Many Possibilities Why Rates Are Higher Than White Veterans

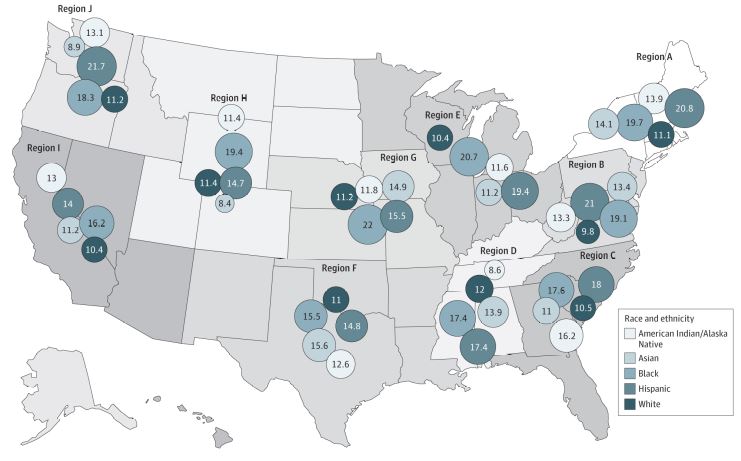

Dementia Incidence Rate by Race and Ethnicity and Region The area of the circles corresponds to the actual value of the rate presented in the circle for each racial and ethnic group. Dementia is defined using a comprehensive list of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and ICD-10 codes recommended by the Veterans Health Administration Dementia Steering Committee. Of the more than 1.8 million Veterans Health Administration patients, who were a mean (SD) age of 69.4 (7.9) years and were followed up for a mean of 10.1 years (median, 10.3; range 0.7-17.9 years), 13% developed dementia.

Region A: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont

Region B: Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia

Region C: Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina

Region D: Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee

Region E: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin

Region F: Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas

Region G: Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska

Region H: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Wyoming

Region I: Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada

Source: Jama Network

SAN FRANCISCO — The incidence of dementia varies significantly by race and ethnicity among older adults receiving care at VHA medical centers, according to a new study. Why that occurs was not immediately clear, however.

The retrospective cohort study of about 1.9 million older VHA patients found that the age-adjusted incidence of dementia per 1,000 person-years over a mean follow-up of 10.1 years was:

- 14.2 for American Indian or Alaska Native participants,

- 12.4 for Asian participants,

- 19.4 for Black participants,

- 20.7 for Hispanic participants, and

- 11.5 for white participants.

After adjustment, San Francisco VA Healthcare System-led researchers report that the hazard ratios compared with white participants were significantly higher in all subgroups except among American Indian or Alaska Native participants.

“The racial and ethnic diversity of the U.S., including among patients receiving their care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), is increasing,” the authors write in JAMA. “Dementia is a significant public health challenge and may have greater incidence among older adults from underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups.”1

The study team sought to determine dementia incidence across five racial and ethnic groups and by U.S. geographical regions within a diverse, national cohort of older veterans who received care in the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States.

The retrospective cohort study used a random sample within the VHA (5% sample selected for each fiscal year) of 1,869,090 participants aged 55 years or older. Records were evaluated from Oct. 1, 1999, to Sept. 30, 2019, which was the date of final follow-up).

Study participants’ mean age was 69.4, and 2% were women. In terms of ethnicity, 0.4% were American Indian or Alaska Native; 0.5% were Asian; 9.5% were Black; 1% were Hispanic; and 88.6% were white.

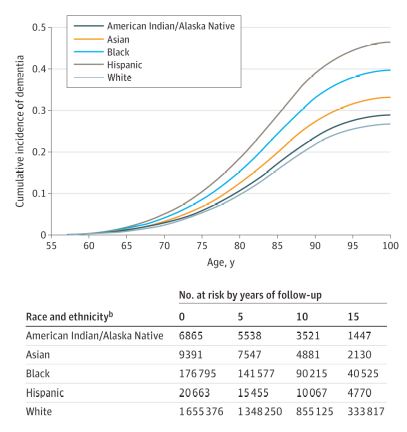

Of the total group, the researchers reported that 13% received a diagnosis of dementia over a mean follow-up of 10.1 years. Compared with white participants, the fully adjusted hazard ratios were 1.05 (95% CI, 0.98-1.13) for American Indian or Alaska Native participants, 1.20 (95% CI, 1.13-1.28) for Asian participants, 1.54 (95% CI, 1.51-1.57) for Black participants and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.82-2.02) for Hispanic participants.

Cumulative Incidence of Dementia by Racial and Ethnic Group Age is used as the timescale to indicate age at dementia diagnosis, and death is treated as a competing risk. Participants contributed follow-up data either until the age they died or developed dementia (whichever came first); patients who did not develop dementia or die continued to contribute to follow-up data until the age of their last medical encounter date. Dementia is defined using a comprehensive list of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and ICD-10 codes recommended by the Veterans Health Administration Dementia Steering Committee.

The table shows participant numbers at 0, 5, 10, and 15 years. The curves as plotted with competing risk models do not permit the creation of a more typical table of participants at risk.

Source: Jama Network

“Across most U.S. regions, age-adjusted dementia incidence rates were highest for Black and Hispanic participants, with rates similar among American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and white participants,” the researchers pointed out.

Background information in the article noted that past research examining racial and ethnic disparities in dementia incidence in the United States have consistently reported higher rates of dementia for Black adults. They added that, while less well studied, Hispanic older adults also have greater dementia incidence than white older adults, with less known about dementia incidence for American Indian or Alaska Native or for Asian individuals.

Racism and Risk Factors

“Structural and systemic factors including unequal access to health care, the health effects of racism, and differences in quality of care, as well as discrepancies in the prevalence of dementia risk factors (such as cardiovascular disease) play important roles in these differences,” the authors advised. “However, most prior studies of racial and ethnic differences in dementia incidence compared only 1 or 2 racial or ethnic groups, were limited to a specific geographical area, and often did not account for competing mortality.”

The issue is of special significance to the VHA because military-related risk factors such as traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder—as well as nonmilitary risk factors such as the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease—put veterans at significantly higher risk of dementia compared to other cohorts.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report dementia incidence for American Indian or Alaska Native older adults using a nationwide sample,” the authors noted. “Although American Indian or Alaska Native individuals make up only 1.7% of the United States population, they serve in the armed forces at higher rates than other racial and ethnic groups. Previous studies of dementia among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals have been small and geographically limited and have produced conflicting evidence, with some studies showing higher and some showing lower rates of dementia compared with White individuals. In this study, after accounting for demographics (including education) and the high rates of medical and psychiatric risk factors in the American Indian or Alaska Native group, there was no significant difference in dementia incidence compared with White participants.”

The authors also raised the question whether clinicians are more likely to diagnose dementia among Black participants or Hispanic participants “due to conscious or unconscious bias.” In addition, they suggested, nonwhite participants might be more likely to underperform on cognitive tests that are often used in dementia evaluations for reasons other than actual cognitive impairment, including test bias, English as a second language or lower educational attainment.

“Another possibility is that the racial and ethnic–based differences in dementia diagnosis reflect differences in susceptibility to dementia, influenced by socioeconomic and other structural factors, the health effects of racism, decreased cognitive reserve because of unequal access to educational opportunities or quality, and other social determinants of health,” they noted, adding, “Differences in dementia incidence could also be driven by discrepancies in risk factors or comorbid disease, such as cardiovascular risk factors and disease, which vary by race and ethnicity and are associated with socioeconomic and structural factors, and other risk factors that are more common among individuals receiving care at VHA facilities than patients receiving care at non-VHA facilities, such as PTSD.”

Researchers also pointed to significant racial and ethnic differences in education and many key medical and psychiatric comorbidities but advised that, when accounting statistically for those differences, differences were only slightly attenuated, suggesting that there may be other factors underlying the observed differences.

The authors also discussed the issue of access to healthcare, which is considered more equitable for patients enrolled in the VHA than for the general population. “This study showed differences in dementia incidence, despite this relatively equal access to care, which suggests that other mechanisms including early life circumstances may play a stronger role, or despite having access to care, there may be differences in quality of care,” they pointed out.

- Kornblith E, Bahorik A, Boscardin WJ, Xia F, Barnes DE, Yaffe K. Association of Race and Ethnicity With Incidence of Dementia Among Older Adults. JAMA. 2022;327(15):1488–1495. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3550