SEATTLE — Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of primary liver cancer, is the fastest-growing cause of cancer-related death in the United States. But a new study points out that the burden of the often deadly cancer is not spread equally.

“HCC-related disparities by race and ethnicity exist along the entire HCC care continuum, from early identification of cirrhosis to HCC-related mortality,” researchers from the VA Puget Sound Healthcare system, the University of Washington and their co-authors pointed out.

The report in Hepatology Communications noted that the cancer disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities in the United States.1

Worldwide, the most common risk factor for liver cancer is chronic (long-term) infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), according to the American Cancer Society. Because those infections lead to cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer is the most common carcinoma in many parts of the world.

HBV and HCV can spread from person to person through sharing contaminated needles, unprotected sex or childbirth.

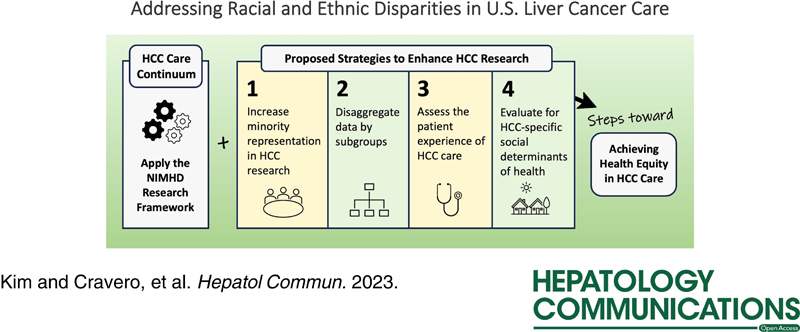

“A practical framework is needed to organize the complex patient, provider, health system and societal factors that drive these racial and ethnic disparities,” according to authors of the recent study. “In this narrative review, we adapted and applied the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Research Framework to the HCC care continuum, as a step toward better understanding and addressing existing HCC-related disparities.”

The researchers first summarized data on HCC-related disparities by race and ethnicity organized by the framework’s five domains—biological, behavioral, physical/built environment, sociocultural environment and healthcare system—and four levels of influence—individual, interpersonal, community and societal. They then offered strategies to guide future research initiatives toward promotion of health equity in HCC care.

The report cited U.S. population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data demonstrating that American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) people have the highest annual HCC incidence rate (15.7/100,000 persons), followed by Hispanic (13.5/100,000 persons), Asian Pacific Islanders (API) (12.6/100,000 persons), Black (11.0/100,000 persons) and white (7.1/100,000 persons) people.

“Between 2003 and 2011, Hispanic and Asian American people experienced a 35.8% increase and 5.5% decrease in HCC incidence, respectively,” the authors reported. “Between 1992 and 2018, AI/AN populations experienced a 4.3% annual increase in HCC incidence. By 2030, Hispanic and Black persons are projected to have the highest HCC incidence rates”.

The researchers urged that clinicians and others investigating the field might help mitigate further inequities and better address racial and ethnic disparities in HCC care by:

- Including increasing racial and ethnic minority representation,

- Collecting and reporting HCC-related data by racial and ethnic subgroups,

- Assessing the patient experience of HCC care by race and ethnicity, and

- Evaluating HCC-specific social determinants of health by race and ethnicity.

“These four priorities will help inform the development of future programs and interventions that are tailored to the unique experiences of each racial and ethnic group,” they wrote.

Multifactorial Disparities

The study suggested that disparities are multifactorial in origin and are linked to patient, provider and health-system factors. “Such factors may include downstream and midstream social determinants of health, which include but are not limited to individual health literacy, insurance coverage and neighborhood poverty,” the authors wrote. “In addition, more upstream factors, such as systemic racism and discriminatory U.S. policies (e.g., redlining to exclude Black Americans, immigrants, and working-class people from securing home or business mortgage loans) disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities, further exacerbating disparities in care.”

For example, the study pointed out that African Americans have high HCV prevalence compared to whites, while AI/AN have HBV genotype F1b or genotype C. API have high HBV prevalence, largely because of emigration from countries with high HBV endemicity. Hispanic and Latinos, according to the study, have HBV genotype F1b PNPLA3 gene polymorphism and might also be foreign born.

Minorities also have lower rates of referral to specialty clinics and, in some cases, have issues with English proficiency, according to the report. Those groups also are more likely to have lower rates of HCC detection when curative treatment, including hepatic resection, ablation or liver transplant, is possible. Minorities also might be less likely to receive cutting-edge care, such as with immunotherapy, or palliative care at the end of their lives, the authors pointed out.

“Evaluating HCC disparities by race and ethnicity has its limitations (e.g., race and ethnicity are social constructs, often self-reported, and do not fully account for the genetic and cultural diversity of a racial or ethnic group), but it can provide an opportunity for clinicians, researchers, and Tribal Health Organizations to advocate for interventions and policies that may address some of the existing inequities in liver cancer care,” the researchers wrote.

- Kim NJ, Cravero A, VoPham T, Vutien P, Carr R, Issaka RB, Johnston J, McMahon B, Mera J, Ioannou GN. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in US liver cancer care. Hepatol Commun. 2023 Jun 22;7(7):e00190. doi: 10.1097/HC9.0000000000000190. PMID: 37347221; PMCID: PMC10289716.