device placement site. While this noninvasive modality appears to be an exciting new opportunity in alleviating the current opioid epidemic, more studies are clearly needed to further validate the potential of this intervention and support its use with the hope of helping our patients and their families,” the authors concluded.

- De Aquino JP, Parida S, Sofuoglu M. The Pharmacology of Buprenorphine Microinduction for Opioid Use Disorder. Clin Drug Investig. 2021 May;41(5):425-436. doi: 10.1007/s40261-021-01032-7. Epub 2021 Apr 5. PMID: 33818748; PMCID: PMC8020374.

- Petrakis, I., Springer, S.A., Davis, C. et al. Rationale, design and methods of VA-BRAVE: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of two formulations of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in veterans. Addict Sci Clin Pract 17, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-022-00286-6

- Qureshi, I.S., Datta-Chaudhuri, T., Tracey, K.J. et al. Auricular neural stimulation as a new noninvasive treatment for opioid detoxification. Bioelectron Med 6, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42234-020-00044-6