Did Access Come at Cost of Quality?

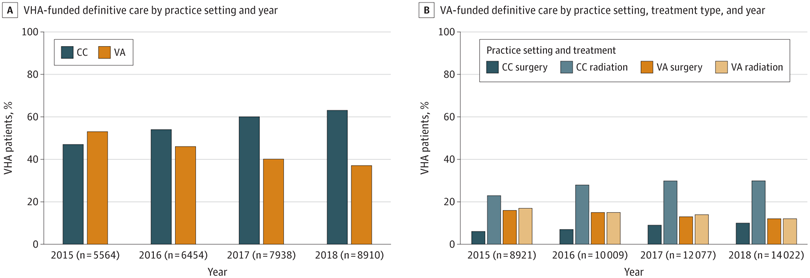

Click to Enlarge: CC indicates community care; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs; VHA, Veterans Health Administration. Source: JAMA Network Open

IOWA CITY, IA — Has greater use of community care for veterans with prostate cancer meant more overtreatment?

That was the question addressed in a new VA study looking at how the 2014 passage of the Veterans Choice Program (VCP) affected prostate cancer care delivery in veterans. The results were published in JAMA Network Open.1

Led by researchers from the VHA Office of Rural Health and the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, the cohort study of 45,029 veterans with newly diagnosed prostate cancer determined that, after VCP implementation, most patients elected to receive definitive treatment outside of the VHA system using purchased community care (CC).

Yet, the authors pointed out, “patients treated in the purchased CC setting had a higher likelihood of receiving definitive treatment for low-risk prostate cancer,” adding, “Findings of this study suggest that there was an increase in access to prostate cancer care associated with the VCP; however, this access may come at the cost of lower-quality care (overtreatment) for low-risk prostate cancer.”

That might be considered an unintended consequence of the Veterans Choice Program (VCP), which was implemented in 2014 to help veterans gain broader access to specialized care outside of VA healthcare facilities.

The study team set out to describe the prevalence and patterns in VCP-funded purchased CC among 45,029 veterans with newly diagnosed prostate cancer; their mean age was 67.1. The cohort study used VHA administrative data on veterans with prostate cancer—all of them regular VHA primary care users—diagnosed between Jan. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2018. Analyses were performed from March to July 2023.

Three factors were considered in ascertaining the location of where—VHA or purchased CC—treatment decisions were made: (1) location of the diagnostic biopsy, (2) location of most of the post diagnostic prostate-specific antigen laboratory testing, and (3) location of most of the post diagnostic urological care encounters.

Defined as the main outcome was receipt of definitive treatment and proportion of purchased CC by treatment type, such as radical prostatectomy [RP], radiotherapy [RT] or active surveillance. The distance to the nearest VHA tertiary-care facility was also taken in account.

The researchers evaluated quality care based on receipt of definitive treatment for Gleason grade group 1 prostate cancer, in which guidelines usually recommend low risk treatment because of limited benefits.

The results showed that 64.1% of the participants underwent definitive treatment. Overall, 56.8% of patients received definitive treatment from the purchased CC setting, representing 37.5% of all radical prostatectomy (RP) care and 66.7% of all radiotherapy (RT) care received during the study period. The study also noted that most patients who received active surveillance management (92.5%) remained within the VHA.

“Receipt of definitive treatment increased over the study period (from 5,830 patients in 2015 to 9,304 in 2018), with increased purchased CC for patients living farthest from VHA tertiary care facilities,” the authors pointed out. “The likelihood of receiving definitive treatment of Gleason grade group 1 prostate cancer was higher in the purchased CC setting (adjusted relative risk ratio, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.65-1.93).”

The researchers concluded that their study found that the percentage of veterans receiving definitive treatment in VCP-funded purchased CC settings “increased significantly over the study period. Increased access, however, may come at the cost of low care quality (overtreatment) for low-risk prostate cancer.”

Access to Specialized Care

Background information in the article recounted how the VCP was enacted in 2014 to formalize access to specialized care by offering to purchase community care (CC) for veterans who were living more than 40 miles away from the nearest VHA tertiary-care facility (or 60-minute travel time), were unable to obtain an appointment within 30 days, or had a VHA tertiary care facility that was lacking necessary condition-specific resources.

“While non–VHA-purchased CC has always been available to veterans on a case-by-case basis, the VCP appears to have boosted its popularity, with 1.3 million veterans being authorized for non-VHA care in 2014, which increased to nearly 2.3 million in 2021,” the study advised. “Purchased CC accounts for nearly 20% ($17.6 billion) of the total VHA clinical budget.”

The article went on to state that prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed solid organ tumor in male veterans, and about one-fourth of veterans with newly diagnosed prostate cancer live in rural areas that meet the VCP distance eligibility criteria.

“The VCP was enacted at a time when professional organizations began issuing guidelines that advised against aggressively treating clinically insignificant prostate cancer, as defined by early clinical stage, low Gleason score, and low prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level,” according to the researchers. “While these changes represent a step toward decreasing the risks of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, implementation of these changes in clinical practice has varied by region and health care system.”

Conservative management of clinically insignificant prostate cancer has increased significantly in the VHA; active surveillance and watchful waiting increased 2.3-fold—30% to 70%—from 2005 to 2015, there was a 2.3-fold increase (30% to 70%) in active surveillance and watchful-waiting rates for that type of prostate cancer, the study reported. The VHA’s increase was substantially higher than that observed in similar Medicare and community-based practice cohorts, it added.

“The historically strong relationships between VHA medical centers and academic medical centers as well as the lack of volume-based financial incentive for VHA clinicians may be factors in the relatively higher rate of adherence to evidence-based guidelines, particularly those against performing aggressive procedures,” the authors suggested. “However, it is unknown whether treatment patterns for veterans receiving prostate cancer urological care purchased with VCP funding differ from those for veterans receiving VHA care. Furthermore, although the VHA requires clinicians in the VCP to meet credentialing standards, the quality of VCP care is unknown and, to our knowledge, is not actively monitored by the VHA.”

The researchers said that, to their knowledge, the study is the first to argue that improved access with community care might come at the cost of lower quality for veterans. They pointed out that other surgical outcome studies have shown similar rates of complications for other high-volume purchased CC procedures, including cataract surgery and total knee arthroplasty, which might suggest similar surgical safety profiles.

“By focusing on the appropriateness of prostate cancer treatment as a quality measure and not on treatment outcomes, we highlighted that a potential weakness of the VCP may be the risk for overtreatment,” they wrote.

The study offered three explanations for the findings, noting that they have potential policy implications. Those are:

- The financial incentives of the VCP for clinicians outside the VHA must be considered. “Although accepting patients in the program requires the clinician to accept Medicare reimbursement rates, which may make VCP-funded surgical care less costly than surgery within the VHA, providing any intervention will nearly always be more financially rewarding to the community practice than providing no care,” the study noted.

- Fragmentation is inherent to purchased CC, the study argued, adding, “As has been shown previously, clinicians outside of the VHA system may view their relationship with the VHA patient as contractual, and both the patient and clinician may be motivated to undergo definitive treatment in the limited time allotted in the contract. Similarly, active surveillance, while recommended for most low-risk prostate cancer, can be a multiyear process with yearly biopsies and PSA testing. Additionally, discussions about not immediately treating a cancer can be complex, time-consuming, and confusing, and selecting active surveillance requires the patient to trust a physician’s recommendation that it is a beneficial and safe strategy.”

- VHA facilities, which are often affiliated with academic centers, tend to be more aware of evidence-based medicine and best-practice policies.

- Erickson BA, Hoffman RM, Wachsmuth J, Packiam VT, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS. Location and Types of Treatment for Prostate Cancer After the Veterans Choice Program Implementation. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2338326. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.38326